source: Energy Harvesting Journal news

Supercapacitors promise recharging of phones and other devices in seconds and minutes as opposed to hours for batteries. But current technologies are not usually flexible, have insufficient capacities, and for many their performance quickly degrades with charging cycles. Researchers at Queen Mary University of London (QMUL) and the University of Cambridge have found a way to improve all three problems in one stroke.

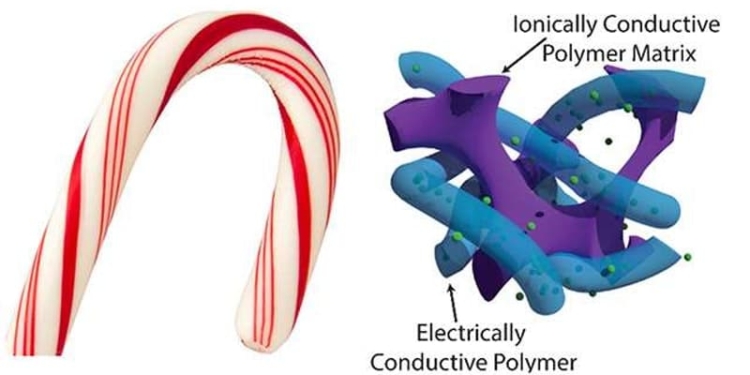

Their prototyped polymer electrode, which resembles a candy cane usually hung on a Christmas tree, achieves energy storage close to the theoretical limit, but also demonstrates flexibility and resilience to charge/discharge cycling. The technique could be applied to many types of materials for supercapacitors and enable fast charging of mobile phones, smart clothes and implantable devices.

The research was published in ACS Energy Letters. Pseudocapacitance is a property of polymer and composite supercapacitors that allows ions to enter inside the material and thus pack much more charge than carbon ones that mostly store the charge as concentrated ions (in the so-called double layer) near the surface. The problem with polymer supercapacitors, however, is that the ions necessary for these chemical reactions can only access the top few nanometers below the material surface, leaving the rest of the electrode as dead weight. Growing polymers as nano-structures is one way to increase the amount of accessible material near the surface, but this can be expensive, hard to scale up, and often results in poor mechanical stability.

The researchers, however, have developed a way to interweave nanostructures within a bulk material, thereby achieving the benefits of conventional nanostructuring without using complex synthesis methods or sacrificing material toughness.

Project leader, Stoyan Smoukov, explained: “Our supercapacitors can store a lot of charge very quickly, because the thin active material (the conductive polymer) is always in contact with a second polymer which contains ions, just like the red thin regions of a candy cane are always in close proximity to the white parts. But this is on a much smaller scale. This interpenetrating structure enables the material to bend more easily, as well as swell and shrink without cracking, leading to greater longevity. This one method is like killing not just two, but three birds with one stone.”

The Smoukov group had previously pioneered a combinatorial route to multifunctionality using interpenetrating polymer networks (IPN) in which each component would have its own function, rather than using trial-and-error chemistry to fit all functions in one molecule. This time they applied the method to energy storage, specifically supercapacitors, because of the known problem of poor material utilization deep beneath the electrode surface.

This interpenetration technique drastically increases the material’s surface area, or more accurately the interfacial area between the different polymer components. Interpenetration also happens to solve two other major problems in supercapacitors. It brings flexibility and toughness because the interfaces stop growth of any cracks that may form in the material. It also allows the thin regions to swell and shrink repeatedly without developing large stresses, so they are electrochemically resistant and maintain their performance over many charging cycles.

The researchers are currently rationally designing and evaluating a range of materials that can be adapted into the interpenetrating polymer system for even better supercapacitors. In an upcoming review, accepted for publication in the journal Sustainable Energy and Fuels, they overview the different techniques people have used to improve the multiple parameters required for novel supercapacitors. Such devices could be made in soft and flexible freestanding films, which could power electronics embedded in smart clothing, wearable and implantable devices, and soft robotics. The developers hope to make their contribution to provide ubiquitous power for the emerging Internet of Things (IoT) devices, which is still a significant challenge ahead.

Source and top image: Queen Mary University of London