source: Datacenter journal article

written by Ulrich Brandt May 17, 2017

Although flash-memory devices, or solid-state drives (SSDs), are more robust than hard-disk drives (HDDs), data loss can nonetheless occur with SSDs in the event of a power failure. Thus, when you use SSDs as boot media or to store critical data for industrial applications, you need data-storage devices that reliably preserve data as fully as possible in the event of a sudden voltage drop.

The risk of power-failure-induced data loss in SSDs can be minimized in a number of ways. For example, the recently introduced 2.5″ SATA 6Gb/s SSD from Swissbit employs state-of-the-art technology with three interrelated protection levels.

But first let’s consider various scenarios. When a controlled SSD shutdown occurs, the ATA “standby immediate” command alerts the controller, thus enabling it to write all data in the buffer to nonvolatile NAND cells. In the event of a sudden voltage drop, if the host fails to transmit the “standby immediate” command to the controller, all unwritten information will be lost, resulting in corrupted files. Thus, the first protection level must replace the missing “pre-warning” from the host.

Level 1: Voltage-Drop Detection

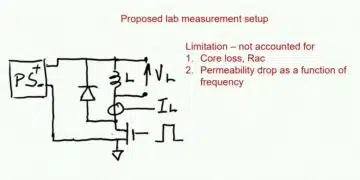

By monitoring the operating voltage, the SSD controller can detect a voltage drop if a power failure occurs. The controller’s firmware can trigger two measures on the basis of various threshold values: shut down all operations and issue a flash-write-protect (FWP) signal. If the first threshold value is reached, communication with the host is disabled, but the process of writing data to the SSD continues. If the second threshold value is reached, writing is disabled to prevent saved-data corruption as a result of partial flash-page programming.

An SSD normally takes upwards of three milliseconds to complete the writing process. For 5-volt devices, all commands to the SSD are blocked at 4 volts, and the FWP signal is sent at 2.4 volts. For 3.3-volt devices, the threshold values for voltage drops are 2.8 and 2.4 volts. The speed at which the voltage drops depends on the host and may or may not be slow enough to allow for an “orderly retreat.” If there’s not enough time—which often occurs with 3.3 volt devices, as their threshold values differ only slightly from one another—a firmware mechanism kicks in to reset partially programmed sectors to the prior values when the device restarts. Although data is still lost in such a case, data corruption caused by interrupted writing processes is avoided.

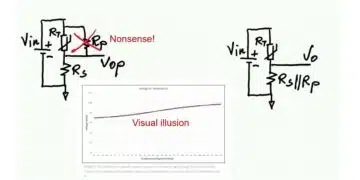

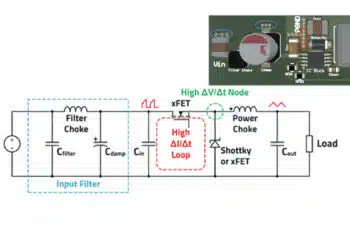

Level 2: Voltage Headroom

The second power-failure mechanism relates to voltage drops. As a rule, host- and flash-voltage curves are parallel to each other. The task here is to gain sufficient time to enable the SSD voltage-drop curve to flatten out. The solution is to integrate capacitors into the SSD power supply. On detecting the first threshold value, the controller disables host operations and at the same time discharges the capacitors to provide sufficient power to complete the writing processes. This type of power-failure protection is available in high-end server SSDs and industrial SSDs, such as the Swissbit X-60 and X-600 series.

A capacitor bank on an SSD PCB: the capacitors are lined up beside each other and ready to provide energy (along the right edge).

A capacitor bank on an SSD PCB: the capacitors are lined up beside each other and ready to provide energy (along the right edge).

Level 3: Complete Data Backup

High-end SSDs use DRAM to enhance performance and reduce the write amplification factor (WAF). The levels of the power-failure mechanism described above leave DRAM data unprotected. If this data needs to be reliably written to flash memories during a power failure (a mechanism referred to as data hardening), more-sophisticated circuitry and a larger capacitor power reserve is needed.

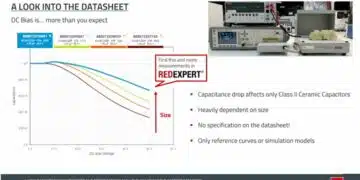

Manufacturers first must determine which capacitors are most suitable. If energy-storage capacity is the sole consideration, supercapacitors are the best solution, as they can store sufficient energy and deliver it if a voltage drop occurs. Hence, they are widely used for IT applications. But for SSDs that serve industrial applications or other exacting scenarios outside the controlled conditions of a data center, factors other than capacitor energy capacity come into play.

Because supercapacitors are “wet,”—that is, they contain a liquid electrolyte—they swell up and can destroy not only themselves but also adjacent components when subjected to high temperatures and voltage spikes. In response, two design approaches are helpful. First, the SSD can provide reserve power for DRAM data hardening via a bank of capacitors connected in parallel, rather than using supercapacitors. This solution, in keeping with the principle of N+1 redundancy, provides more than enough headroom in the event of a power failure. Second, polymer tantalum capacitors containing dry electrolyte create an outstanding and durable module that can withstand temperatures ranging from –55°C to +105°C.

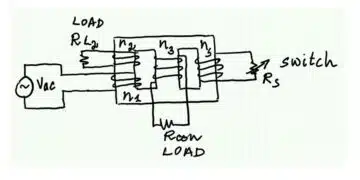

In the event of a voltage drop, this power-manager chip switches to the capacitors and generates a volatile-data “hardening” command.

In the event of a voltage drop, this power-manager chip switches to the capacitors and generates a volatile-data “hardening” command.

Power-Failure Circuitry

The bank of highly durable capacitors can be integrated into a special power-failure circuit, whose power-manager chip controls the power supply. Under normal operating conditions, this chip receives the power generated by the host, powers the SSD and at the same time charges the bank of capacitors to a higher voltage. If a voltage drop is detected, the power-manager chip switches the power supply from the host to the capacitors. At the same time, it generates a power-failure signal that triggers the controller’s data-hardening sequence. On completion of the SSD writing process, a “harden done” signal is generated, allowing for a controlled shutdown of the SSD voltage supply.

Conclusion

Apart from the state-of-the-art data-loss-protection mechanisms provided by high-end industrial SSDs in the event of a power failure, these devices offer additional features that differentiate them from server- or even consumer-grade SSDs. These features include a more robust casing and high-quality contacts. Another important feature of storage solutions for embedded applications is their longevity. This characteristic means not only availability or deliverability of the SSDs for many years, removing the need to requalify new product releases—a great investment protection—but also endurance, which is longevity from a technical standpoint. This characteristic is attributable to many measures that prevent premature aging, such as lower WAF and overprovisioning.