The use of air conditioners and electric fans using evaporative cooling techniques today already accounts for about a fifth of the total electricity in buildings around the world – or 10% of all global electricity consumption. In addition the coolant are not completely green friendly. Scientists are evaluating other technologies that may bring better energy efficiency. One of the direction is electrocaloric (EC) cooling. Certain EC materials change temperature under an applied electric field. Applied voltage basically raises or lowers the entropy of the material. Ceramic capacitors show promise as EC components.

Recently, a group of scientists from Xerox Parc and Murata Manufacturing in Japan described an EC cooler employing lead, scandium, tantalum (PST) multilayer ceramic capacitors (MLCCs) as the working elements. A 10.8 MV/m field changes the MLCC temperature by 2.5°C at room temperature. Moreover, the researchers say their cooling scheme, which is now just a lab demo, can use capacitors fabricated in a conventional manufacturing process and can be scaled up to do real work. All in all, they think that scalable materials, together with mechanical simplicity and modular design, can ultimately lead to a system whose size, efficiency, and cost can compete with that of vapor compression A/C.

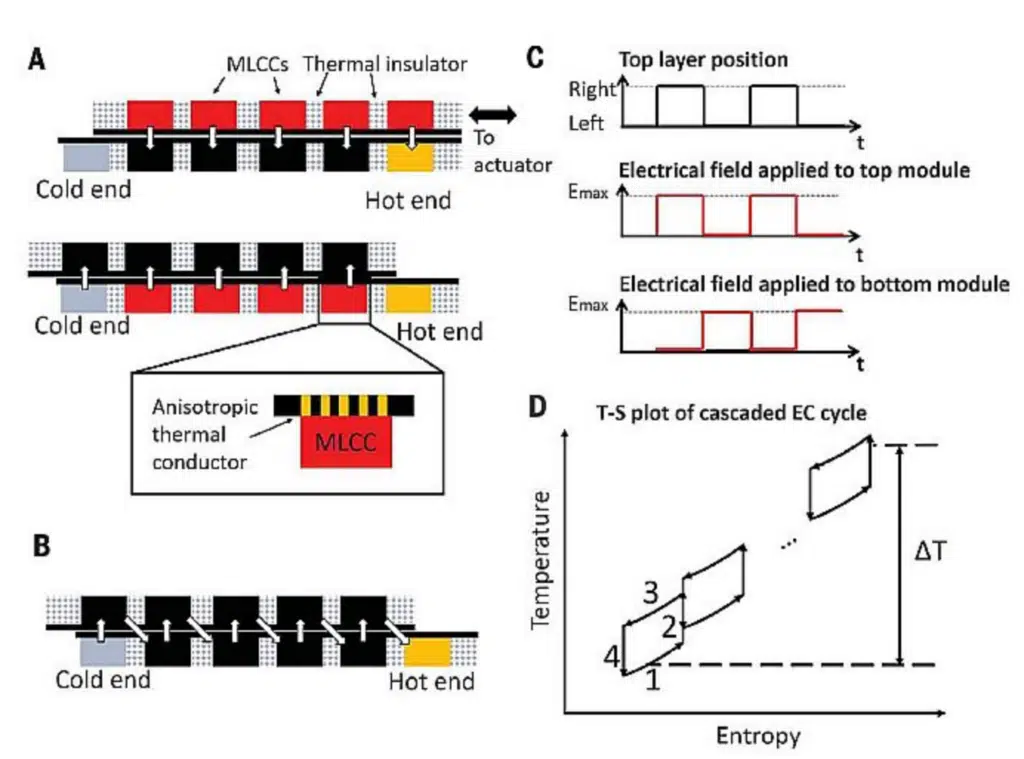

The device invented by the research team isn’t fully solid state. It physically moves the capacitors back and forth between hot and cold regions to effect cooling. Specifically, their system includes a pair of stacked modules, each containing EC MLCCs separated by thermal insulating materials. The modules are thermally coupled such that heat can transfer from one capacitor to the next. A mechanism moves the stacked modules laterally relative to one another while an electric field is switched on and off synchronously. The effect is to generate a temperature lift between the two ends of the device that exceeds the MLCC temperature change.

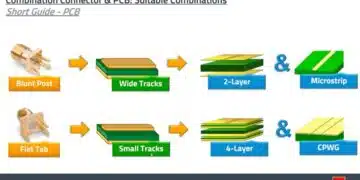

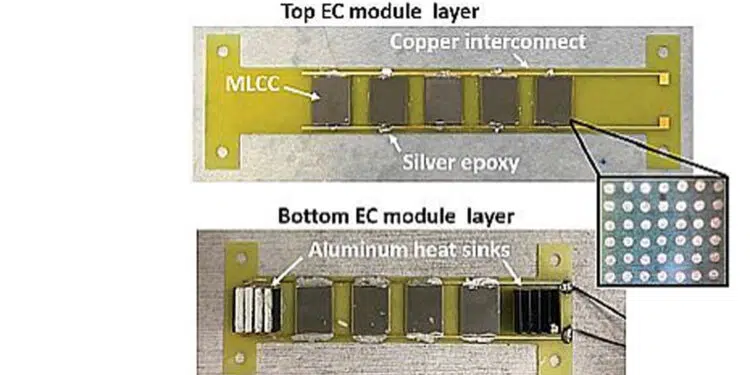

Also key to the design is the use of plates that enhance heat exchange between their layers but are good thermal insulators in the lateral direction. There is nothing exotic about their construction. They are basically glass-reinforced epoxy (FR-4) laminates and copper made via a standard commercial PCB process. In the regions of the plate where the MLCCs attach, plated-copper through-vias serve as thermal shunts for high through-plane thermal conductivity.

The MLCCs are assembled onto the plates to form the top and bottom EC modules containing five and four MLCCs, respectively. The bottom module has an aluminum plate-fin heat sink at each end to facilitate temperature stability. The modules sit in a 3D-printed VeroClear housing filled with polyurethane foam insulation. Besides providing structural support, the housing also minimizes heat leakage. A miniature fan at one end pushes air across the hot-end heat sink.

The top housing connects to a spring-returned single-acting linear solenoid actuator with about a half-inch of stroke. In operation, energizing the actuator draws the top module toward the actuator. When the voltage returns to zero, the solenoid relaxes and a spring returns it to its original position. The EC module housing provides vertical pressure through a set of wheels to keep good thermal contact between the two modules. Control software synchronizes the movement of the top module layer with the application of electric fields to the EC capacitors.

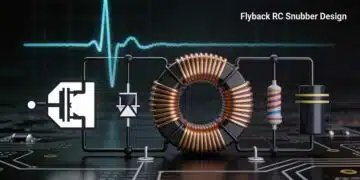

The MLCCs operate via a Brayton cycle, with two zero-voltage and two equal-entropy stages. The scheme uses a 400-V polarizing voltage (equivalent to ~10.5-MV/m electric field) and a 0.2-Hz switching frequency (5-sec period) with about a 50% duty cycle. There are heat sinks at both ends of the device. Over the course of the experiments, heat sink temperature on the hot end rises, while the temperature at the cold end changes in discrete steps as the heater power varies.

The cooling power seen in this small demonstration device is only on the order of hundreds of milliwatts per square centimeter. A more interesting question concerns its COP. Researchers say the EC system COP is a function of the heat collected from the cold side of the device, the additional electrical work associated with charging and discharging the EC capacitor, and the amount of electrical energy recovered each cycle. There’s also mechanical and electrical work required to move the reciprocating system, but that was so small that researchers figured they could safely ignore it. Factoring in all these parameters, they calculated a COP for the experimental setup that is about equal to that of existing Peltier devices.

Given all the possible improvements, researchers estimate EC-powered A/C using existing PST capacitor material might eventually hit COPs of about 56.4%, making their system competitive with vapor compression cooling.