Researchers from UK and EU explore possibilities of manufacturing devices from pure mycelium or mycelial composites, a paper has been published in arXiv.

Fungal electronics is a family of living electronic devices made of mycelium bound composites or pure mycelium. Fungal electronic devices are capable of changing their impedance and generating spikes of electrical potential in response to external control parameters. Fungal electronics can be embedded into fungal materials and wearables or used as stand alone sensing and computing devices.

Flexible electronic devices have many designs. Typical designs include thin-film pressure sensors and transistors embedded in materials such as polymers and multilayered graphene. Hybrid electrodes can be printed to provide applications for piezoresistive pressure sensing or electromyographic recording, and other designs include devices with intrinsically conductive polymer-filled channels. Components that give flexible devices the ability to power themselves have been investigated in recent years.

Whilst typical flexible electronic devices have superior mechanical and electrical properties, they lack the ability to repair themselves or grow. Possessing these properties would be hugely advantageous to flexible electronic devices, helping to develop applications for fields such as “living” architecture, self-growing soft robots, and the development of smart materials. To overcome these issues, components based on biological organisms have been explored.

To explore the potential of flexible, smart electronics with self-repair and growth properties, the team behind the research in arXiv have investigated the development of various fungal electronic devices their application. The research includes explorations of fungal memristors, electronic oscillators, sensors that can detect pressure, chemical, and optical changes, and electrical analog computers.

Fungal Memristors

Memristors are resistors that possess a memory capability. In a memristor, the resistance is dependent on the past signal waveform of the current across it. A state-dependent Ohm’s law governs the function of a memristor. A memristor can be used to provide functionalities that are not possible with standard resistors, capacitors, or inductors. Another term for a memristors is a Resistive Switching Device and they contain two or three terminals.

In the research focused on using P. ostractus fruit bodies to create fungal memristors. Ideally, a memristor will have a crossing point at 0V. By attaching electrodes to the fruit bodies, a signal was recorded at this voltage, demonstrating that fungal bodies could generate a current. Thus, it was concluded that fungal bodies could be used as potential memristors.

Fungal Oscillators

In an oscillator, direct current is converted into an alternating current. To investigate the potential of fungal oscillators, the team carried out a series of experiments by applying a direct voltage to fungal substrates of P. ostractus and measuring the output voltage. The results of these experiments demonstrated clear voltage spikes using the mycelial-bound composite. It was concluded that fungi could be used in biological circuit designs as very low-frequency electronic oscillators.

Fungal Pressure Sensors

The research used blocks of substrate colonized with G. resinaceum. A 16 kg weight was rested on the blocks of the substrate with electrodes attaches to measure the fungal composite’s electrical activity when exposed to pressure.

The recorded electrical spikes demonstrated that the fungal composite could detect when the cast-iron weight was rested on it and when it was taken off, and the team concluded that fungal composite materials could be used as components in organic-based pressure sensors and in fungal building materials.

Fungal Photosensors

By using sheets of G. resinaceum skin, the research demonstrated the possibility of using mycelial composites in photosensors. The response to illumination in the fungi caused a raise in baseline potential, and the response did not subside until the illumination was ceased. The research concluded that the fungi displayed a change in electrical potential in response to illumination, facilitating their potential use as actuators and logical circuits with optical inputs.

Fungal Chemical Sensors

Hemp colonized with P. ostractus mycelium was used to test the response of fungal composites to chemical stimuli. The composites responded to these stimuli by increasing their frequency of electrical potential spiking. Whilst the research identified that this showed enormous potential, it pointed out that research is needed into calibrating these materials.

Mycelial Analog Computing

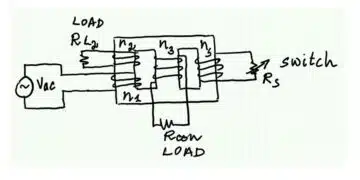

The research used Aspergillus niger fungal strains to investigate using fungi as components in electrical analog computers. It was found that mycelium-bound composites could implement a range of Boolean circuits, demonstrating their potential for hybrid and biological analog computing.

Potential Applications

Researchers propose a potential practical implementation of the electronic properties of fungi would be in sensorial and computing circuits embedded into mycelium bound composites. For example, an approach of exploiting reservoir computing for sensing, where the information about the environment is encoded in the state of the reservoir memristive computing medium, can be employed to prototype sensing-memritive devices from living fungi.

A very low frequency of fungal electronic oscillators does not preclude us from considering inclusion of the oscillators in fully living or hybrid analog circuits embedded into fungal architectures and future specialised circuits and processors made from living fungi functionalised with nanoparticles, as have been illustrated in prototypes of hybrid electronic devices with slime mould.

Electrical resistance of living substrates is used to identify their morphological and physiological state. Examples include determination of states of organs, detection of decaying wood in living trees, estimation of root vigour, the study of freeze-thaw injuries of plants, as well as classification of breast tissue.

Reference

Adamatzky, A et al. (2021) Fungal electronics [online] axriv.org. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2111.11231