Researchers at Osaka University demonstrated a new technique for modifying the hydrogen concentration of resistors by applying an electrical voltage. The generated electric field drove the diffusion of hydrogen ions deeper into the perovskite rare-earth nickelate lattice, which led to a tunable “colossal” increase in electrical resistance. This research can lead to new gas sensors and electrically switchable smart materials.

Computer chips depend on the careful control of electrical signals through semiconductors. Conventionally, the conductivity of silicon chips is modified by intentionally “doping” them with impurity ions. However, this process is usually done once at the factory, and cannot be changed later. Thus, the ability to dynamically control the doping of materials would open the way for novel switches and potentially even entirely new kinds of computer circuits.

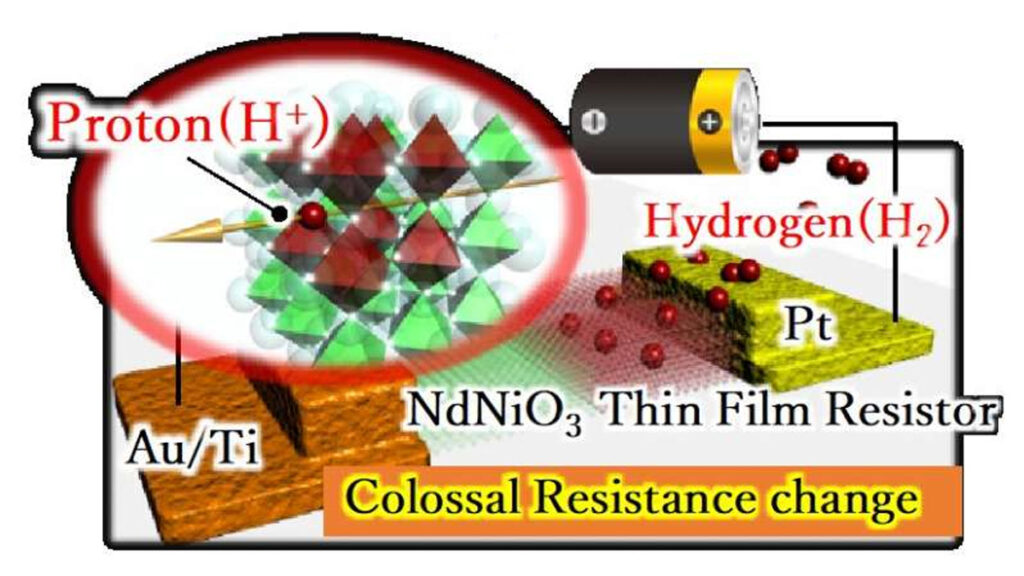

Now, scientists at Osaka University have created thin films of neodymium nickel oxide (NdNiO3) with an electrical resistance that can change dramatically by controlling the distribution of hydrogen ions (protons) in the film. The hydrogen was added in a process called “gas-phase annealing” in which the thin film, which has a perovskite crystal structure, was exposed to hydrogen gas in the presence of an electric field which caused the formation of hydrogen protons. This reaction was sped up by platinum electrodes, which act as catalysts.

Increasing the annealing temperature caused more protons to diffuse into the film. At room temperature, the resistance of the films doubled from the original value, but jumped by a factor of 30 at 200°C. “We call such a large increase in resistance ‘colossal’ because it is easily detected in electronic devices,” first author Umar Sidik explains.

In this way, the combination of electric field and gas-phase annealing at a desired temperature was shown to enable control of the diffusional doping, which led to electrically tunable colossal resistive devices. The crystal structures were confirmed using X-ray diffraction and optical microscopy. The change was visible because the hydrogen-doped region became optically transparent.

“In addition to the large resistance modulation, ion doping also has potential to reversibly change the structural and electronic properties of correlated materials via an electric field by manipulating the ion diffusion process into or out of a material,” senior author Azusa N. Hattori says. In fact, this can lead to the whole area of “iontronic” devices that rely on ion motion within a solid lattice to function.