With the current rapid growth rates of all critical materials, there is speculation regarding an increase in the production of tantalum as a by-product of hard-rock lithium projects. Project Blue predicts that hard-rock LCT lithium projects will account for 60% of the new projects coming online by 2033 to meet the demand for lithium-ion batteries.

Tantalum, classified as a ‘conflict mineral’, is one of the metals known as the ‘3TG’ (tungsten, tin, and gold) and is primarily produced in Central Africa. Its primary use lies in high-end tantalum capacitors and sputtering targets for semiconductors, making its demand closely tied to integrated circuit boards and electronic applications. Tantalum’s thermal stability allows for the creation of small capacitors that can fit within mobile phones and other portable electronic devices. Given that semiconductors require a significant number of materials as dopants or thin film layers to protect their vulnerable conducting wires, tantalum is used to coat these chips, providing anti-corrosion properties and safeguarding them from chemical degradation.

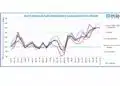

The majority of tantalum is recovered as a by-product of tin mining, particularly tin extracted in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The market for tantalum in Central Africa is opaque, especially when it comes to the African upstream, as DRC tantalum finds its way into the market through various routes, notably via neighboring Rwanda and to a lesser extent, Burundi. Project Blue data shows that Central Africa is a significant swing producer of tantalum. When the market experiences a deficit, resulting in higher prices, additional tantalum supply from Africa floods the market.

The recent spike in prices was driven by the increased demand for portable electronics during the COVID-19 pandemic. High prices stimulated a supply response, resulting in oversupply in 2022. The market has remained in surplus in 2023, with Central Africa’s output remaining high for a second consecutive year. The primary destination for Central African tantalum is China, where it is converted into metal and utilized in the domestic semiconductor and capacitor industries. The United States, the second-largest producer of tantalum metal, sources a significant portion of its stock from recycled material, with up to 50% of the world’s tantalum scrap and waste material being recycled in the USA. In addition to recycling, the USA also imports tantalum from Australia, where the USA-based company Global Advanced Metals (GAM) recovers tantalum concentrates from LCT pegmatites at the Greenbushes and Wodgina Operations.

Tantalum is an incompatible element that is often found in liquid form within late-stage melts of igneous rocks and in relatively small ore volumes. LCT-type pegmatites, a specific type of rock, are enriched in lithium-caesium-tantalum and usually contain a proportional increase in both lithium and tantalum. The Greenbushes operation in Australia is the largest producer of tantalum mined from hard rock lithium mines. Despite initially being mined for its tin content, the focus shifted to lithium due to the surge in demand. GAM holds the mining rights to the tantalum resources at Wodgina and Greenbushes, benefiting from the extractive costs associated with the lithium operation. GAM is currently the sole tantalum producer in Australia and also purchases tantalum concentrate from other lithium operations. With its vertical integration, the company exports its products to refining facilities in the USA. Additionally, certain pegmatites also contain tin as a co-mineralized phase, though the Ta:Li ratio is generally higher than the Ta:Sn ratio. As a result, tantalum as a tin by-product has historically been the main source of tantalum, given the larger volume extracted for the tin market. With the current growth rates of lithium among critical materials, the question arises whether tantalum production will increase as a by-product of hard-rock lithium projects.

Governments have recognized the critical role of tantalum in their technology supply chains. Developed countries such as the USA and China have begun imposing restrictions on tantalum, with geopolitics playing an increasing role in the tantalum landscape beyond its classification as a 3TG mineral. For instance, the USA has banned the export of high-end chip-making equipment to China, restricted the import of tantalum metal, and encouraged domestic chip production. In response, China has placed bans on gallium and germanium products. As a result, further strain on the tantalum supply chain can be expected in the short term. Recent reports have shed light on how chip manufacturers managed to produce a 7-nanometer chip for Huawei’s new Mate 60 Pro, despite export restrictions imposed by the Biden administration in October 2022 to curb advancements in China’s semiconductor industry. The effectiveness of export controls on chipmaking equipment is challenging to enforce due to the limited capacity to verify the actual applications of the equipment.

It is noteworthy that the demand for portable electronics is projected to continue growing in 2024, even though silicon wafer shipments for semiconductor applications have experienced a significant decline from their peak during the COVID-19 pandemic. Major producers like Apple have increased their buy orders, particularly for 3-nanometer chips to be incorporated into upcoming iPhone 16 models.

The demand for tantalum is expected to rise due to its use in capacitors and semiconductors, driven by the growth of portable electronics and high-end chips required for applications like AI learning. According to Project Blue data, additional supply beyond the current known resources, including hard-rock lithium and other existing miners, will be required by the late 2020s to meet the growing demand. In the near term, we anticipate a surge in Central African artisanal and small-scale mining production around 2026/2027 to compensate for the projected deficit and high prices once the stocks have been depleted. Alternatively, high exports from Central Africa may continue for a third consecutive year, as the closure of the Myanmar-China border could lead to additional tin production from Africa to accommodate the tin market, consequently generating a by-product of tantalum.

Project Blue predicts that hard-rock LCT lithium projects will account for 60% of the new projects coming online by 2033 to meet the demand for lithium-ion batteries. While tantalum resources and estimates have not been extensively defined for LCT mines and projects outside of Australia, several LCT deposits within Australia are already considered in the base case supply outlook for tantalum. The Australian LCT assets account for only 34.5% of the forecasted lithium supply. This implies the potential for significant volumes of additional tantalum to be produced from LCT mines and projects worldwide, provided there is a similar geological association of tantalum and lithium as observed in Australian LCT deposits. Consequently, if all LCT lithium miners are able to extract tantalum, there is potential to replace as much as two-thirds of Central African tantalum supply in the short term, which could contribute to minimizing the association of tantalum with 3TG conflict minerals and enhance its ESG (environmental, social, and governance) credentials. An interesting development to watch in this field is the announcement by Resource Capital Funds to sell GAM. Existing participants in the lithium market will ascertain whether tantalum can serve as a positive economic by-product and differentiate projects aiming to join the lithium-ion battery supply chain. Alternatively, tantalum may remain a disregarded waste product, thereby missing out on potential improved ESG credentials. Regardless, significant increases in tantalum production will be required to support high-tech applications, many of which are crucial for the energy transition.