Source: Electronics Specifier article

The case sizes of Multi-Layered Ceramic Capacitors (MLCC) available today are seemingly ever shrinking, which coupled with a long term reduction in manufacturing capacity for legacy commodity products and dramatically increasing manufacturer lead times is creating a supply headache for customers in Europe. In this update Adam Fletcher, Chairman of the Electronic Components Supply Network (ecsn) examines the current issues and suggests how they may be overcome.

Passive components (capacitors, resistors, ferrites, coils and inductors) are essential for almost all electronic circuitry, but the machinations of this sector of the electronic components market are rarely discussed in the media, probably because the passive component market is considered to be boringly established and ultra-stable.

Engineers, buyers and the wider electronics industry tend to focus their interest primarily on ‘exciting’ developments in microcontrollers and associated firmware and other technology that they can employ to differentiate their end equipment in their market. Passive components represent only a small proportion of the value in most Bills of Material (BOM) and here in the UK only represent approximately 12% of total electronic components sales by revenue.

Capacitor sales account for only 4% of sales by revenue of which half are sales of ceramic capacitors. These figures are slightly higher than the global average, reflecting the UK’s lower manufacturing volumes and our greater use of larger case-sized, more expensive MLCCs.

The quantity of Multi-Layered Ceramic Capacitors (MLCCs) manufactured is staggering, easily exceeding a trillion devices a year but potential threats to their availability of are nothing new. Industry analysts, trade associations, manufacturers and their authorised distributors have been warning about shortages for years.

The average quoted manufacturing lead time for all MLCCs has been over 12 weeks since 2013 but leapt up to 18 weeks in 2017 and this year (2018) MLCC lead times have further extended in leaps and bounds. Fletcher fears that this situation will get worse, especially for older legacy/commodity larger case size MLCCs and will probably reach a peak in mid-2019 before returning to more normal market conditions.

Why is this happening?

No passives manufacturing organisation has ‘ownership’ of legacy commodity MLCCs in the merchant market. They merely add their available product onto the market and accept the market price. This has led to fierce price competition for many years, which has precipitated several ‘boom and bust’ cycles. No surprise therefore that manufacturers have been reluctant to add new manufacturing capacity for legacy parts in the current growth cycle.

Instead passives manufacturers have invested heavily in research into improving the ceramic dielectric materials, electrolyte powders and pastes over the last twenty years which has dramatically reduced the physical size of the devices, whilst increasing their performance, at the same time making many small sequential improvements to their manufacturing processes to increase yields.

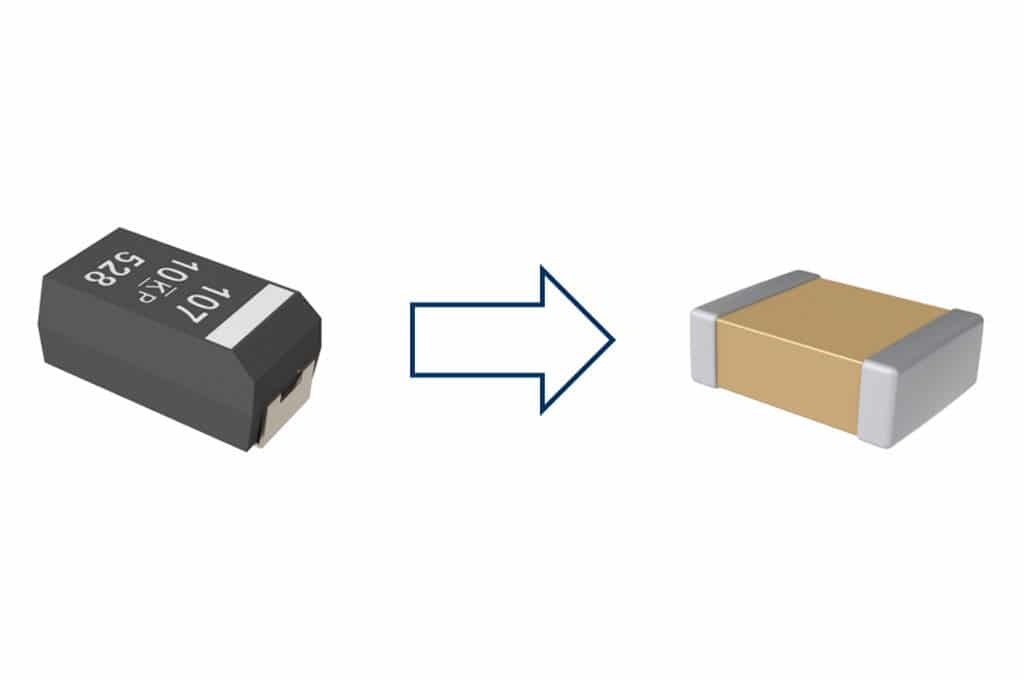

The industry leaders are today offering MLCCs with over 1,000 interposing layers, substantially increasing the capacitance of the devices and at the same time boosting stability and reliability. The improved price\performance ratio has enabled engineers to replace many tantalum and electrolytic capacitors with better performing lower priced MLCC devices, enabling the sector to grow at a rate significantly faster than other types of capacitors.

Demand drivers

Demand for MLCCs has been primarily driven by Cellular Mobile Phones, Automotive, Tablet PCs and LED/LCD TVs. Early generations of mobile phones used a mere 50 or so MLCCs but that has dramatically increased over the last 20 years. The iPhone X design employs more than 1,000 MLCCs while more modest (and affordable) modern smartphones have more than 600.

There has also been huge growth in the integration of electronics within the automotive sector. Many internal combustion engine vehicles today use more than 300 MLCCs in both ‘under the hood’ (engine management) applications and in the ‘passenger compartment‘, spanning essential instrumentation, infotainment systems and even seat controls. However, this is probably the very tip of the iceberg, the latest Tesla models of electric cars have over 10,000 MLCCs per vehicle!

Smaller case sizes

The drive to smaller physical MLCC sizes is a compelling economic argument: It takes the same volume of processed dielectric material to produce a single ‘1206’ case size MLCC as it does to produce 128 off ‘0402’ case size MLCCs. It is therefore obvious where manufacturers are concentrating their manufacturing capacity investment.

In 2018 there has been an intersection in the quantities of the two most commonly used MLCC case sizes. The almost 50% market share enjoyed by the ‘0402’ for many years is today declining and the format is being usurped by the ‘0201’ with a growing more than 40% market share. However, over the next five years the predominance of the ‘0201’ case size is likely to decline in favour of the ‘01005’, which already has 10% market share and is growing fast.

Further, forward thinking designers should already be considering the ‘008004’, a device that is taking off rapidly and is already outselling the ‘1206’, albeit that global demand for the 1206 is now small.

A bigger problem In the west?

Mobile phone companies are leading the drive to smaller MLCC case sizes. In addition to the relentless demand for ever thinner phones smaller devices are more suited to the highly automated PCB assembly lines today offered by their primarily Asia-Pac located manufacturing partners. Lower manufacturing volumes in the US and Europe reflect a different mix of end products, which primarily target the industrial, medical, aerospace and automotive markets.

Mobile phones are produced in extremely high volume but have a surprisingly short life cycle. Conversely, the products primarily manufactured in US and Europe are produced in low or moderate volumes so end products often enjoy a 10-15 year life cycle. In addition, the formal process to approve changes is slow and arduous, which is why the demand for commodity legacy MLCCs in Western markets has remained pretty constant.

However, over the next few months it will unfortunately be necessary for design engineers to redesign and possibly requalify the equipment their company produces. This won’t be too much of a problem if the equipment manufactured is approaching the end of its life cycle but could present something of a headache if the equipment is scheduled to remain in production for several more years.

At a minimum the largest MLCC case size they should specify for the redesign should be a ‘0201’ and to really guarantee availability in the longer term, a ‘01005’ would probably be a better choice. Engineers could opt to migrate away from their ‘1206’ case MLCC to other capacitor technologies but this might only be a short term solution as capacity constraints are looming in Tantalum capacitors too.

Conclusion

Not keeping an eye on what’s happening to availability in the passive components market means that organisations may be missing some important intelligence on what are considered ‘jelly bean’ parts. It is almost certain that doing nothing will inevitably result in some very expensive line stops for Western customers in 2019.

The best quality information on how to proceed and avoid this looming problem is invariably available from authorised distributors’ applications teams and Fletcher encourages all organisation to actively engage with their partners throughout their electronic components supply network to find the optimum solution.

featured image source: Kemet