This paper supported by prof. Sam Ben Yaakov presentation explores in-depth How transformer works. How MMF (Magnetomotive Force), Flux and Lenz’s Law Control Current Transfer forms the hidden feedback inside transformers. The missing layer: the internal magnetic feedback mechanism that enforces current transfer and keeps transformer flux nearly constant across a wide range of loading conditions.

Key Takeaways

- This paper explores how transformer works by focusing on the hidden feedback mechanism in transformers.

- Transformers function as negative feedback systems influenced by Faraday’s and Lenz’s laws.

- Current transfer occurs without significant changes in flux, as the MMF balance responds to loading conditions.

- The study emphasizes magnetic circuits and the impact of winding configurations on current and flux behavior.

- Key insights include the explanation of why transformers don’t store energy and the importance of phase relationships in AC operation.

Introduction

Transformers are usually introduced as simple voltage-changing devices defined by their turns ratio, yet their internal behavior is far richer than the familiar textbook formulas suggest. The common explanation invokes conservation of energy to move from voltage ratio to current ratio but rarely explains the physical “vehicle” by which currents on one side are linked to currents on the other.

The discussion starts from classical principles—Faraday’s law, Ampère’s law, Lenz’s law and magnetic circuits—and systematically builds a dynamic picture in which the transformer behaves as a tightly closed negative-feedback system. Using that framework, the paper explains why power transfer requires a changing flux, why ideal transformers do not store energy, how magnetizing and load currents interact in phase, and how multi-leg cores can be engineered to route flux and current in non‑obvious ways.

Core concepts of transformer behavior

Voltage ratio and current ratio from Faraday’s law and energy flow

Transformers are governed by the coupled action of Faraday’s law (voltage from changing flux) and Ampère’s law (magnetomotive force from current), with Lenz’s law providing the sign and feedback sense. In integral form, Faraday’s law gives the induced voltage in a winding as

In a conventional two-winding transformer on a high-permeability core, the same core flux links both windings, so the induced primary and secondary voltages are proportional to their respective turns.

For an ideal two-winding transformer sharing the same core magnetic flux ɸ(t), Faraday’s law yields the familiar voltage ratio:

that is valid under sinusoidal steady state and negligible leakage. When the secondary is unloaded, the primary current is limited to the magnetizing current which is largely reactive and approximately 90 degrees lagging the applied voltage in linear cores.

Under steady-state sinusoidal excitation and negligible losses, the instantaneous power balance

leads to the current ratio

These well-known relations are the surface view—the deeper question is how current begins to flow and how flux responds or, surprisingly, does not change under load.

Reluctance and the magnetic circuit viewpoint

Magnetic circuits translate field phenomena into a circuit model. A core segment with length Le, cross-section Ae, and permeability u is characterized by reluctance R with units of H-1.

In this analogy:

- **Flux:** ɸ behaves like current

- **MMF:** F = N . l behaves like voltage

- **Reluctance:** R behaves like resistance.

This mapping enables quantification of magnetization inductance, leakage, and multi-leg core behavior when electrical equivalents alone lack geometric granularity.

In practice, high-permeability transformer cores have low reluctance, resulting in large magnetizing inductance and small magnetizing current for a given applied voltage. This supports the “transformers transfer energy, they do not store it” rule: energy storage per cycle is small compared to the power transferred, unlike in gapped inductors designed for bulk energy storage.

The Transformer as a Negative-Feedback System

Feedback View of MMF and Flux – Faraday’s law, Lenz’s law, and internal negative feedback

The interaction of primary and secondary MMF with core flux can be interpreted directly in control-theoretic terms as a negative-feedback loop. Consider the incremental change when load current on the secondary increases: the new secondary MMF tends to change the core flux, which modifies the induced voltages and hence the currents that feed back to counteract the original disturbance. The “forward path” of this loop is the conversion from MMF to flux through the core reluctance, and the “feedback path” is the conversion from changing flux back to MMF via Faraday’s and Lenz’s laws acting on the coupled windings.

Because the core has high permeability and the windings are tightly coupled, the effective loop gain of this magnetic feedback system is very large. High loop gain drives the closed‑loop error (the change in net flux due to load conditions) toward zero, explaining why the flux waveform is dominated by the applied voltage and only weakly affected by load current. The observable effect of varying load is then not a large change in flux but a proportionate change in primary current, such that the algebraic sum of primary and secondary MMF remains just sufficient to sustain the required flux.

Lenz’s law states that any induced EMF and its resulting current oppose the change in magnetic flux that produced them. In a transformer, this manifests as a back EMF in the primary that opposes the applied voltage and as a secondary current whose MMF opposes the original magnetizing MMF when a load is connected. If the secondary is left open, the induced voltage is present but no load current flows, so the only MMF is from the small magnetizing current required to sustain the core flux.

When a load is connected, the secondary current generates a demagnetizing MMF that initially disturbs the balance between applied voltage and back EMF. To restore the balance, the primary draws additional current from the source so that the net MMF in the core again produces the required flux for the applied voltage waveform.

This automatic adjustment enforces the familiar current ratio , while maintaining nearly constant flux, which is fully consistent with conservation of energy for low-loss operation.

Phase relationships that prevent flux interaction

The core flux ɸ lags the applied voltage V by 90° under sinusoidal steady state (integration phase shift). The load current I2 is (ideally) in phase with the secondary voltage (for a resistive load), hence its MMF aligns with the electrical drive, not ɸ. The Faraday-induced voltage and the load-generated MMF are orthogonal in phase, preventing direct reinforcement: instead, the MMF closes an internal feedback loop that suppresses incremental flux while enabling current transfer.

The demagnetizing MMF associated with load current generates a component of flux that is also in phase with the load current, while the main magnetizing flux is 90 degrees displaced. As a result, the magnetizing and load-related flux components are orthogonal in the phasor sense and can be treated separately when analyzing core utilization and current waveforms. This decomposition clarifies why magnetizing current primarily defines core flux and why load current largely circulates through the copper and source without dramatically altering the core’s flux excursion.

| Quantity | Phase reference (ideal, resistive load) | Relation |

|---|---|---|

| Core flux ɸ | 90° lag vs. input voltage | |

| Secondary voltage V2 | In phase with V1 (scaled by turns) | |

| Load current I2 | In phase with V2 (for R load) | |

| MMF N2 I2 | In phase with V1 | Opposes incremental flux by Lenz’s law |

Why current transfers while flux stays nearly constant

Current transfer proceeds because the MMFs re-balance (via the high loop gain), not because flux rises to carry “more current.” The core acts as the coupling medium setting the boundary condition (for incremental changes), while electrical variables adjust: I2 grows to meet the load, and I1 mirrors I2 by the turns ratio to satisfy power and MMF balance. DC cannot transfer through an ideal transformer since eliminates Faraday voltage and collapses the feedback loop that enables current flow.

| Case | Flux response | Current response | Key reason |

|---|---|---|---|

| AC load connection | Incremental | High loop gain via Faraday + Lenz | |

| DC excitation | No induced voltage | No current transfer to secondary | |

| Strong cancellation | Efficient current transfer | Low reluctance strengthens feedback |

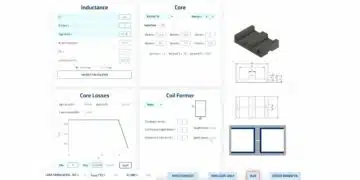

Modified Magnetic Circuit: N²/ℛ as an Effective Inductance

Recasting Winding Effects as Inductances

The standard magnetic circuit model uses dependent sources to represent the coupling between electrical and magnetic domains: MMF sources inject into the magnetic loop, while voltage sources interface core flux back to the electrical terminals. For some analyses it is advantageous to eliminate one set of dependent sources by absorbing their effect into an equivalent inductance.

By combining the relationships and , one finds that a winding on a magnetic branch of reluctance behaves electrically like an inductor with inductance . This matches the classical formula once the expression for reluctance is substituted. In AC analysis, the impedance of this effective inductance is , so large reluctance or low turns produce smaller inductive impedance and higher magnetizing current for a given applied voltage.

Impact on Equivalent Circuit Modeling

Replacing the magnetic branch plus its Faraday interface with an equivalent inductance simplifies circuit simulations and analytical reasoning about how flux chooses its path in a multi‑leg core. When multiple windings share the same core branch, their MMF contributions appear as coupled inductors whose mutual inductance reflects the shared reluctance path. Conversely, when flux can split between core legs with different reluctances or different winding terminations, the effective inductances and load impedances on those branches determine how the total flux divides.

This perspective also emphasizes that any resistance connected to a winding affects not only its electrical loading but also the apparent magnetic impedance of the associated branch. For example, a short-circuited winding on a given core leg presents a very low resistance, which, when transformed via the factor, translates into a large effective admittance in the magnetic domain that strongly influences flux routing through that leg.

| Electrical condition | Equivalent inductance | Magnetic-circuit impedance | Flux steering effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shorted winding (very small R) | Very large | Very large | Flux avoids that leg; shifts to other leg(s) |

| Open winding (very large R) | Very small | Very small | Flux prefers that leg; higher induced voltage |

| Matched resistances (R = R’) | Equal | Equal | Flux splits; voltages share proportionally |

Three-Leg Core as a Case Study in Flux and Current Routing

Structure of the Three-Leg Transformer

Multi-leg cores are common in three-phase transformers, but even in single-phase applications they can be used to implement more complex flux routing behaviors. Consider a three-leg core with a primary winding and an auxiliary winding on the left leg, a “mid-leg” secondary feeding a load, and an additional “switch winding” on the right leg whose termination can be varied from short-circuit to open-circuit through a range of resistive values. All windings are assumed to share the same number of turns for clarity in qualitative analysis.

In such a geometry, the magnetizing flux launched by the primary can choose to return through any combination of the middle and right legs, subject to their reluctances and the effective magnetic impedances imposed by the connected windings and loads. By analyzing this system with the modified magnetic circuit model, the behavior resembles a controllable divider of flux and, by extension, of induced voltages and currents among the secondary windings.

Shorted, Matched and Open “Switch” Conditions

The following table summarizes the qualitative behavior for three key values of the “switch” resistance Rs on the right-leg winding, assuming the mid-leg winding is loaded by a fixed resistor and all relevant turns numbers are equal.

| Switch resistance right leg | Flux in mid leg | Flux in right leg | Mid-leg voltage | Switch-leg voltage | Mid-leg current vs switch current |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very low (≈ short) | High (dominant) | Very small | Near full input | Near zero | Magnitudes nearly equal (same MMF) |

| Mid value (≈ mid-leg load) | Moderate | Moderate | ~½ of input | ~½ of input | Nearly equal currents and MMF |

| Very high (≈ open circuit) | Very small | High (dominant) | Near zero | Near full input | Mid-leg current ~0; switch current finite only if driven elsewhere |

With very small, the shorted winding on the right leg transforms to a large effective magnetic admittance that discourages flux from using that leg as part of its main loop, steering most magnetizing flux through the mid leg instead. This yields substantial voltage on the mid-leg winding and negligible voltage on the shorted switch winding, even though currents in both secondaries can be comparable because their MMF contributions balance along shared parts of the magnetic path.

When is very large (open circuit), the right-leg winding draws negligible current, so its influence on the magnetic circuit is reduced to that of passive turns: most magnetizing flux now prefers the path through the right leg, leaving very little flux and thus negligible induced voltage in the mid-leg winding. At intermediate Rs values comparable to the mid-leg load resistance, the magnetizing flux splits between the mid and right legs, resulting in induced voltages that tend to share the input proportionally.

Interpretation as an Isolated Magnetic “Switch”

From the standpoint of the mid-leg load, the right-leg winding acts like a remote, galvanically isolated “flux switch” that can modulate whether the mid-leg sees significant voltage and current. In the open condition, the mid-leg behaves as if nearly disconnected magnetically, whereas in the shorted condition it captures most of the flux and, with it, most of the available voltage. Although such structures may not be common in standard power transformers, they illustrate how the internal magnetic feedback and flux routing can be exploited for specialized functions such as isolated signalling, fault current redirection, or unconventional gate-drive schemes.

This case study reinforces that current transfer in transformers is not carried by some “flow” of energy within the core but by the enforcement of MMF balance through strong magnetic feedback, which can be intentionally shaped by geometry and winding terminations. Once this viewpoint is adopted, many seemingly paradoxical behaviors—such as high current in a shorted secondary with little net change in flux—become natural consequences of the underlying laws.

Conclusion

Viewing transformers through the combined lenses of magnetic circuits and feedback theory reveals that their “hidden secret” is a powerful internal MMF feedback loop driven by Faraday’s and Lenz’s laws.

The primary voltage dictates the core flux waveform, and the core, in turn, uses induced EMF and MMF balance to force the primary current to track whatever secondary current is required by the external load, keeping flux nearly constant across loading conditions.

This framework clarifies fundamental issues—why energy is not significantly stored in an ideal transformer, why DC cannot be transferred without changing flux, and how phase relationships between voltage, magnetizing current and load current emerge in sinusoidal operation. It also provides practical insight for advanced applications, such as designing multi-leg cores to shape flux paths, interpreting peculiar behaviors in SPICE models, and understanding the limits imposed by leakage, core nonlinearity and finite permeability. For practicing engineers and researchers, embracing this feedback-centric view leads to more intuitive reasoning about transformer behavior and opens the door to novel magnetic architectures that deliberately exploit internal MMF dynamics.

| Design focus | Magnetic-circuit consideration | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Core sizing | Reluctance and flux density limits | Maintain constant flux and avoid saturation |

| Winding placement | Shared vs. separated legs and leakage paths | Control flux steering and coupling |

| Load control | Equivalent inductance via | Predict voltage and current distribution |

FAQ: How Transformers Work

The hidden feedback in a transformer is the internal magnetomotive force (MMF) balance created by Faraday’s and Lenz’s laws, which forces the primary current to adjust so that the core flux remains nearly constant while power is transferred to the load.

Magnetomotive force (MMF) is the product of the number of turns and the current (N × I) and acts as the “magnetic pressure” that drives magnetic flux through the core, analogous to how voltage drives current in an electrical circuit.

When the load current in the secondary changes, the resulting MMF disturbance is counteracted by a change in primary current so that the net MMF and resulting flux match the value required by the applied primary voltage waveform.

Faraday’s law links changing flux to induced voltage in each winding, while Lenz’s law sets the polarity so that induced currents oppose changes in flux, forming a strong negative-feedback loop that stabilizes core flux and enforces the current ratio.

DC does not create a time-varying flux, so Faraday’s law gives zero induced voltage in the secondary and no power transfer can occur in an ideal transformer without changing flux.

A magnetic circuit models the core as a network where flux behaves like current, MMF like voltage, and reluctance like resistance, with reluctance defined as core length divided by permeability times cross-sectional area.

For a winding on a uniform core section, the inductance can be written as L = N² / ℜ, which shows that higher reluctance reduces inductance and increases magnetizing current for a given voltage.

Magnetizing current lags the applied voltage by about 90 degrees because flux is proportional to the integral of voltage, while load current in a resistive secondary is in phase with voltage, making magnetizing and load-related flux components orthogonal in phasor analysis.

In a three-leg core, flux can split between legs according to their reluctances and the effective impedances of the windings, so changing the termination of one leg’s winding can steer flux and redistribute induced voltages between secondary windings.

By varying the resistance or impedance connected to a winding on one leg, a multi-leg core can behave like an isolated magnetic switch that controls whether another winding sees significant flux, voltage and current, which can be exploited in specialized power and signaling applications.