source: EE Times article

LAKE WALES, Fla.—Two wrongs still don’t make a right, but two insulators can make an ultra-high electron density conductor at their interface. According to researchers at the University of Utah and the University of Minnesota, the interface hosts an electron gas that outperforms both graphene and gallium nitride in electron density. Applications range from smaller, cooler running, less power hungry transistors, elimination of “wall warts” (those transformers you plug-in to recharge consumer electronics like laptops) to handheld terahertz modulators.

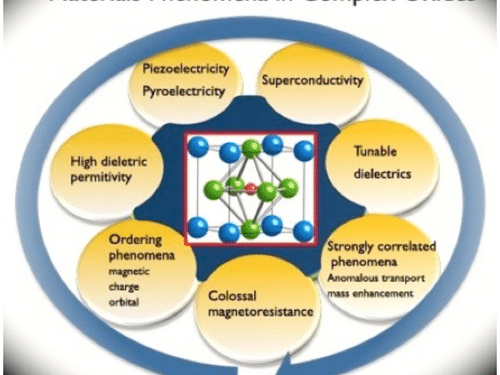

Complex oxides often display impressive multi-functionality, encompassing high temperature superconductivity, colossal magnetoresistance, multiferroicity, and strongly-correlated Mott-Hubbard insulator-type behavior. Moreover, interfaces formed from these materials display interface-stabilized ground states, such as two-dimensional electron gases.

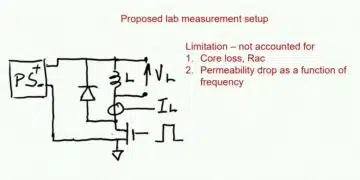

Not just any insulators will do. The complex oxides used by University of Utah professor Berardi Sensale-Rodriguez and University of Minnesota professor Bharat Jalan are neodymium titanate (NdTiO) atop strontium titanate (SrTiO) grown on a commercial LaSr substrate (NTO/STO, see figure). Besides this formulation, which other groups are studying as well, are many other complex oxides being studied that exhibit similar “electron gas” phenomena.

“Complex oxides are actually a subject-of-interest for many groups. For instance, there are very well established groups at the University of California Santa Barbara—where my coauthor University of Minnesota professor Bharat Jalan grew the heterostructure for his PhD, at Cornell, and in Japan, to name a few. However, no other team has shown such a large electron density as what is possible in the samples grown by my coauthor. In this regard, there is an earlier paper published by my colleague [Quasi two-dimensional ultra-high carrier density in a complex oxide broken-gap heterojunction] that discusses the origin of this very high charge density,” Sensate-Rodriguez told EE Times.

When Jalan described the high electron density of his material to Sensate-Rodriguez, he immediately proposed using the technique he was using to evaluate graphene samples—terahertz spectroscopy—to determine its precise electron density, and perhaps uncover the mechanism.

“Based on my previous works in graphene I expected to see a larger conductivity than what is extracted from DC measurements because [terahertz spectroscopy] lets one get closer to the intrinsic properties thus the fundamental limits of the materials,” Sensate-Rodriguez told EE Times. “We were surprised with how large the enhancement we saw was. Specially it bench-marked the conductivity of the two-dimensional electron gas (at the oxide interface) at the same levels of what we typically see in graphene and GaN [gallium nitride]. The interesting thing is that both GaN and these complex oxides benefit from large breakdown fields so are suitable for power electronics.”

They also inferred the mechanism which produced the ultra-high electron density as different from gallium nitride.

“The large conductivity in GaN is a product of a large mobility in the materials, whereas that in NTO/STO is a product of the large electron density together with a not so poor mobility,” Sensate-Rodriguez told EE Times. “These are two fundamentally different approaches that lead to similar results, since the conductivity of a material depends on both the charge density and the mobility of the charges.”

The thing that makes Sensate-Rodriguez and Jalan so optimistic about neodymium titanate atop strontium titanate, is that it is a fresh discovery which has not had be benefit of optimization and yet already preforms as well as gallium nitride or even graphene. Optimization could greatly enhance the new material, perhaps an order of magnitude or more.

“There is still lots of optimization to be done, in particular with respect to the material’s growth. In high quality samples nanoscale and microscale conductivity should approach each other, as what we see in let’s say GaN or graphene,” said Sensate-Rodriguez.

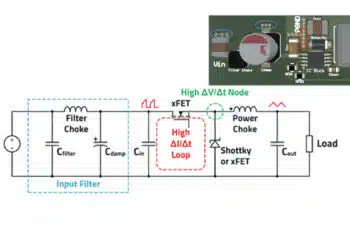

The researchers are also looking beyond the traditional applications of gallium nitride in smaller, less current consuming, cooler running power electronics in electric cars, for instance, and the micro-miniaturization of power supplies (perhaps making them so small that wall-warts can be eliminated by circuitry built into laptops, allowing direct connection to AC). In addition, NTO/STO’s successful modulation in the terahertz regime could also spawn a micro-miniaturization revolution in airport-style scanners, perhaps to handheld size and/or sensitive enough for walk-through versions.

“In terms of applications I see two roads: one in terms of power electronics, and another in terms of terahertz devices, for example, modulators. But the big thing to study now is how to effectively modulate the charge so as to make active devices,” said Sensate-Rodriguez.

Other contributors included University of Utah EE professor Ajay Nahata, graduate students Sara Arezoomandan, Hugo Condori Quispe, Ashish Channa as well as University of Minnesota graduate student Peng Xu. Funding was supplied by the Air Force Young Investigator Research Program at the University of Minnesota, and the National Science Foundation’s Materials Research Science and Engineering Center at the University of Utah.

For all the details read Large nanoscale electronic conductivity in complex oxide heterostructures with ultra high electron density.