Building out manufacturing capacity is one answer to the ongoing electronic components supply chain shortages, but it’s not the only answer. As semiconductor companies like Intel, GlobalFoundries and Samsung announce plans to build new sites or expand existing ones to add more capacity they are sending the message that they will do whatever they can to address the chip shortage and growing customer demand, but ultimately other business practices within the supply chain also will need to evolve, according to Anand Nambiar, global head of semiconductor materials for EMD Electronics, a business of Germany’s Merck KGaA.

“These announcements by the giants are commitments to create space,” he said. “Essentially, the new fabs are white space, and equipment and materials are needed to fill that white space. So the question becomes, ‘How do you fill this white space?’ It will take the supply chain time to catch up.”

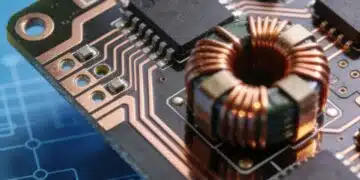

The chip shortage isn’t just a chip shortage. As other industry players have noted, it is also a shortage of both raw and integrated materials necessary for the manufacturing process. At the same time, the supply chain won’t get a chance to come up for air anytime soon, as fresh demand for all kinds of chips is increasing.

“All of these market segments that need chips–AI, 5G smartphones, data center servers, sensors, autonomous driving and others–they’re all growing at a rapid rate,” Nambiar said.

These trends are also going to generate more data, which means a growing requirement for more data analysis and development of insights based on the data, all of which means chips will need to be more powerful and more capable, with an increasing likelihood that more data analysis will happen on-chip or on-device. Right now, there is collectively still very little data analysis being done across all industries–different research sources put the figure in the low-to-mid single digits percentage-wise. If that percentage grows even a little, it could represent a doubling of the amount of analysis being done now, which could translate to an explosion in the need for chips with AI capabilities.

“All of these technology drivers are happening at the same time to create much more market demand, and that has been compounded by the fact of the supply shortage to create the more significant demand/supply disruption,” Nambiar said

Due to the wide range of factors in play to create this perfect storm of disruption, constraints in different parts of the semiconductor supply chain are likely to continue to pop up for years to come, he added.

The shortage combined with ever-broadening demand are the reasons “why companies are building so much more capacity, but for the next decade there are going to be ups and downs with market corrections and changes in pricing,” Nambiar said. “There will be a stabilizing effect from improvements in capacity and logistics, but there will also be sustained demand.”

Rethinking materials practices

This “new normal” means that chip companies will need to start to rethink how they acquire and work with the materials they need.

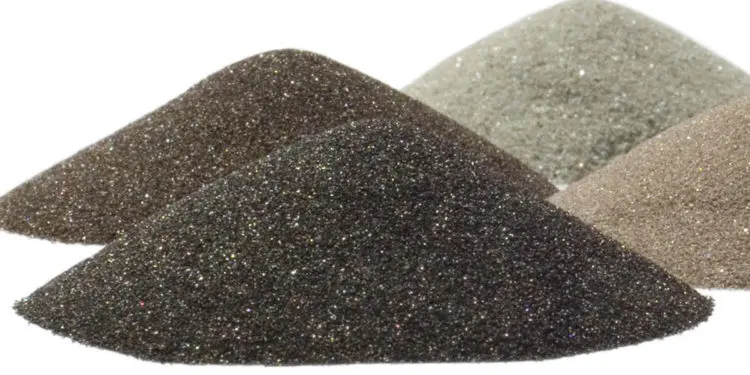

The demand/supply disruption has exposed the weakness of modern global-scale supply chains. For one thing, supply chains have become extremely complex, with too many moving parts for any one company to adequately control. Also, some manufacturing processes or supply sources for some materials have become so concentrated in individual countries (most tungsten traditionally come out of China, for example) that when problems arise in these locations, the supply chain can crash.

That could drive more companies to try to localize their sourcing to some degree to mitigate some of the blips that might occur in a more distributed chain, a practice companies and governments around the world are starting to buy into.

“Regarding the geopolitical aspects, there definitely is a nationalistic drive to build more capacity and ecosystem support in countries that are feeling left out of the chain,” Nambiar said. “But they need to do this smartly and focus on a strategy to localize their supply chain where this is possible. It’s important that materials and supplies are locally present for the new capacity being built [by chip companies].”

Living in a material world

Beyond localization, chip companies might also need to create longer-term strategies to acquire more raw materials and seek more integrated and packaged materials where they can to offset delays of these materials coming out of certain suppliers or countries.

“Two to three decades ago, fewer than 10 elements were used in chip processes,” Nambiar said. “Now, 50 to 70 of the elements on the periodic table are used, with even more under scrutiny. The next decade is going to be the decade of materials.”

But along with the exigent supply chain challenges, the broader range of materials being used means that the ability to integrate and package these materials to streamline the manufacturing process is increasingly critical.

“Materials are an opportunity for us to solve complex problems,” Nambiar said. “What happens today is that the chip customer works with many different materials suppliers, and the onus is on that customer to integrate everything.

“Think about how this market is evolving,” Nambiar said. “Google has started to drive chip design. Some companies want to own the entire value chain, others want to farm everything out, but they all need hardware. Facebook is doing AR and they need both display and semiconductor hardware competency to make that work. Amazon, Microsoft, Google — they all have hardware roadmaps. These companies are emerging to drive how semiconductor processes will work in the future.”