source: Energy Harvesting Journal news

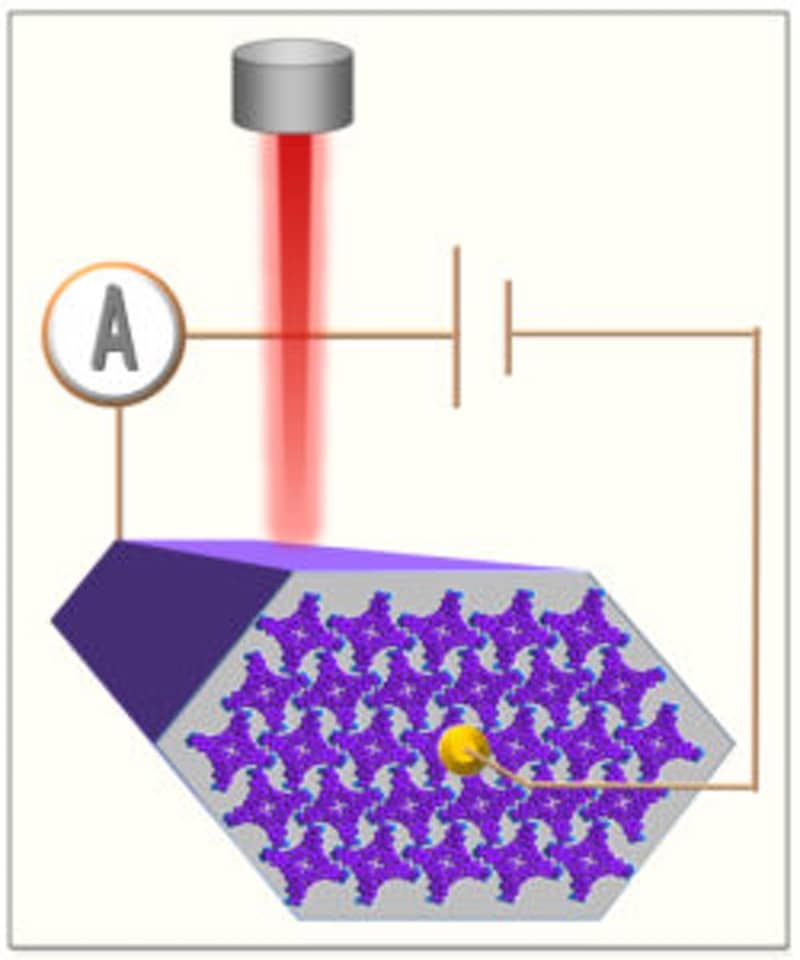

Washington State University chemists have created new materials that pave the way for the development of inexpensive solar cells. Their work has been recognized as one of the most influential studies published in the Journal of Materials Chemistry in 2016.

Professors Ursula Mazur and K.W. Hipps, postdoctoral researcher Bhaskar Chilukuri and graduate students Morteza Adinehnia and Bryan Borders grew chain-like arrangements of organic nanostructures in the laboratory and then used mathematical models to determine which arrangements were the best conductors of light and electricity.

Journal editors recognized the WSU study as an important step in the advancement of organic semiconductors that perform on par with metal- and silicon-based electronics. They included the work in a collection of 2016’s most influential research publications, or “Hot Papers.”

Growing affordable electronics “The organic semiconducting materials we are making have many advantages,” Mazur said. “Not only are they lightweight and flexible but they are also easy to transport and can be grown into almost any arrangement you can imagine. They could be used to make inexpensive solar cells and for many other alternative energy applications.”

The challenge of organic semiconductors is they don’t conduct electricity as well as their metal-based counterparts. Standard silicon-based semiconductors conduct electricity several times more efficiently than the best organic ones. But unlike their metal- and silicon-based counterparts, organic semiconductors are lightweight and can be grown inexpensively in the laboratory by mixing together common organic materials like porphyrins.

Improving organic conductivity

The WSU researchers found that by altering the reaction environment, they could control how porphyrin crystals assembled into conductive nanostructures. Like master chefs perfecting a new recipe, the researchers then used mathematical models to determine which nanocrystal concoctions might grow the most conductive materials.

“In the past, researchers have had a hard time figuring out how well electric current travels through organic nanostructures because they are very small,” Mazur said. “The mathematical models we created helped us figure this out.”

The WSU chemists’ research provides a systematic approach for fine-tuning the chemical formulations used to produce organic electronics. The scientists are now applying what they learned toward making more highly conductive materials. The work is in keeping with WSU’s Grand Challenges, a suite of research initiatives aimed at large societal issues. It is particularly relevant to the challenge of sustainable resources and its theme of meeting energy needs while protecting the environment.

Source and top image: Washington State University