Denis Zogbi from Paumanok Inc. published article at TTI Market Eye with summary of passive components recent and historical capacitor industry acquisitions.

As we are fully involved in the final quarter of 2019, it’s worth noting that many passive capacitor companies have large amounts of cash on hand due to an exceptional 24 months of increased revenues. That cash has been earmarked for growing the business, either organically or through acquisition.

Many corporate directors in this sector have set their sights on growth through acquisition. Through acquisition, companies can achieve a much better return on investment over time compared to the ROI from specific product portfolios, financial instruments, property and/or equipment.

At the time of writing, it has been announced that Yageo Corporation has purchased KEMET Corporation in a $1.8 billion all-cash transaction (subject to certain approvals and set to close in 2020). This deal will create a company with $3 billion in revenue of which an estimated 65 percent will be from capacitors and dielectric-based materials.

This is the second time Yageo Corporation has demonstrated its prowess for timing acquisitions with an eye to the distant future, first purchasing the MLCC operations of Phycomp (Philips + Compass) in Taiwan and Holland, which paid massive dividends for Yageo shareholders in 2018 when a market vacuum created by Japanese vendors existing MLCC markets created a substantial return on investment for the company. It is also believed that KEMET’S suite of materials expertise in dielectrics will pay off dividends for Yageo Corporation in 2039.

The Acquisition Process: Picking the Target

Identifying the perfect acquisition for a company is crucial for a successful transaction. The process involves creating a wish list of potential acquisition candidates based upon the synergistic potential of the target: how acquiring the target extends the product offerings available to existing customers, or gives the acquirer access to new geographical sales regions or customers.

In the acquisition of KEMET, for example, Yageo gains access to many new automotive customers and vastly expands their presence in North America. This also gives Yageo access to KEMET’s massive customer base in defense electronics and dominant control over the tantalum capacitor and materials supply chain, including the invaluable ability to convert ore into powder.

Proper Timing

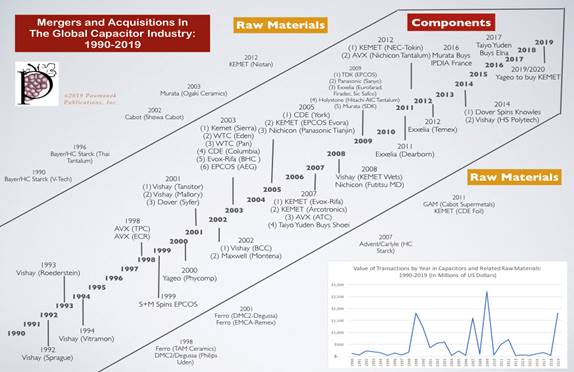

Market timing is also key in a successful acquisition strategy (see Chart in Figure 1). Most sellers and buyers know this and try to equally time the buying or selling of a business so as to maximize or minimize the amount of money involved. Of course, the seller wishes to exit when the market is at its peak while the buyer wishes to buy when the market is at a low point.

However, both sides generally understand that, given knowledge of the five-year cycle in high-tech, the best time to buy and the best time to sell is right before the market turns for the better. In this scenario, there is a certain level of compromise that inevitably leads to a successful transaction which benefits all involved.

Fig. 1: Mergers and Acquisitions in the Global Capacitor Industry, 1990-2019

Figure 2 – Cycle and Value of Transactions Impacting the Capacitor and Dielectric Materials Supply Chain, 1990-2019

Maximizing Return on Investment

A successful acquisition can lead to more than 100 percent return on investment in just three to five years in the passive components industry. Of course, a bad acquisition can lead to financial disaster for the acquirer, so both thought leadership and due diligence are required to set valuation and guarantee a good return.

In many instances, larger companies which have been built on acquisitions are much better suited to guarantee larger rates of return in acquisitions. However, financial institutions and trade companies that need new market access tend to pay more than those that are actively pursuing deals in the space.

Here are some ways to help maximize the rate of return on an acquisition:

Low-Cost Manufacturing Alternatives – One sure way to guarantee a good rate of return on an acquisition is to target a company in a high-cost manufacturing location, then move the new asset to an existing location with a much lower cost to produce. Of course, this strategy requires the company to already have a low-cost manufacturing location somewhere in the world. The other caveat is that the products produced at the target company cannot be so application-specific and value-added that the movement of the asset will result in substantial downtime.

Product Synergies – Targeting acquisitions with synergistic product lines accomplishes two goals. First, it gives the acquirer greater market share, which can be extremely beneficial if it gives the final entity market share in the top three suppliers either regionally, or better yet, globally. (This is important because many end-users of passive components simply wish to know who the top three suppliers are of any given product line). In this instance, the new acquisition is truly greater than the sum of the individual parts.

The other benefit of this approach is that it enables the acquirer to dispose of redundant personnel and limit the costs associated with sales, advertising and administration, thus increasing the profitability of the acquired asset. Combining administrative functions, sales, marketing and advertising through mergers and acquisitions has proven over time to be the most profitable method of growing a company in the passive component space.

Customer or Regional Access – Access to new customers is always a significant point in buying a company, especially if the asset is located in a world region where the acquirer has limited or no presence. This approach can be extremely attractive if the acquirer has complimentary component lines that they can push through to the new customer base.

Expanding the Product Portfolio – Another reason why companies target specific vendors for takeover is they have one or more complimentary, but non-competing, product lines that are attractive because they extend the offering of the existing product line. In passive components, for example, this would include accessing product lines created from different dielectric, resistive or inductive elements that increases the total product offering based upon capacitance, ohmic or nanohenrie value.

Or, by expanding the product portfolio, a target may have access to application specific or value-added component lines, instead of a traditional mass commercial product line-up. An expanded product portfolio is desirable because many end-users, especially electronic manufacturing services companies and distributors, like to work with vendors who are “one-stop shops” providing compartmentalized solutions.

The Valuation Process

What a buyer will pay and what a seller expects for their company are typically two distant numbers. Generally speaking, a buyer should not pay more than four times EBITDA and a seller should not sell for more than two times EBITDA. However, as of late in this industry, key deals – especially those favoring value-added components – have been at ten times EBITDA. An average of three years of EBITDA is typically used.

This figure can play an important role in the timing aspect. Many companies like to use EBITDA from the latest banner year to value their current companies, while buyers would prefer to use the EBITDAs from the worst years. (In my experience, this distance causes deals to lose traction.)

Once again, the willingness to compromise is key for successful transactions, and patience and persistence are key ingredients to all success. And still, companies tend to pay more if they can maximize their return on investment over time by obtaining one or more of the criteria listed above.

Also, financial institutions tend to pay more for an acquisition than a trade company, but in many instances this is due to the wish for the financial institution to make a return on investment in a short period of time (based on the cycle), either by selling to a trade company at a future date or by bolting other acquisitions together under one financial umbrella. Trade companies tend to pay less for acquisitions because they are more knowledgeable about markets and technologies, as well as the true potential for return on investment. Also, they are typically limited with respect to financial resources.

Methods of Payment – Generally speaking, cash is king in doing deals, but it is not unheard-of for a publicly traded company to use stock for a part or even for the entire transaction. Buyers will take stock depending on whose stock it is and, of course, depending on the timing in the cycle. Historical stock pricing is used as a benchmark, and if timed correctly the value of the stock could be worth much more over time then the company could ever have hoped to get in cash. Still, some large publicly-traded companies shy away from this approach if it may diminish shareholder value, so cash is typically the better way to get a deal done quickly and on time.

Closing the Deal – Another interesting aspect of the deal process is how quickly a company can close on an acquisition. Some potential acquirers have the tendency to analyze every aspect of the potential pitfalls of the deal and spend too much time on due diligence. In a bidding process this can be a deal breaker. Companies who have been built through acquisition understand this and typically avoid this mistake. On the other hand, some companies get blinded by getting the deal done and do not spend enough time on due diligence, which in turn can spell trouble for the acquirer.

Completing the Cycle: What Motivates Companies to Buy?

Paumanok Publications, Inc. has tracked monthly trade data on passive components for 30 years. During this time, specific patterns have been identified in the industry based upon consumption. The market usually is in check and behaves as expected, with small value growth on a year-over-year basis. This is punctuated by years of “reset” where shortages occur, prices adjust higher and the supply chain generates substantial amounts of cash very quickly. Immediately following this up-cycle and cash generation comes an increase in asset-based mergers and acquisitions.

Based on a detailed analysis of each of the acquisitions made in the capacitor and resistor segments over the past 30 years, we have come to the conclusion that the majority of acquisitions (67 percent) were made because they were an integral part of a grand strategy of the acquirer. This grand strategy either included the extension of a product portfolio to be a “one-stop shop” and to appear attractive to distributors; or, it involved the dominance of a specific segment of the market, with emphasis upon the value-added and application specific component segment.

Looking at the value of assets transferred, about 21 percent of acquisitions were based on the need for the acquirer to gain specific technology that they did not have and could not emulate. This need for technology typically involved high-capacitance ceramics, high CV/g tantalum powders, conductive polymer technology and thin film resistors. The final 12 percent of acquisitions we consider to be “opportunity-based,” whereby a vendor wanted to exit the market and an acquirer saw the opportunity to expand and acted on it.

Are There Patterns in the Timing of Acquisitions?

A close look at the myriad of transactions in the passive component market over the past 30 years reveals some interesting patterns:

- Vishay is the most active acquirer of companies in both capacitors and resistors, and is a pioneer in developing conglomerates by yoking like component groupings together in harmony. Part of the Vishay strategy, in fact, creates part of the pattern: if Vishay can identify an asset which it can make more profitable by having it come under the Vishay corporate umbrella through the combination of SGA, or by moving all or part of production to another part of the conglomerate in a low-cost region of the world, then that asset becomes a target for takeover.

- Companies are more likely to want to buy target acquisitions during times of great cash infusion into the market to reduce taxable income, but the target companies are less likely to sell at such times because they are too distracted in keeping up with orders rather than looking for a formulated and immediate exit strategy. Subsequently, the famines which usually follow feasts in the global passive component industry occur at the times when targeted vendors wish to exit and when acquirers actually commit to transactions.

- Regardless, transactions are continual, and it can be argued that since 1998 those assets have been changing hands on a frequent and ongoing basis.

- Acquisitions can be influenced by outside forces threatening the market, especially those involving disruptive technologies.

Global Acquisitions in Capacitors

The following section of this article describes the global acquisitions in the capacitor industry (as noted in Figure 1 above) and also the related raw materials being acquired.

The Tantalum Supply Chain – Our research for this MarketEYE article has revealed that the majority of transactions impacting the capacitor industry have been related to tantalum between 1990 and 2019. Tantalum has been the focal point of many transactions related to electronic components and raw materials. One fascinating fact: Fifty percent of all capacitor and material related transactions between 1990 and 2019 were related to the tantalum supply chain, according to our estimates.

- Interestingly enough, this process began with the acquisition of Sprague Capacitor by Vishay Intertechnology in 1992. At the time, Vishay’s strategy was to expand from their positioning in resistors to create a broad dielectric solution in capacitors as part of an attempt to be more attractive to distributors.

- This was preceded by a technology-based acquisition by HC Starck (a Bayer AG subsidiary at the time) of V-Tech, a Japanese producer of capacitor-grade tantalum metal powder.

- In 2001, Vishay decided to add to Sprague’s positioning in the value-added and application-specific tantalum capacitor market through the strategic acquisition of both Tansitor and NACC Mallory.

- In 2002, Cabot Corporation purchased a controlling interest in their Japanese joint venture with Showa-Denko Corporation (which can also be considered a technology-based acquisition because it increased Cabot’s capabilities to produce high CV/g capacitor grade powders).

- In 2005, KEMET Corporation purchased the tantalum division of EPCOS AG located in Evora, Portugal to increase its positioning in conductive polymer tantalum capacitors.

- This was followed in the same year by Nichicon Corporation, one of the world’s largest manufacturers of aluminum electrolytic capacitors, who purchased the tantalum division of Panasonic Industrial Corporation.

- In 2007, KEMET Corporation purchased the plastic film capacitor producer Arcotronics, which included the coveted Towcester UK tantalum wet capacitor operations.

- Also in 2007, Bayer AG sold its H.C. Starck operations (capacitor-grade tantalum metal powder and wire producer) to Advent and Carlyle (two financial concerns).

- In 2008, Vishay Intertechnology purchased the Towcester wet tantalum capacitor operations from KEMET Corporation, further enhancing the Vishay strategy of dominating the value-added and application specific tantalum capacitor markets worldwide.

- In 2009, Panasonic merged with Sanyo Corporation, which brought Panasonic back into the tantalum capacitor business that it had exited in 2005.

- Also in 2009, there was the creation of Exxelia in France, which includes Firadec as a founding company; this is France’s premier producer of tantalum capacitors.

- And again, in 2009 there was HolyStone’s purchase of Hitachi AIC’s tantalum capacitor line.

- In 2011, Global Advanced Metals purchased the Cabot Supermetals business, which included massive capacitor-grade tantalum powder production sites in the U.S. and Japan, under the control of the same company that owns the world’s largest tantalum ore resources in Australia (i.e. GAM , formerly Sons of Gwalia).

- In 2012, there was even more activity in tantalum with KEMET’S purchase of Niotan, a capacitor-grade tantalum metal powder producer in the USA. This was followed by KEMET’S purchase of the Tokin business of NEC Corporation in Japan, Asia’s largest producer of tantalum capacitors, and by AVX Corporation’s purchase of Nichicon Corporation’s tantalum capacitor operations (which previously had been owned by Panasonic and sold to Nichicon in 2005).

- In 2014, further consolidation in the tantalum supply chain resulted after Vishay announced the purchase of HolyStone’s Polytech Company, formerly the tantalum operation of Hitachi AIC.

- And in 2020, pending approval, Yageo will become the world’s largest tantalum capacitor manufacturer and materials processor through its acquisition of KEMET.

The Ceramic Supply Chain – Acquisitions impacting the ceramic capacitor supply chain accounted for an estimated 31 percent of all capacitor and related material acquisitions between 1990 and 2019, as follows:

- The first major acquisition in the ceramic capacitor supply chain during this time period was Vishay’s acquisition of Vitramon from Thomas & Betts in 1994. Vishay purchased Vitramon in an attempt to continue its strategy of being a “one-stop shop” in passive components and subsequently being more attractive to distributors. The purchase of Vitramon expanded the captive product offering of Vishay from tantalum and film into ceramic capacitors.

- This was followed in 1998 by Ferro Corporation’s purchase of TAM Ceramics from Cookson. The combination of Ferro’s existing Transelco facility with the acquired TAM Ceramics facility gave Ferro a significant command over the merchant market for ceramic dielectric materials.

- During the same year, DMC2 purchased the captive ceramic dielectric materials operations of Philips Electronics located in Uden, Holland. At the time, the Uden facility specialized in the production of ceramic dielectric materials for high-capacitance MLCC development. (Kudos in hindsight to DMC2 for seeing that high-capacitance MLCC was to be the next big thing in capacitors and related materials.)

- In 2000, there was the major purchase of the ceramic capacitor operations of Philips Electronics (known as Phycomp) by Yageo Corporation in Taiwan-ROC.

- In 2001, Ferro Corporation purchased DMC2 and their related Uden facility, and also purchased EMCA-Remex, a producer of metalization materials for passive components.

- Also in 2001, Dover Corporation, through its Novacap subsidiary, purchased Syfer of the UK, a specialty producer of value-added and application specific ceramic capacitors.

- In 2003, there were a series of acquisitions related to the ceramic capacitor industry. KEMET Corporation purchased the ceramic capacitor assets of Sierra/KD Corporation, which increased their presence in value-added and application specific ceramic capacitors.

- This was followed in China by Walsin Technology Corporation’s purchase of Eden Technology Corporation and Pan Overseas, both manufacturers of ceramic capacitors.

- Meanwhile, in Japan, Murata Manufacturing purchased Ogaki Ceramics, which expanded Murata’s technology base in low-temperature co-fired ceramic technology.

- In 2007, AVX Corporation purchased the publically traded American Technical Ceramics (ATC), which increased AVX’s presence and commanding market position in value-added and application specific ceramic capacitors.

- In 2012, Exxelia purchased Temex Ceramics from Tekelec in France and expended its value-added and application specific acquisition strategy into the ceramic dielectric realm.

- In 2014, Dover Corporation spun off its ceramic capacitor operations, including Novacap, Dielectric Labs and Syfer Technology into Knowles Corporation.

- In 2019, Yageo announced its purchase of KEMET Corporation and (pending approval) will become the third-largest MLCC manuafacturer in the world.

Plastic Film Supply Chain – Acquisitions involving the plastic film capacitor supply chain accounted for about 19 percent of cumulative capacitor asset value in transactions between 1990 and 2014:

- Transactions in the plastic film capacitor supply chain began with Vishay’s 1993 acquisition of the German film capacitor manufacturer, Roederstein.

- This was followed in 1998 by AVX’s purchase of Thomson Passive Components (TPC) which was largely a film capacitor house (both AC and DC).

- In 1999, Siemens + Matsushita Corporation spun out EPCOS, a major German manufacturer of plastic film capacitors (and many other types of components).

- In 2002, there were two major acquisitions involving plastic film capacitors: Vishay’s purchase of BCC and Maxwell’s purchase of Montena (Power Film).

- In 2005 there was the CDE purchase of York, which expanded CDE’s position in aluminum electrolytic capacitors into the power film capacitor business.

- In 2007, KEMET made two major purchases in the film capacitor space with the acquisition of Evox-Rifa in Europe and Arcotronics Italia SpA in Europe

- In 2011, Exxelia purchased Dearborn, a manufacturer of value-added and application-specific plastic film capacitors located in Florida.

- In 2019, Yageo announced the purchase of KEMET Corporation to became the second largest manuafacturer of plastic film capacitors in the world.

Aluminum Capacitor Supply Chain – Acquisitions in the aluminum electrolytic capacitor supply chain are few and far between, representing only 5 percent of all transactions in the capacitor segment between 1990 and 2019. (One major vendor noted that few transactions in aluminum capacitors actually take place because seldom does anything come up for sale.) Regardless, transactions of note include:

- In 2002, Vishay purchased BCC (which included a significant amount of aluminum capacitor revenues).

- This was followed in 2008 by Nichicon’s purchase of Fujtisu Media Devices to gain access to a larger market for conductive polymer aluminum capacitors.

- Murata’s purchase of Showa-Denko Capacitor in 2009 was also related to the acquisition of conductive polymer aluminum capacitor technology.

- This was followed by CDE’s purchase of the Philips Columbia SC aluminum capacitor operations in 2011.

- Also in 2011, KEMET’S purchase of the CDE foil operations (which CDE had previously purchased from Panasonic) located in Knoxville, TN.

- In 2017, Taiyo Yuden Corporation purchased Elna Corporation in a major transaction involving Elna and their production of aluminum electrolytic capacitors, with Elna having significant share in Japan’s electrolytic markets.

- And in 2019, Yageo purchased KEMET Corporation to became a minor supplier of large can aluminum electrolytric capacitors.