This guide summarizes design‑relevant aspects of thin film, metal film and metal foil resistors, with emphasis on selection, derating and PCB implementation.

Key Takeaways

- Thin Film Resistor offers precision and stability, making them ideal for applications requiring low noise and long-term reliability.

- These resistors are typically made from a homogeneous metallic alloy and are used in circuits like precision amplifiers and RC networks.

- Metal foil resistors provide the highest precision, while standard metal film covers mainstream needs, and thick film is the low-cost option.

- Careful PCB layout and derating are crucial to optimize performance and stability in demanding applications.

- Selecting between thin and thick film resistors involves balancing cost, tolerance, and application requirements.

Role of Thin Film and Metal Film Resistors in Circuits

Thin/metal film resistors are used whenever you need precision and stable resistance over time, temperature and voltage. Typical roles include:

- Gain‑setting in precision amplifiers, ADC/DAC reference paths, instrumentation bridges and sensor interfaces.

- Timing and RC filter networks where drift, noise and non‑linearity of thick film is not acceptable.

- Low‑noise feedback and load resistors in audio and RF front‑ends.

- Precision current sense (in the low‑ohmic thin film domain) where inductance must be minimized and pulse stress is moderate.

Metal foil resistors serve the highest‑precision niche (metrology, reference circuits), while standard metal film covers mainstream precision needs; thick film remains the low‑cost workhorse where precision is not critical.

Construction and Manufacturing Principles

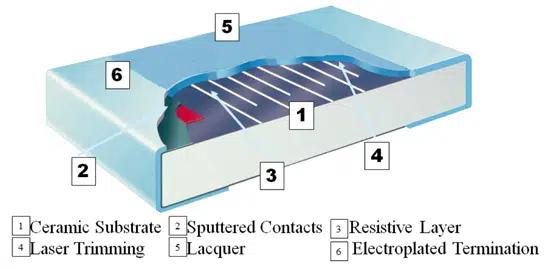

Thin/metal film resistors use a homogeneous metallic alloy film (typically Nichrome or TaN) deposited on a ceramic substrate and trimmed to value.

- Substrate: usually 96% alumina or similar ceramic, rod (axial/MELF) or flat chip.

- Film deposition: sputtering or evaporation of alloys such as CrNi or Ta₂N, with additives (Al, Si, Ti) to tune TCR and stability.

- Trimming: helical laser cut on cylindrical bodies; laser or photo‑etched patterns on chips.

- Protection: multilayer lacquer or epoxy molding; hermetic styles for high‑reliability.

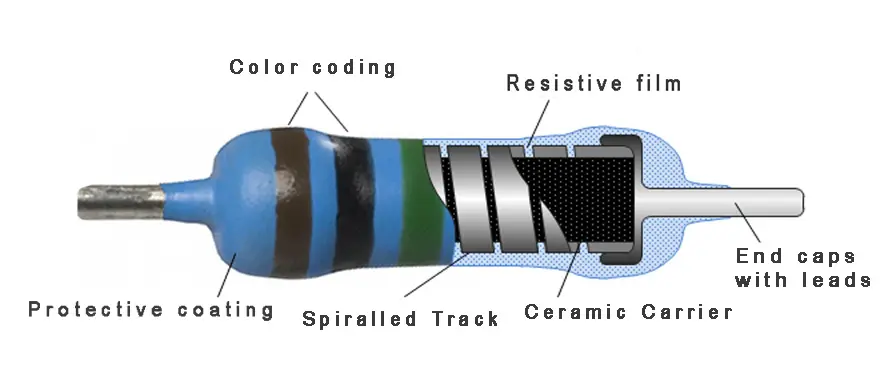

Helical trimming creates stray capacitance between turns and some inductance, so axial metal film parts behave slightly inductive at low values and capacitive at high values.

Film resistors are built either on cylindrical rods or on planar substrates. Usually the material in the rods and substrates is ceramic in the state of aluminum oxide (alumina), but glass may occur. Hollow cores exist but are more and more abandoned when sizes are becoming smaller. This design suffers also from drawbacks: the construction is more fragile and the heat dissipation is poorer than that of a solid core.

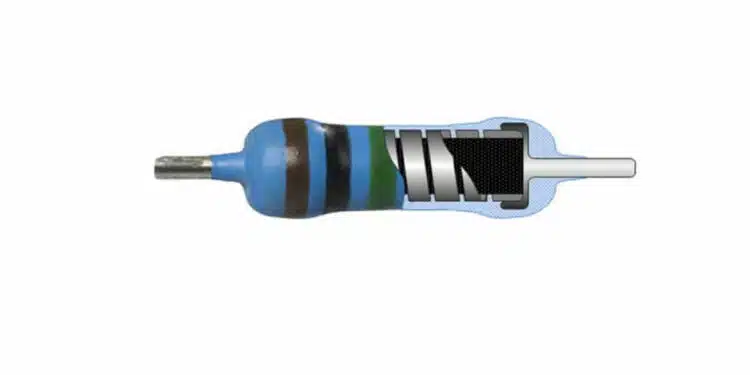

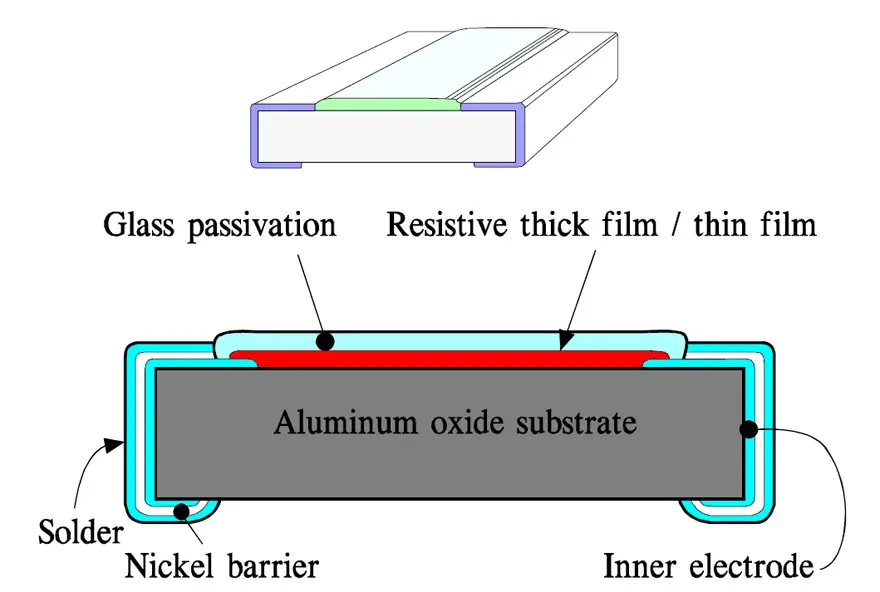

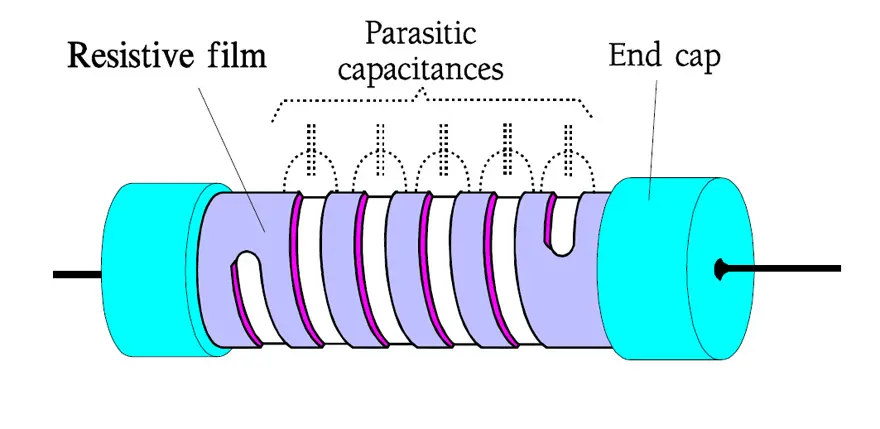

A typical through hole film resistor construction is shown in Figure 1.

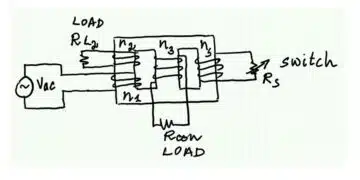

The film of the cylindrical rods thus are cut in a helical track to a long path, usually with a laser. A more stylized sketch is shown in Figure 2. The pitch of the helix track can be varied in order to increase the resistance of the film. For thick films an increase of up to 150 times, for carbon and metal films up to 1000 times or even more.

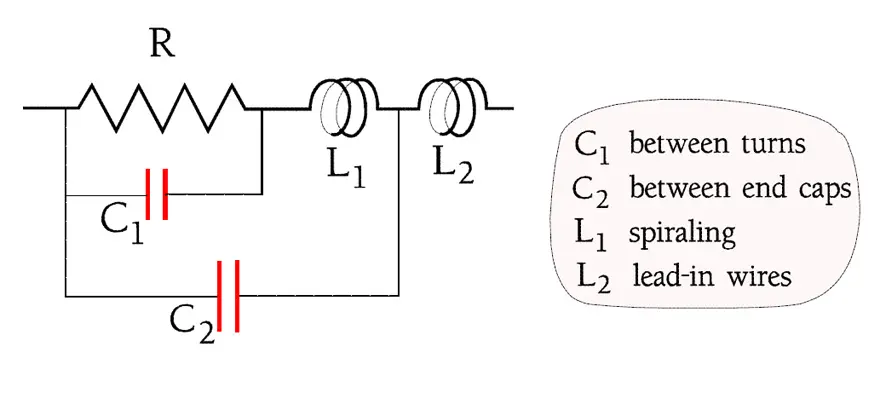

As indicated in the figure a stray capacitance is developed between the turns. Because the turns also constitute a coil the resistor will get a certain inductance. All in all the spiraling produces a frequency dependent impedance where the capacitance is dominating. The conditions are illustrated by the Figure 3.

Film resistors may be approximately classified as follows:

- values < 100Ω are inductive.

- values between 100Ω and 470Ω are practically true resistive.

- values above 470Ω are capacitive.

SMD Chip Resistor Types

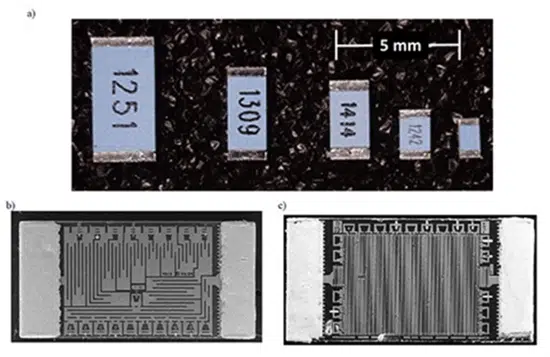

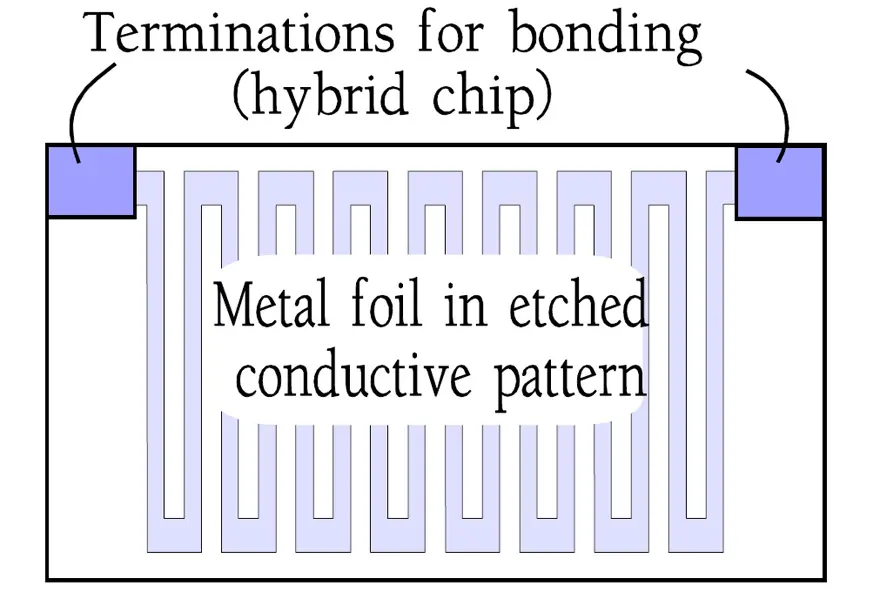

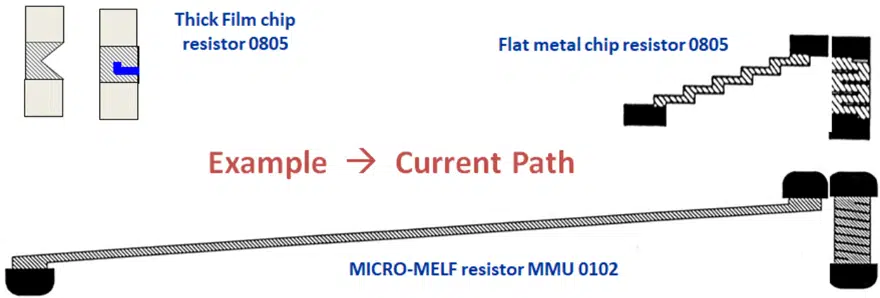

The predominant part of all chips are manufactured with thick film, but thin film chips are becoming more and more common. Also metal foil exists as SMD. The construction is like the one in Figure 4. Certain types have an organic protection in one or two layers on top of the glass passivation.

The substrates are screen printed either with a metal powder paste that is fired to a metal glaze / thick film. Or metal foils are glued on a substrate or metal films are vaporized or ion implanted on it.

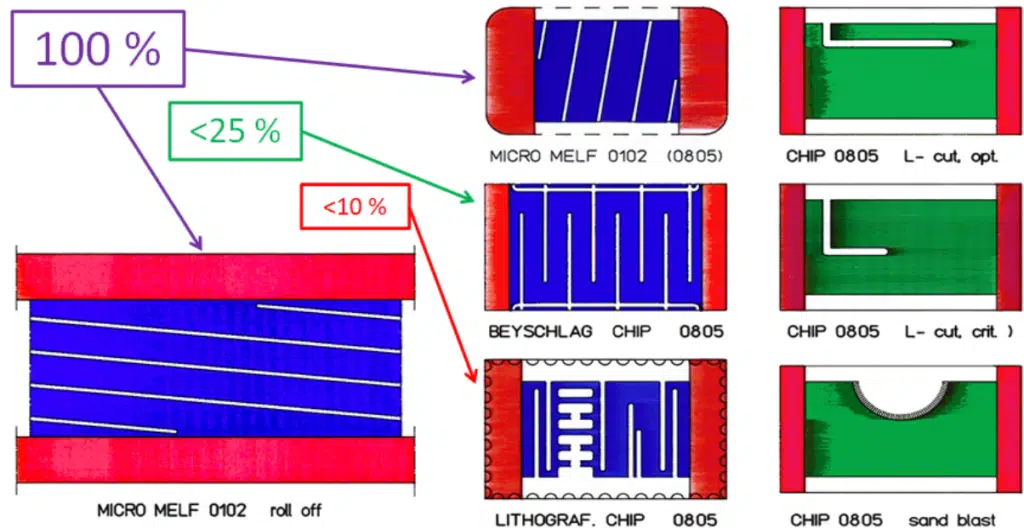

The thick film is laser trimmed to the right resistance value by cutting a track in the long side of the film. Recent manufacturing improvements however begin making this laser trimming unnecessary. This approach without any trimming tracks will increase the pulse load capability by 2 to 3 times. The other films are designed to an inductance-reducing serpentine pattern according to Figure 5. and 6.

The metal foil pattern is etched chemically or patterned by means of an ion beam. The thin metal films are applied through a mask to the desired shape.

Thin Film Chip vs MELF vs Leaded Styles

Construction Overview

| Feature | Thin film chip (SMD) | Metal film MELF | Metal film leaded (axial) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate | Planar alumina chip | Cylindrical alumina body | Cylindrical alumina rod |

| Film | Sputtered metal alloy (Nichrome/TaN) | Sputtered/plated metal film | Sputtered/evaporated metal film |

| Trimming | Laser / photo‑etched pattern | Helical laser spiral or pattern | Helical laser spiral |

| Terminations | Ni barrier + Sn solder terminations | End caps + plating | Axial leads welded to end caps |

| Protection | Epoxy / passivation over film | Lacquer / molding | Lacquer / molding / sometimes hermetic |

Electrical and Application Aspects

- Thin film chips: best for automated assembly, minimal parasitics if layout is short and wide; used where compact precision is needed.

- MELF: cylindrical geometry enables longer current path and higher allowable surface load and pulse capability than equivalent chip sizes.

- Leaded metal film: convenient for through‑hole, elevated mounting, and better creepage in high‑voltage or legacy designs.

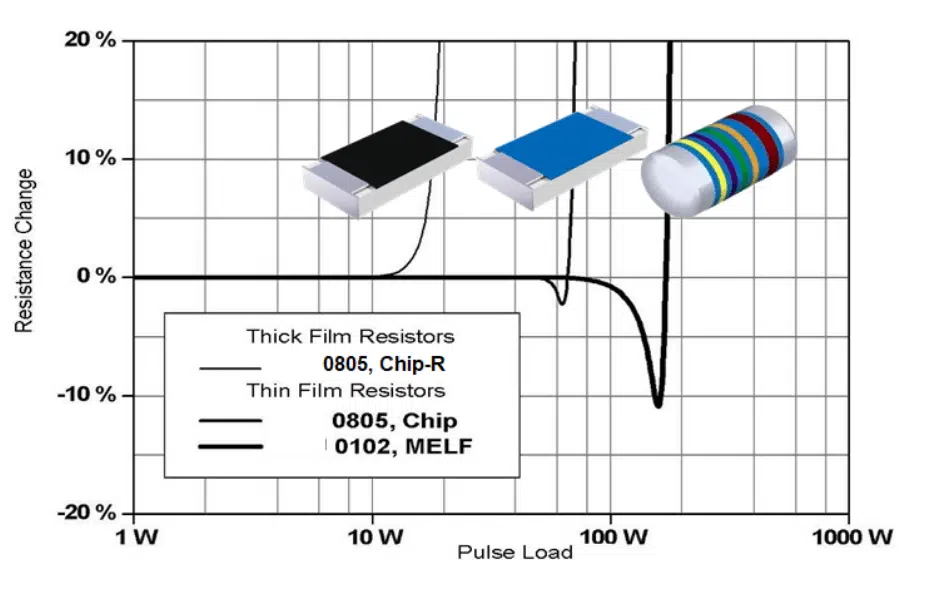

Figures 4.–6. in the source show that for the “0805 equivalent” footprint, the MELF design allows higher surface loading and better pulse endurance than thin or thick film chips.

MELF capacitors that are also available in (micro)-chip case sizes have its advantage with possible path around the whole chip that makes it more efficient compare to Thick/Thin film SMDs. See the current path example on 0805 chip equivalent in Figure 9. below and pulse load capability comparison in Figure 10.:

The differences in effective current length path are also reflected in the possible surface loads [W/mm2]. See the Figure 11. below.

Metal Foil Precision Resistors as a Special Case

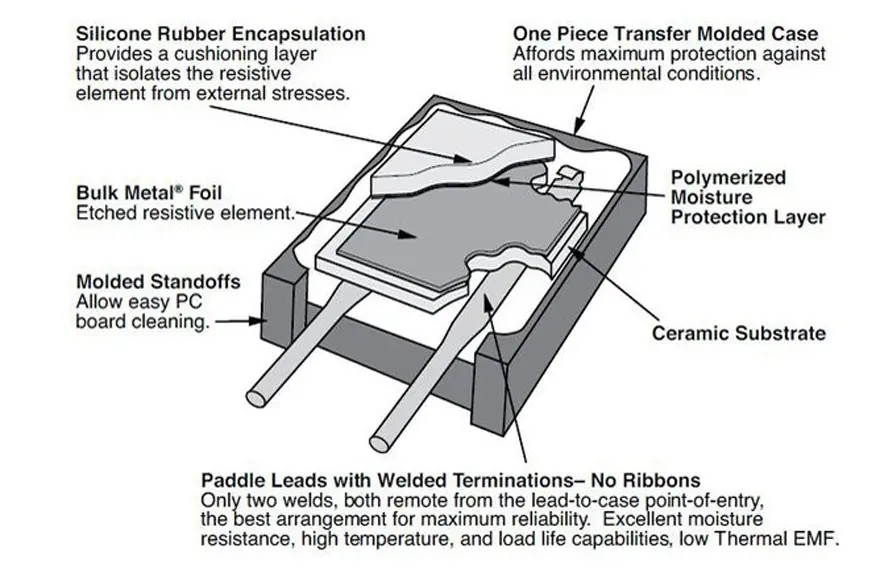

Metal foil resistors use a relatively thick metal foil (≥2.5 µm) bonded to a ceramic substrate; the composite is designed so that thermal expansion of the foil is mechanically constrained by the substrate.

Within the metal film technology there is a particular type of precision resistor made by metal foils, by the inventor, Vishay, called Bulk metal foil. These resistors exist both in axial and radial designs for hole mount, further as SMDs, networks and power styles, finally also in PTC designs.

Figure 12. shows a principle cutaway view of a foil resistor from the manufacturer VPG foil resistors. The etching pattern is not shown.

Key points:

- TCR and stability are improved by matching foil resistivity vs temperature to the stress induced by substrate expansion, yielding very low net TCR and drift.

- The foil is photo‑etched or ion‑etched into serpentine or labyrinth patterns that minimize inductance and allow fine trimming.

- Foil thickness gives excellent pulse handling and eliminates the extreme corrosion sensitivity of ultra‑thin films.

- Maximum resistance value is limited compared with thin film, so foil is typically used at low–medium values where ultra‑precision is demanded.

Failure modes are mainly open contacts or local resistance shifts where weak spots in the foil pattern burn out.

Electrical Characteristics and Performance Ranges

Typical Parameter Ranges

The table below consolidates film‑technology ranges relevant to design.

| Parameter | Thin / metal film | Metal foil | Thick film (for comparison) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical resistance range | 0.2 Ω – 20 MΩ | up to a few hundred kΩ–MΩ (limited) | 1 Ω – 100 MΩ |

| Tolerance | ±0.1% – ±2% | ±0.005% – ±0.1% (vendor‑specific) | ±1% – ±5% |

| TCR | ±5 – ±50 ppm/°C | near zero to ±2–5 ppm/°C (typ.) | ±50 – ±200 ppm/°C |

| Max operating temperature | ≈155 °C | similar or higher (per datasheet) | ≈155 °C |

| Max operating voltage | ≈50 – 500 V (size‑dependent) | similar to film of same size | ≈50 – 200 V |

| Non‑linearity (3rd harmonic) | >110 dB | excellent (very low) | >50 dB |

Thin film resistors can also be configured as linear PTC devices with TCR in the +2000 to +6500 ppm/°C range.

Noise, Voltage Coefficient and Long‑Term Stability

Noise

- Thin/metal film: low excess noise due to homogeneous metallic conduction; TaN films provide particularly low current noise for audio.

- Thick film: granular conduction and laser‑trim micro‑cracks cause significantly higher noise and worse 3rd‑harmonic behavior.

- Metal foil: among the quietest resistor technologies thanks to uniform foil and low trimming damage.

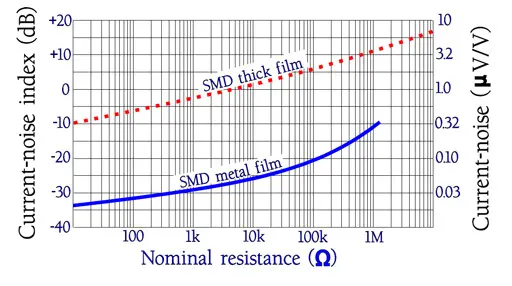

Figure 8. compares current noise vs resistance, clearly favoring thin film over thick film; foil is typically even better.

Voltage Coefficient and Linearity

- Helical metal films are already highly linear; remaining non‑linearity is mainly from voltage coefficient and self‑heating.

- Thick film has noticeable non‑linearity at relatively low resistances due to its complex conduction network.

- Metal foil achieves outstanding voltage coefficient and linearity by design of the foil/substrate system and serpentine pattern.

Long‑Term Stability

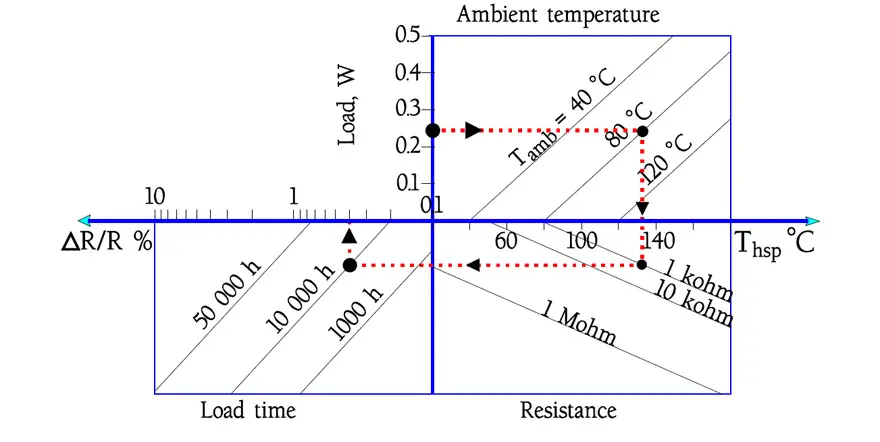

- Stability improves strongly when power and ambient temperature are derated relative to nominal ratings.

- IEC classes allow very tight stability (down to 0.05%) for precision thin film styles rated at lower power and temperature.

- High‑precision parts are aged during manufacture to release early drift before shipment.

Nomographic load charts like Figure 13. relate power, hotspot temperature, ambient and resistance to expected drift; designers should verify that expected drift over life meets budget.

In general, thin film designs are providing better longer term stability, lower noise and robustness against soldering heat as shown in the following Figures 14.:

Thick vs Thin Film Summary Comparison

Thin film chip resistors offer the ability to achieve much better TCR and absolute resistance tolerances because of their material uniformity and consistency as well as their calibration process. The significantly higher element material density, the uniformity, and the improved heat conduction of the thin film element all provide better precision, stability, and lower electrical noise with improved high frequency characteristics.

The strength of thick film resistors is low cost, wider resistance range, and inherent moisture withstanding capability. Pulse handling for thin film is better for longer term pulses, but thick film resistors are better for short pulses of 0.0001 second and shorter.

Temperature, Humidity and Drift Considerations

Temperature Effects

- TCR defines reversible change with temperature; drift adds irreversible change with time and stress.

- Thin film can achieve ±5…±25 ppm/°C, but finest TCR grades often apply over a restricted temperature range.

- Linear PTC thin films use alloys with intentionally high positive TCR for sensing or compensation.

Metal oxide films can be used at much higher hotspot temperatures (up to ≈275 °C in some power types) because the film is already oxidized.

Humidity and Corrosion

- Very thin metal films (≤350 Å) are highly sensitive to moisture‑related electrolytic corrosion, especially CrNi; designers should avoid using the very highest catalogued values in harsh environments.

- Robust encapsulation (multi‑layer lacquer or hermetic sealing) substantially improves humidity performance; multi‑layer lacquers can outperform some molded plastics.

- Tantalum nitride and specially processed Nichrome thin films offer improved moisture resistance.

As a rule of thumb, avoid using values near the maximum available resistance for a given size in high‑reliability thin film designs and verify multiple suppliers’ limits.

Pulse and Overload Capability

Thin film and metal film resistors are sensitive to power pulses because the thin track heats rapidly.

- Conservative guidance: keep repetitive pulse power ≤2× rated power (PR) and avoid exceeding 4× PR even if average power is within limits; single pulses may be higher but must be checked against manufacturer’s pulse curves.

- Very low‑ohmic metal film parts historically used plated alloy layers (1–5 µm) without spiraling, with much better pulse capability but poorer tolerance and TCR; modern sputtered low‑ohm thin film improves precision but sacrifices some pulse strength.

MELF geometries permit longer current paths and higher permissible surface power density than the equivalent chip sizes; comparative curves (Figures 11–12) show MELF outperforming both thin and thick film chips for pulse load on an 0805‑equivalent footprint.

Layout and PCB Design Recommendations

For thin/metal film resistors:

- Maintain at least ≈0.5 mm clearance or insulation to adjacent conductors or metal parts to avoid arcing and local heating.

- For axial parts, consider mounting them slightly above the PCB for better cooling and creepage at higher voltages.

- Minimize loop area and lead length in precision and RF circuits to reduce inductive effects, especially with spiral‑trimmed leaded parts.

- Avoid placing precision resistors in hotspots (near power devices) and in high humidity zones (board edges, vents) unless rated and encapsulated accordingly.

- For high‑precision or high‑voltage networks, use matched resistor networks or arrays on a common substrate for tighter tracking.

When high surge or ESD exposure is expected, verify specific pulse and ESD ratings; close‑tolerance, ultra‑thin films can be more ESD‑sensitive.

Typical Applications for Thin and Metal Film Resistors

- Precision gain and reference chains in instrumentation amplifiers, ADCs, DACs and sensor front‑ends.

- Low‑noise feedback resistors in audio pre‑amps, filters and active crossovers.

- Precision RC networks for time constants and filters in communication and control systems.

- Linearity‑critical circuits (e.g. integrators, precision current sources, VCO control paths).

- High‑stability dividers for voltage references, metering and calibration instruments; foil resistors dominate at the top tier.

- Linear PTC metal film resistors as temperature sensors or compensation elements in analog paths.

Thick film and carbon technologies remain preferable where cost and high‑value range dominate over precision and low noise.

When to Prefer Thin Film over Thick Film

Practical Selection Guide

Use thin/metal film instead of thick film when:

- Tight tolerance and low TCR are required (≤1% and ≤50 ppm/°C, often better).

- Low current noise or very good linearity is essential (audio, precision analog, RF front‑end).

- Long‑term stability and low drift are important (industrial, medical, measurement equipment).

- Voltage coefficient and 3rd‑harmonic distortion must be minimized.

Use thick film instead of thin film when:

- Cost and very wide resistance range (up to 100 MΩ and more in small chips) are primary.

- Short, high‑amplitude pulses (≤100 µs range) dominate and noise/linearity are less critical.

- High‑ohmic, high‑voltage networks with good moisture robustness are needed and precision can be modest.

Key Thin vs Thick Film Chip Characteristics

| Characteristic | Thin film chip | Thick film chip |

|---|---|---|

| Film thickness | ≈0.1 µm | ≈100 µm |

| Process | Sputtering (vacuum deposition) | Screen / stencil printing |

| Tolerance | ±0.1 – ±2% | ±1 – ±5% |

| TCR | ±5 – ±50 ppm/K | ±50 – ±200 ppm/K |

| Resistance range | ≈0.2 Ω – 20 MΩ | ≈1 Ω – 100 MΩ |

| Non‑linearity | >110 dB | >50 dB |

| Noise, stability | Low noise, high stability | Higher noise, lower stability |

Conclusion

Thin film, metal film, and metal foil resistors represent the precision tier of resistor technologies, offering superior performance in tolerance, TCR, noise, and long-term stability compared to thick film alternatives. Metal foil resistors occupy the highest-precision niche with near-zero TCR and exceptional linearity, while standard thin and metal film types serve the broad range of precision analog, measurement, and low-noise applications.

Selection between thin film and thick film hinges on specific circuit requirements: choose thin film when tight tolerance, low noise, excellent stability, and minimal voltage coefficient are critical; select thick film when cost, wide resistance range, and short-pulse capability take priority. MELF geometries offer advantages in pulse handling and surface power density for equivalent footprint sizes.

Proper derating, careful PCB layout, attention to humidity exposure, and awareness of pulse limitations are essential to realizing the full potential of thin and metal film resistors in demanding applications.

FAQ: Thin Film and Metal Film Resistors

Thin film resistors use a homogeneous metallic alloy film (typically Nichrome or TaN) with thickness of approximately 0.1 µm, deposited through sputtering. They offer precision tolerances of ±0.1-±2%, TCR of ±5-±50 ppm/°C, and low noise characteristics. Thick film resistors use screen/stencil printing with film thickness of approximately 100 µm, offering tolerances of ±1-±5%, TCR of ±50-±200 ppm/°C, and are more cost-effective with wider resistance ranges.

Choose thin film resistors when you need tight tolerance (≤1%), low TCR (≤50 ppm/°C), low current noise, excellent linearity, long-term stability, and minimal voltage coefficient. They are ideal for precision analog circuits, audio applications, instrumentation amplifiers, ADC/DAC reference paths, and measurement equipment.

Ultra-Precision Applications

Metal foil resistors occupy the highest-precision niche with near-zero TCR (±2-5 ppm/°C) and exceptional linearity. They are ideal for metrology, reference circuits, voltage references, metering, calibration instruments, and applications requiring tolerances as tight as ±0.005-±0.1%. The foil thickness (≥2.5 µm) provides excellent pulse handling and eliminates corrosion sensitivity.

Construction and Performance Comparison

Thin film chips use planar alumina substrates with laser/photo-etched patterns, offering minimal parasitics for automated assembly. MELF (Metal Electrode Leadless Face) resistors have cylindrical geometry enabling longer current paths, higher surface load capability, and better pulse endurance than equivalent chip sizes. Leaded metal film resistors are convenient for through-hole mounting, elevated positioning, and better creepage in high-voltage applications.

Thin/metal film resistors offer tolerances of ±0.1% to ±2% with TCR of ±5 to ±50 ppm/°C. Metal foil resistors achieve ±0.005% to ±0.1% tolerance with near-zero to ±2-5 ppm/°C TCR. Thick film resistors typically provide ±1% to ±5% tolerance with TCR of ±50 to ±200 ppm/°C.

Moisture and Corrosion Considerations

Very thin metal films (≤350 Å) are highly sensitive to moisture-related electrolytic corrosion, especially CrNi films. Robust encapsulation using multi-layer lacquer or hermetic sealing substantially improves humidity performance. Tantalum nitride and specially processed Nichrome thin films offer improved moisture resistance. Avoid using maximum resistance values in harsh environments for high-reliability designs.

Thin film resistors are sensitive to power pulses due to rapid heating of the thin track. Conservative guidance: keep repetitive pulse power ≤2× rated power and avoid exceeding 4× rated power even if average power is within limits. MELF geometries permit higher permissible surface power density than equivalent chip sizes. Thin film handles longer pulses better, while thick film excels at short pulses (≤0.0001 second).

Design Best Practices

Maintain at least 0.5 mm clearance to adjacent conductors to avoid arcing and local heating. For axial parts, mount slightly above PCB for better cooling and creepage at higher voltages. Minimize loop area and lead length in precision/RF circuits to reduce inductive effects. Avoid placing precision resistors in hotspots (near power devices) or high humidity zones unless properly rated and encapsulated.

Thin/metal film resistors cover 0.2 Ω to 20 MΩ. Metal foil resistors are typically limited to a few hundred kΩ-MΩ due to manufacturing constraints. Thick film resistors offer the widest range at 1 Ω to 100 MΩ or more, making them cost-effective for high-value applications.

TCR and Drift Characteristics

TCR defines reversible change with temperature, while drift adds irreversible change with time and stress. Thin film achieves ±5 to ±25 ppm/°C TCR, with finest grades applying over restricted temperature ranges. Stability improves significantly when power and ambient temperature are derated. High-precision parts are aged during manufacture to release early drift before shipment.

How to Select the Right Film Resistor

- Define Your Circuit Requirements

Identify the key specifications needed for your application: required tolerance (±0.1% for precision, ±5% for general purpose), Temperature Coefficient of Resistance (TCR) limits, operating temperature range, resistance value range, noise requirements, and long-term stability needs. Document voltage coefficient linearity requirements and pulse/ESD exposure levels.

- Evaluate Tolerance and TCR Requirements

For tight tolerance (≤1%) and low TCR (≤50 ppm/°C), select thin film or metal film resistors. For ultra-precision (≤0.1% tolerance, ≤5 ppm/°C TCR), choose metal foil resistors. If tolerance of ±1-5% and TCR of ±50-200 ppm/°C is acceptable, thick film resistors offer cost advantages.

- Assess Noise and Linearity Needs

For low-noise applications (audio, precision analog, RF front-ends), thin film offers homogeneous metallic conduction with low excess noise. Metal foil provides the quietest performance with non-linearity >110 dB. Thick film exhibits higher noise due to granular conduction and is acceptable only when noise is not critical.

- Consider Environmental Factors

For high humidity environments, verify encapsulation quality (multi-layer lacquer or hermetic sealing). Avoid very thin films (≤350 Å) in moisture-prone areas. Tantalum nitride and processed Nichrome offer better moisture resistance. For high-temperature applications (>155°C), consider metal oxide films which can operate up to 275°C.

- Analyze Pulse and Power Requirements

For repetitive pulses, keep pulse power ≤2× rated power for thin film. MELF geometries offer superior pulse handling versus equivalent chip sizes due to longer current paths. For short high-amplitude pulses (≤100 µs), thick film performs better. Verify manufacturer pulse curves for specific conditions.

- Choose the Appropriate Package Style

Select thin film chips (SMD) for automated assembly with compact precision needs. Choose MELF for higher surface load capability and better pulse endurance in equivalent footprints. Use leaded metal film for through-hole mounting, elevated positioning, and better creepage in high-voltage designs.

- Plan PCB Layout for Optimal Performance

Maintain ≥0.5 mm clearance to adjacent conductors. Mount axial parts slightly above PCB for better cooling. Minimize loop area and lead length in precision circuits. Avoid hotspots near power devices and high humidity zones (board edges, vents). Use matched resistor networks on common substrates for high-precision applications.

- Apply Proper Derating Guidelines

Derate power and operating temperature relative to nominal ratings to improve long-term stability. Use nomographic load charts to relate power, hotspot temperature, ambient conditions, and resistance to expected drift. Verify that expected drift over product lifetime meets your stability budget.

- Verify Cost-Performance Tradeoffs

Metal foil resistors provide highest precision but at premium cost and limited resistance range. Standard thin/metal film covers mainstream precision needs at moderate cost. Thick film remains the low-cost workhorse where precision is not critical, offering widest resistance range up to 100 MΩ+.

- Validate Selection with Application Testing

Confirm performance through prototype testing under actual operating conditions. Monitor drift over temperature cycling, verify noise performance in circuit, check pulse response, and validate long-term stability. Compare multiple vendors’ specifications to ensure reliability and availability.