SMD Chip Resistors allow a very large miniaturization. This in its turn means short conduction paths and good high frequency characteristics. Furthermore there are particular high frequency (HF) chips in thin film technique.

Key Takeaways

- SMD resistors enable miniaturization and high-frequency performance in electronic designs.

- Different types include thick film, thin film, and metal foil, each with specific applications and characteristics.

- Thick film resistors are cost-effective for general-purpose use, while thin film resistors cater to precision applications.

- Key considerations for selection include resistance, tolerance, power rating, and thermal performance.

- Proper layout and assembly practices enhance reliability and performance of SMD resistors.

Overview of SMD Chip Resistor Types

SMD resistor technology has diversified far beyond basic thick‑film chips, and choosing the right type is often more critical than simply picking an exact resistance value. The overview below summarizes the most common categories and their typical use cases.

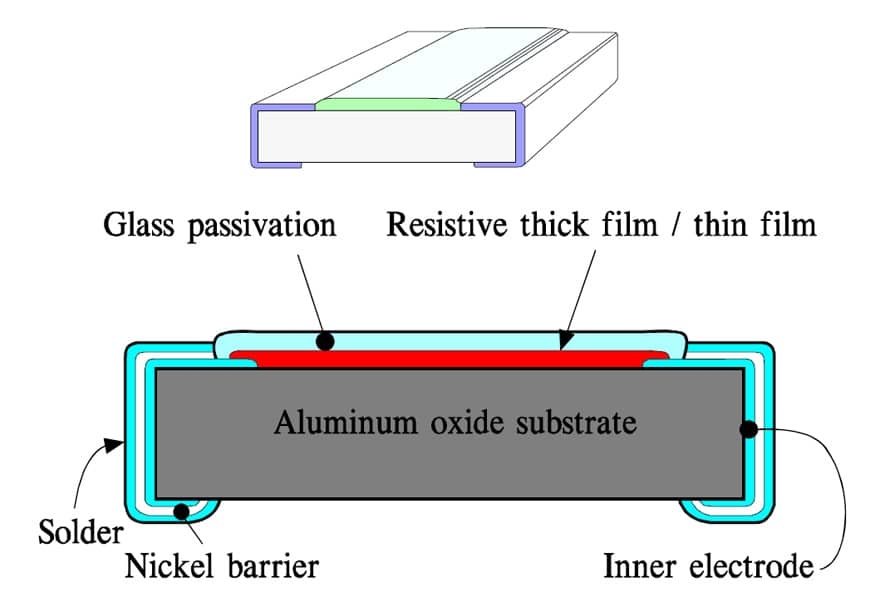

The predominant part of all chips are manufactured with thick film, but thin film chips are becoming more and more common. Also metal foil exists as SMD. The construction is like the one in Figure 1. Certain types have an organic protection in one or two layers on top of the glass passivation.

The substrates are screen printed either with a metal powder paste that is fired to a metal glaze / thick film. Or metal foils are glued on a substrate or metal films are vaporized or ion implanted on it.

The thick film is laser trimmed to the right resistance value by cutting a track in the long side of the film. Recent manufacturing improvements however begin making this laser trimming unnecessary. This approach without any trimming tracks will increase the pulse load capability by 2 to 3 times. The other films are designed to an inductance-reducing serpentine pattern according to Figure 2. and 3.

The metal foil pattern is etched chemically or patterned by means of an ion beam. The thin metal films are applied through a mask to the desired shape.

Thick Film Chip Resistors

Thick film chips are the standard choice for general‑purpose signal paths, pull‑ups and pull‑downs, bias networks and timing components. They offer a very wide resistance range from low ohmic values up to tens of megaohms, with good cost efficiency and robust manufacturing. Typical tolerances are 1–5% and TCR in the 50–200 ppm/°C range, which is sufficient for most non‑precision applications.

Thin Film Chip Resistors

Thin film resistors target precision analog and measurement applications where accuracy, low noise and stability are important. They typically provide tolerances from 0.1–1% and TCR as low as 10–25 ppm/°C, but with more limited power and resistance range compared to thick film. Thin film is widely used in instrumentation amplifiers, ADC/DAC interfaces, precision voltage dividers and feedback networks in high‑performance op‑amp circuits.

Metal Foil Chip Resistors

Metal foil resistors represent the high‑end class for ultra‑stable, low‑noise and very low TCR performance. They exhibit excellent long‑term drift and minimal resistance change with temperature, load and time, making them suitable for metrology, reference circuits and demanding laboratory instruments. Their drawback is higher cost and typically larger footprint compared with mainstream thick and thin film technologies.

Current Sense (Shunt) Chip Resistors

Current sense resistors are optimized to measure high currents with low power loss, usually in the milliohm range. They use specialized constructions such as metal strips or optimized thick‑film geometries and often offer Kelvin‑sense terminals for accurate low‑ohmic measurements. Typical applications are battery management, DC‑DC converters, motor drives and power distribution paths where precise current monitoring and efficiency are important.

Power Chip Resistors

Power chip resistors are designed to dissipate significantly higher power than standard chips in similar or only slightly larger footprints. This is achieved by optimized materials, larger terminations and improved thermal coupling to the PCB. They are used in power supplies, snubber networks, bleeder resistors and other locations where continuous or frequent high dissipation occurs.

Reverse‑Geometry and Wide‑Terminal Resistors

Reverse‑geometry parts swap length and width (for example 1225 instead of 2512) to improve thermal performance and lower inductance. Wide‑terminal designs couple heat more efficiently into the PCB and can provide better power handling and reduced ESL than standard shapes. These components are attractive in high‑power density designs and high‑frequency circuits, but they require careful footprint design and assembly process control.

The design benefits are in these fields:

- lower ESL = lower parasitic and higher frequency range

- better thermal conduction into PCB = higher power rating by 30-50%

- higher mechanical strength = higher vibration and flex stress robustness

- less thermal stress as differences in the coefficient of expansion between substrate and chip decreases in significance with shorter distances between terminations.

The downside of the design, considering the high manufacturing price is now almost identical, is a significantly more difficult PCB cleaning process in narrow and long gaps between the termination pads.

Jumpers and Zero‑Ohm Links

Zero‑ohm chip resistors act as configurable links, net jumpers or simple cross‑overs on densely routed boards. They are specified both by maximum resistance and maximum continuous current, which must be respected for reliable use. Designers often use them for configuration options, rework flexibility and to replace wire links in automated assembly.

Integrated and Buried Resistors

Resistor networks and arrays integrate multiple resistors into a single package, reducing placement count and improving matching. In addition, some PCB technologies support embedded resistive layers that implement buried resistors directly inside the board stack‑up. These approaches are attractive in high‑density, high‑volume products where space, performance and BoM optimization are critical.

Electrical Characteristics and Selection Criteria

Beyond resistance and package size, the main performance drivers for SMD chip resistors are tolerance, temperature coefficient, voltage and power rating, noise and long‑term stability. A structured view of these parameters helps to select the right device early in the design.

Resistance Range and Tolerance

Different technologies cover different resistance ranges and typical tolerance classes. Thick film offers the broadest range with standard tolerances of 1–5%, while thin film and foil focus on tighter tolerance but with somewhat restricted resistance span. For most digital biasing or pull‑up functions 1–5% is sufficient, whereas precision analog paths may require 0.1–0.5% parts or matched networks.

Temperature Coefficient of Resistance (TCR)

TCR expresses how much the resistance changes with temperature in ppm/°C. Common classes for thick film are around 100–200 ppm/°C, while thin film can reach 10–25 ppm/°C and foil even lower. When the operating temperature range is wide, TCR can dominate the overall error budget and justify the cost of a better technology.

Power Rating and Derating

The nominal power rating of an SMD resistor is specified at a reference ambient (often 70 °C) and then derated up to its maximum film temperature. In real applications, PCB layout, copper area, stacking of components and airflow have a strong influence on actual temperature rise. For long‑term reliability in industrial and automotive environments, it is common practice to use only 50–60% of the nominal power at maximum ambient.

Operating Voltage and Limiting Element Voltage

Each chip size has a specified maximum continuous working voltage and overload voltage. At high resistance values, the limiting element voltage may restrict safe operation even if the power rating appears sufficient. Designers must check both power and voltage limits, especially in mains‑related circuits, surge‑exposed nodes and high‑impedance dividers.

Noise and Stability

Resistor noise behavior differs between technologies, with thick film generally noisier than thin film and foil. Long‑term stability is also strongly technology‑dependent and can be affected by load, humidity and temperature cycling. Precision applications benefit from low‑noise, low‑drift technologies, while mass‑market digital circuits usually tolerate higher noise and drift.

Power Handling, Pulse and Surge Capability

Nominal power ratings and simple P=I2RP = I^{2}R checks are not sufficient where SMD resistors see pulses, inrush events or operation at elevated ambient temperatures. Both continuous and transient stresses must be considered together with the real thermal environment on the PCB.

Continuous Power and Thermal Design

Continuous dissipation is limited by the maximum permissible temperature of the resistive element and terminations. Standard data sheets define power ratings on reference test boards that may be more optimistic than dense real‑world layouts. Enlarging copper areas, using thermal vias and avoiding hotspots around the part significantly improves temperature margins.

Derating and Temperature Rise

Manufacturers provide derating curves that reduce allowable power above a given ambient temperature. For demanding applications, it is good practice to apply additional design derating on top of those curves to achieve the desired lifetime and reliability. Thermal simulations or simple temperature measurements on prototypes help to validate assumptions before release.

Pulse and Surge Ratings

Short pulses and surges are limited by instantaneous film temperature and current density rather than average power. Many series include dedicated pulse‑proof versions with optimized film geometry, terminations and substrates. For inrush, load dump, ESD or protection tasks, the designer should always consult pulse load and energy withstand graphs in the data sheet.

Influence of Laser Trimming

Laser trimming cuts in thick‑film paths can locally concentrate current and introduce hot spots. This reduces pulse handling capability compared with untrimmed or specially designed pulse‑resistant films. In highly pulsed applications, untrimmed values or special series specified for pulse operation are usually preferable.

High‑Frequency Behaviour and Parasitics

At RF and with very fast digital edges, SMD chip resistors behave as a combination of resistance, inductance and capacitance. Package geometry, pad layout and surrounding copper all influence this high‑frequency behavior.

Parasitic Elements (ESL and ESR)

Each chip resistor exhibits an equivalent series inductance (ESL) due to current paths through the terminations. Long, narrow terminations and large loop areas increase ESL and can limit performance at high frequencies. Reverse‑geometry and wide‑terminal parts reduce loop area and thus ESL, offering better behavior for high‑speed or RF signals.

Capacitive Coupling

Chip resistors also show parasitic capacitance to the ground plane and to neighboring tracks. This can be critical for very high‑value resistors, high‑impedance nodes and HF matching networks. Careful layout with controlled clearances and minimized overlapping copper under sensitive components helps to reduce these effects.

Layout Guidelines for High‑Frequency Use

- Keep connections short and minimize loop area around the resistor.

- Place components close to active devices and transitions.

- Use symmetric placement and identical packages in differential or matched networks.

When frequencies or edge rates become high enough that generic thick‑film parts no longer meet performance, dedicated RF chip resistors with specified S‑parameter behavior should be considered.

Typical Applications of SMD Chip Resistors

SMD chip resistors are used across virtually all electronic equipment, from low‑cost consumer products to high‑reliability automotive and industrial systems. Understanding the application context helps to choose the right technology, size and rating for each position in the circuit.

Signal Conditioning and Bias Networks

In analog and mixed‑signal designs, SMD resistors set gains, offsets and bias points in amplifiers, filters and sensor interfaces. Thin film types are often preferred where low noise, tight tolerance and good long‑term stability are required, for example in instrumentation amplifiers, ADC/DAC front‑ends and precision voltage dividers. For less demanding biasing or pull‑up functions, standard thick film chips usually offer sufficient accuracy at lower cost.

Digital Pull‑Ups, Pull‑Downs and Terminations

Digital I/O lines typically use SMD resistors as pull‑ups, pull‑downs and line terminations. The main requirements here are appropriate resistance, adequate voltage rating and sufficient power margin, while tolerance and TCR are often of secondary importance. Thick film resistors in standard chip sizes dominate this area thanks to their low cost and wide value range.

Power Management and Current Sensing

In power conversion and distribution, SMD resistors serve as current sense elements, inrush limiters, bleeders and snubbers. Dedicated current‑sense chips or shunt resistors with low resistance, Kelvin terminals and high pulse capability are used to measure battery, motor or converter currents accurately and efficiently. Power chip resistors and pulse‑proof series are chosen where high continuous dissipation or repetitive surge loading is expected, for example in start‑up circuits, RC snubbers or discharge paths.

RF, High‑Speed and Impedance Control

At RF and high data rates, chip resistors appear in matching networks, attenuators, terminations and damping elements in transmission lines. Here the parasitic inductance and capacitance of the package and layout become critical, so reverse‑geometry, wide‑terminal or dedicated RF resistor series are often used. Careful placement, short connections and symmetric layouts help maintain controlled impedance and signal integrity.

Automotive, Industrial and Harsh Environments

Automotive ECUs, industrial control units and other harsh‑environment systems place stringent demands on resistor robustness and reliability. Components must withstand wide temperature ranges, thermal cycling, vibration and in some cases sulfur‑rich atmospheres. Designers therefore often select AEC‑Q200‑qualified thick or thin film series, sulfur‑resistant terminations and conservative derating for power and voltage stress.

Reliability, Assembly and Layout Guidelines

Many practical failures involve solder joints, terminations or mechanical damage rather than pure resistive element defects. Assembly, PCB design and environmental conditions therefore play a central role in the reliability of SMD chip resistors.

It is important to remember that SMD components, more than others, are influenced by temperature changes, especially for the larger component. Thus, dimensions and mounting directions are most important. Further, short and wide bodies are preferable to long and thin ones, partly for strength reasons, partly because of the inductance and with that the frequency dependence will decrease. Still another reason is that differences in the coefficient of expansion between substrate and chip decreases in significance with shorter distances between terminations.

Typical Failure Mechanisms

Common failure mechanisms include solder joint fatigue from thermal cycling, PCB bending and vibration. Cracking of the ceramic body can occur due to mechanical stress during depanelization, handling or improper board support. In sulfur‑rich atmospheres, some thick‑film terminations are prone to corrosion, which can be mitigated by sulfur‑resistant series.

Failure modes

The weakest point of an SMD is the terminations and solder joints that break after sufficient temperature changes. Good components should stand at least 100 cycles between temperature limits. Applications like modern car electronics have forced the requirements up to some 1000…10 000 temperature cycles.

Except for failures resulting from open mode in connections and solder joints there always are failure modes typical for corresponding hole mount types.

Assembly and Footprint Recommendations

Footprints should follow recognized standards and manufacturer recommendations to ensure balanced solder fillets and avoid tombstoning. Oversized pads and excessive solder volumes can increase mechanical stress and the risk of cracking or voids. Solder stencil design (aperture size, thickness, paste type) must match the chosen package sizes and assembly process capability.

Component Orientation and Board Design

Component orientation can influence both thermal gradients and mechanical robustness. For high‑power resistors, it is often preferable to orient the long side across the main heat flow direction to spread temperature more evenly. For current‑sense parts, orientation that minimizes current path length and ensures symmetrical copper on both sides of the component improves measurement accuracy and thermal balance.

Board layout should avoid placing critical resistors in areas prone to bending, such as near slots, cut‑outs or connectors. Adding copper “heat‑spreaders” and thermal vias under high‑power parts reduces local temperature rise and improves lifetime.

Quick Layout Checklist

Before releasing a PCB with critical SMD resistors, check at least the following points:

- Power dissipation on each resistor under worst‑case conditions, including derating.

- Voltage across high‑value resistors vs limiting element voltage rating.

- Pad size, stencil design and symmetry to avoid tombstoning and cracking.

- Position relative to board edges, slots and mechanical stress points.

- Thermal environment, copper area and potential hotspots in the surrounding layout.

Conclusion

SMD chip resistors combine miniaturization, good high‑frequency behavior and automated assembly compatibility, making them the default choice for modern electronic designs. Their performance, however, depends strongly on the selected technology, package size, electrical rating and layout implementation.

By understanding the differences between thick, thin film and foil technologies, recognizing the impact of power, voltage and pulse ratings, and accounting for parasitics and assembly‑related reliability, designers can turn simple resistor choices into robust design decisions. A short application‑specific review of each critical resistor position in the schematic and PCB layout is usually enough to avoid most common failures and ensure predictable circuit behavior over the full lifetime of the product.

FAQ: SMD Chip Resistors

SMD chip resistors are surface-mount resistive components designed for automated assembly that enable miniaturization, short current paths and good high-frequency performance in modern electronic circuits.

The main SMD resistor types are thick film, thin film, metal foil, current sense (shunt), power chip, reverse-geometry or wide-terminal parts, jumpers, and integrated or buried resistor networks.

Thick film resistors are best for cost-sensitive, general-purpose functions such as pull-ups, pull-downs and bias networks, while thin film resistors are preferred in precision analog, measurement and low-noise applications.

Selection should consider resistance value, tolerance, TCR, power rating, limiting element voltage, pulse and surge capability, noise and long-term stability, as well as the thermal and mechanical conditions on the PCB.

Power rating is limited by the maximum allowable temperature of the resistive film and terminations, which depends on chip size, PCB copper area, airflow and derating above the reference ambient temperature.

Reverse-geometry and wide-terminal resistors reduce parasitic inductance, improve thermal coupling into the PCB and increase mechanical robustness, which benefits high-frequency, high-power-density and high-vibration applications.

t high frequencies SMD resistors exhibit parasitic inductance and capacitance, so package geometry, pad layout and surrounding copper strongly influence their impedance and suitability for RF and fast digital signals.

Typical failures include cracked solder joints from thermal cycling, ceramic body cracks from PCB bending or handling, and sulfur-induced corrosion of terminations in harsh environments.

Automotive ECUs, industrial control, power management and other harsh-environment designs often use AEC‑Q200-qualified or sulfur-resistant SMD resistors combined with conservative derating for voltage and power.

Using proper footprints, balanced pads, suitable stencil design, good component orientation, generous copper for heat spreading and avoiding flex zones under critical resistors significantly improves reliability.

How to select SMD chip resistors for reliable electronic designs

- Identify the function of each resistor in the circuit

Review the schematic and classify each SMD resistor as a signal path element, bias or pull-up/pull-down, current sense, snubber, bleeder, termination, or RF/high-speed component.

- Choose an appropriate resistor technology

Use thick film for general-purpose and digital functions, thin film or foil for precision and low-noise analog paths, dedicated current-sense chips for high currents, and RF-optimized or reverse-geometry types for high-frequency applications.

- Define resistance, tolerance and TCR requirements

Set the nominal resistance from circuit calculations, then assign suitable tolerance and TCR ranges based on accuracy needs and operating temperature span; use tighter values for measurement and reference circuits.

- Check power dissipation and apply derating

Calculate worst-case power dissipation for each resistor, compare it with the datasheet power rating for the chosen package and then apply additional design derating, typically using no more than 50–60% of nominal rating at maximum ambient.

- Verify voltage, pulse and surge limits

Ensure that the maximum steady-state voltage across each resistor is below its limiting element voltage and that any pulses, surges or inrush events stay within the specified pulse load and energy withstand capabilities.

- Account for parasitics in high-frequency or fast-switching circuits

For RF, high-speed digital and sensitive analog nodes, consider the package ESL and stray capacitance; select suitable geometries, keep connections short and use symmetric layouts or dedicated RF resistor series when needed.

- Design footprints and layout for reliability

Follow recommended land patterns, stencil designs and pad symmetry, avoid placing high-stress resistors near board edges or slots, and use adequate copper and thermal vias to manage temperature and mechanical stress.

- Review critical resistors before release

Before finalizing the design, systematically check high-power, high-voltage, precision and safety-related SMD resistors against all electrical, thermal and mechanical criteria to ensure sufficient margins and reliability.