Resistor Network allow a very large miniaturization. This in its turn means short conduction paths and good high resistance over frequency characteristics.

Key Takeaways

- Resistor networks enable miniaturization and improve resistance characteristics over frequency.

- They consist of connected resistor elements in a casing, typically with similar resistance values.

- Different configurations and designs exist, including DIL, SIL, and SMD networks.

- Network characteristics depend on materials, including TCR and absolute tolerance.

- Common failure modes include soldering risks and mechanical weaknesses from thermal and mechanical shocks.

By a network we mean several separate or mutually connected resistor elements collected in a common casing and supplied with terminal leads to each element. Usually the elements have the same resistance value but different values may exist, for example a number of R1 and R2 connected in a ladder pattern that gives a certain voltage division.

In hybrid manufacturing the customer himself applies the resistor elements in a desired casing.

General comments

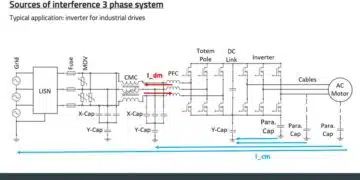

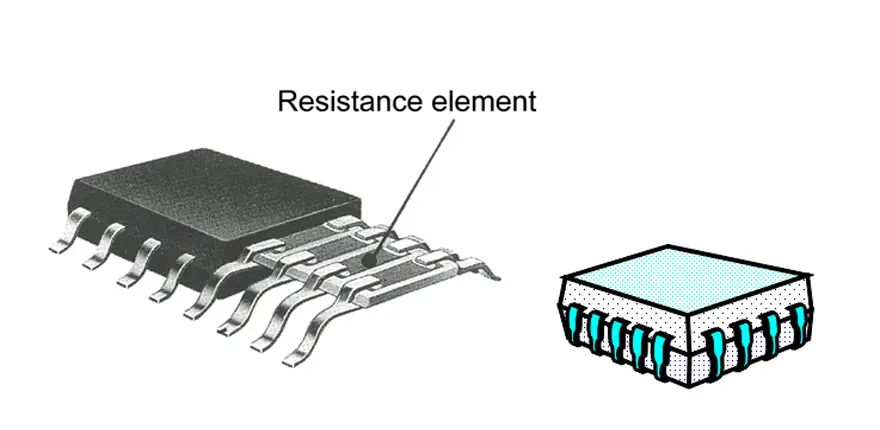

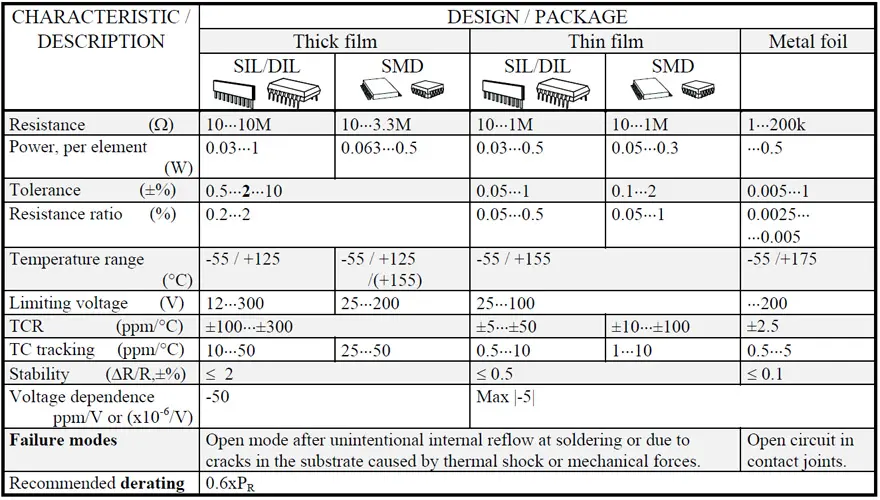

Resistor networks are manufactured both for hole mount and as SMDs. Most parts are manufactured in thick film but thin film as well as metal foil types have a good market.

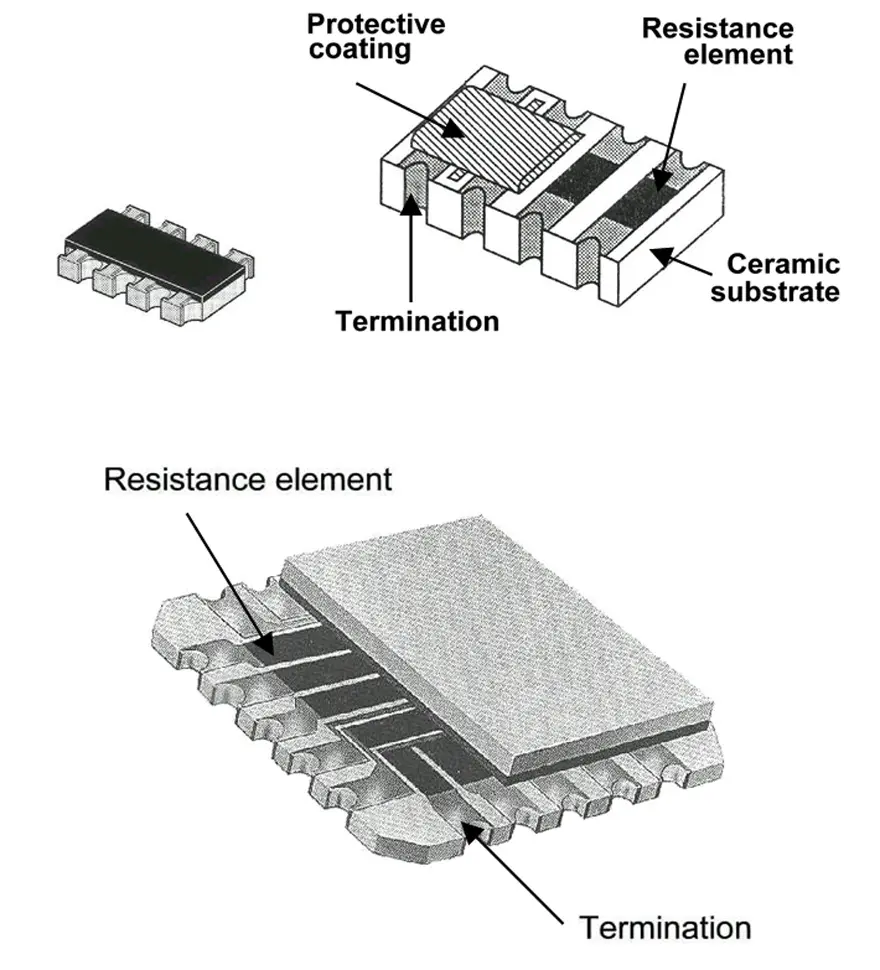

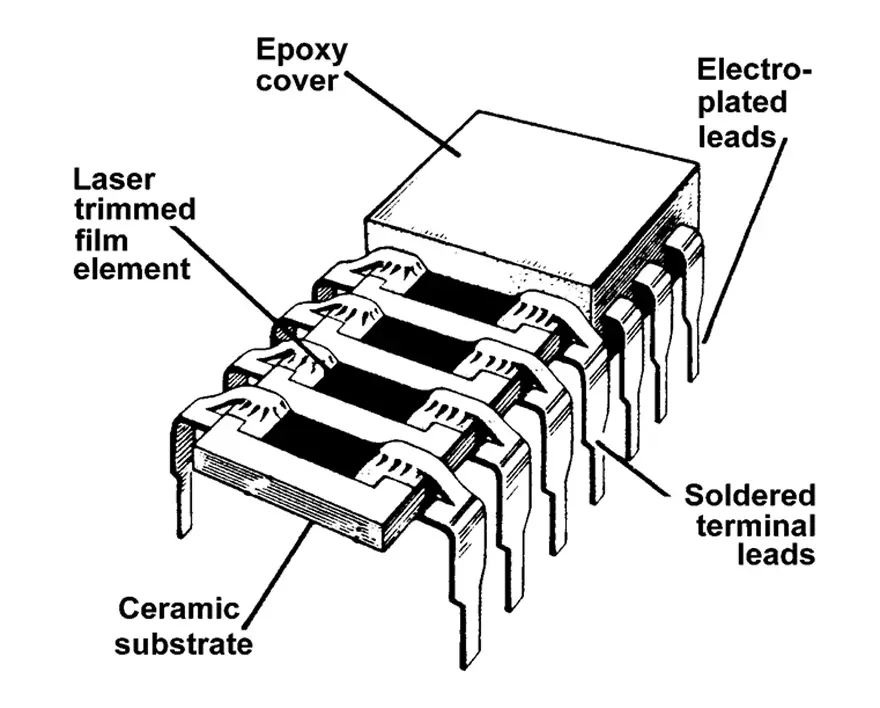

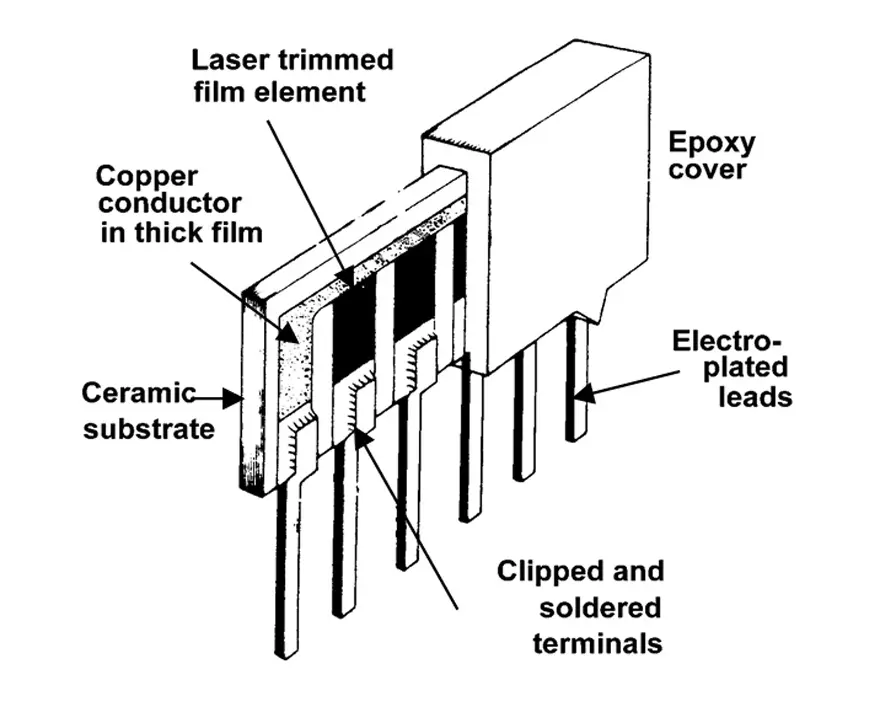

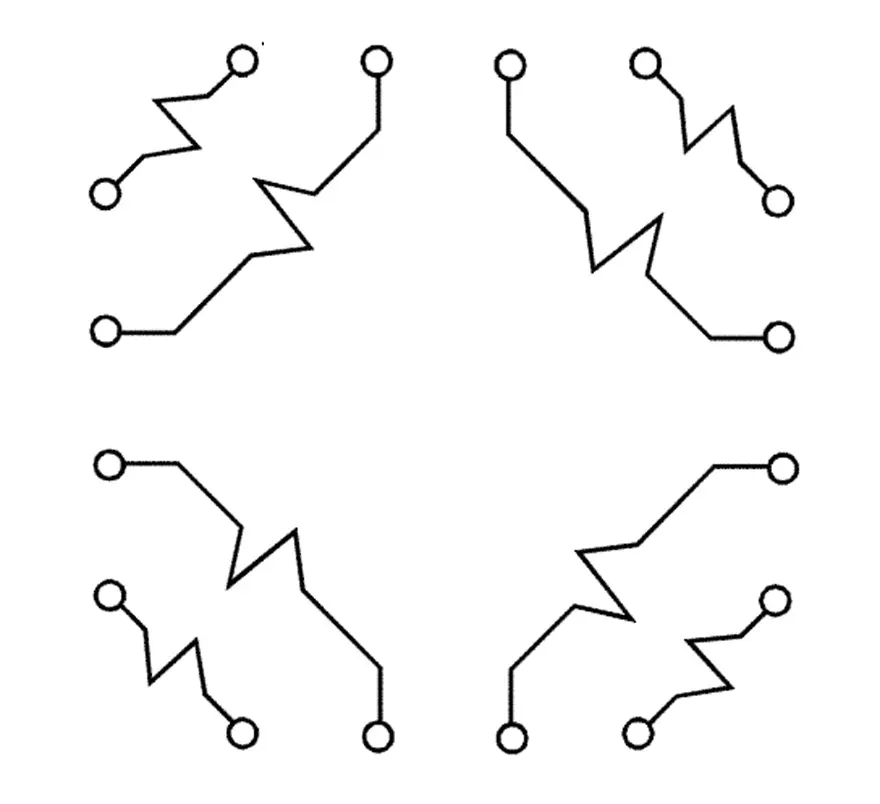

Discrete SM components may be mounted in the network package. But usually the planar substrates are screen printed with a network pattern either with a metal powder paste that is fired to metal glaze/thick film. Or metal foils are glued to the planar substrate or metal films of NiCr or Ta2N are vaporized or ion implanted – sputtered – on the substrates. The thick film is laser trimmed to the desired resistance value by cutting a track in one of the long sides of the film. However, just as with the discrete chips improved manufacturing technology begins making this laser trimming unnecessary. The other films are designed to a serpentine pattern which reduces the inductance of the element. The metal foils get their pattern by a chemical etching process or by means of the cleaner ion beam etching. The thin metal or metal oxide films are applied through a mask to desired shape.

Just as the chips the resistor element films are protected by a glass coat or sometimes a tantalum oxide coating.

Designs

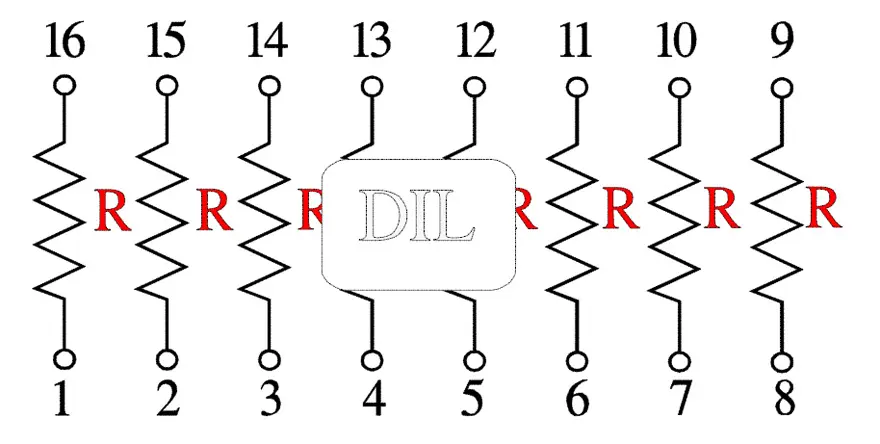

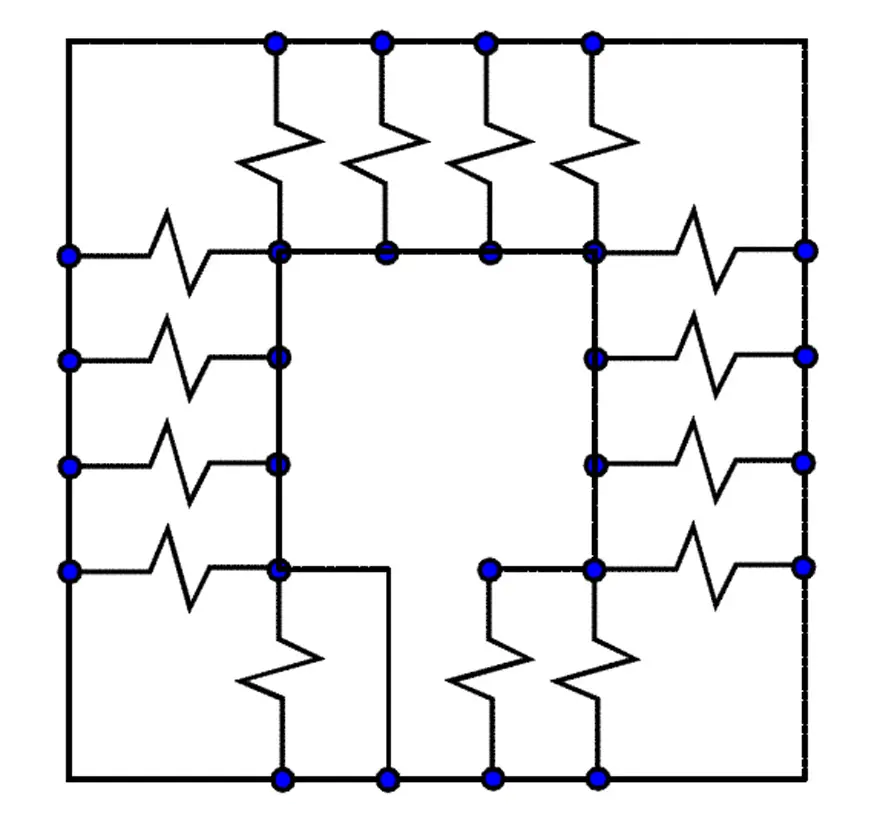

DIL (sometimes DIP) stands for Dual-In-Line respectively Dual-Inline Package (Figure 4.). The number of leads varies; most common are 14, 16 or 18 leads.

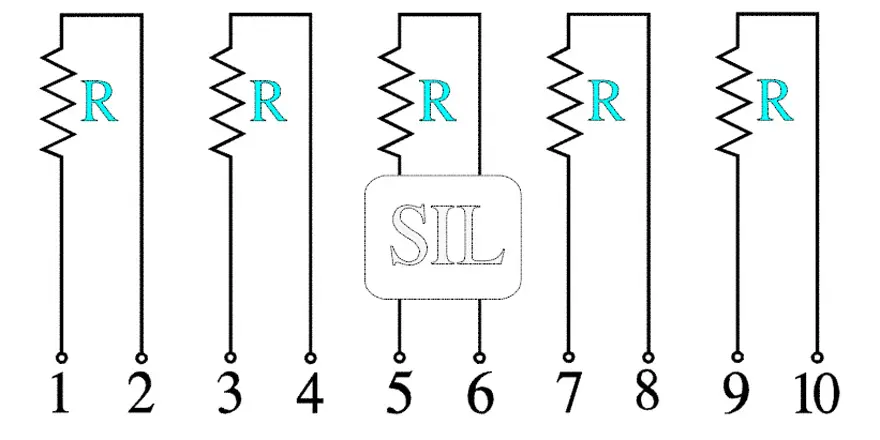

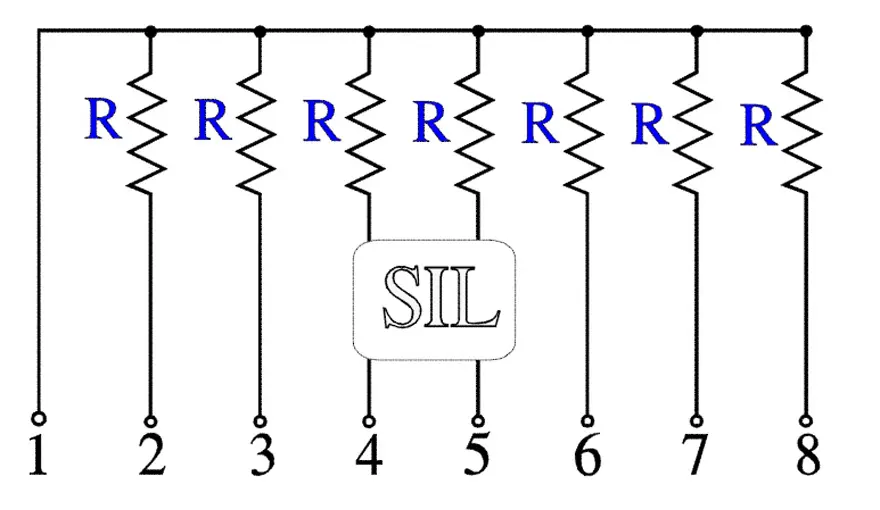

SIL or SIP means Single-In-Line respectively Single-Inline-Package. This network requires less surface but a higher building profile. It exists in the profiles 8 and 5 mm. The latter is most popular. A common number of leads are 4, 6, 8, 10 or 12 (Figure 15.).

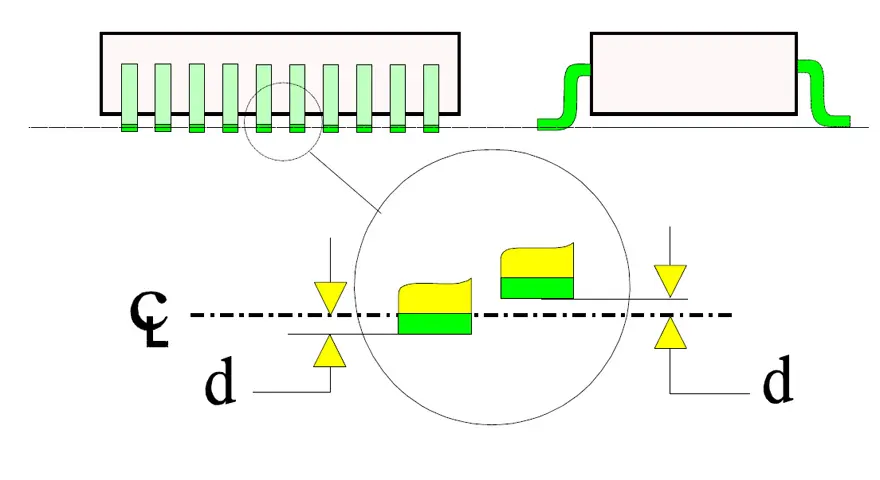

SMD networks exist in many different designs. Some are shown in Figures 8. and 9. . If the application implies considerable temperature changes examples like those in Figure 8. should, due to their lack of flexible leads, be mounted on ceramic substrates.

Of all requirements that have to be specified and checked there is one that is of particular interest: The coplanarity , i.e., the mutual planarity of the leads relatively to a reference plane. If this measure is not met – d in Figure 6. – some leads will be suspended in the air at soldering to the substrate. The measure is exemplified by the gull-wing shape but applies as well to the J hook design.

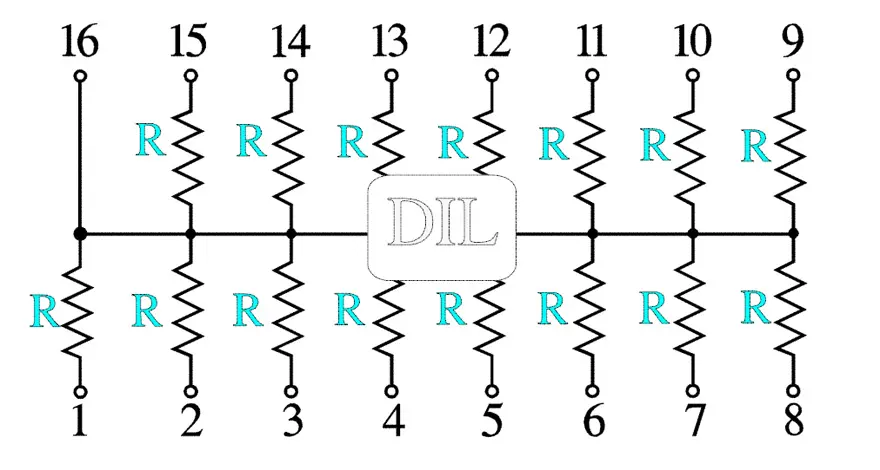

Configurations

The electrical circuit can be arranged in an infinite number of ways. Usually the resistor values are mutually equal. Sometimes they are bussed (common neutral), sometimes they are arranged separately. Figures 7. to 12. show examples of the most common configurations.

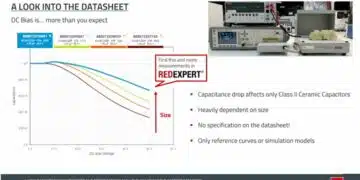

Characteristics

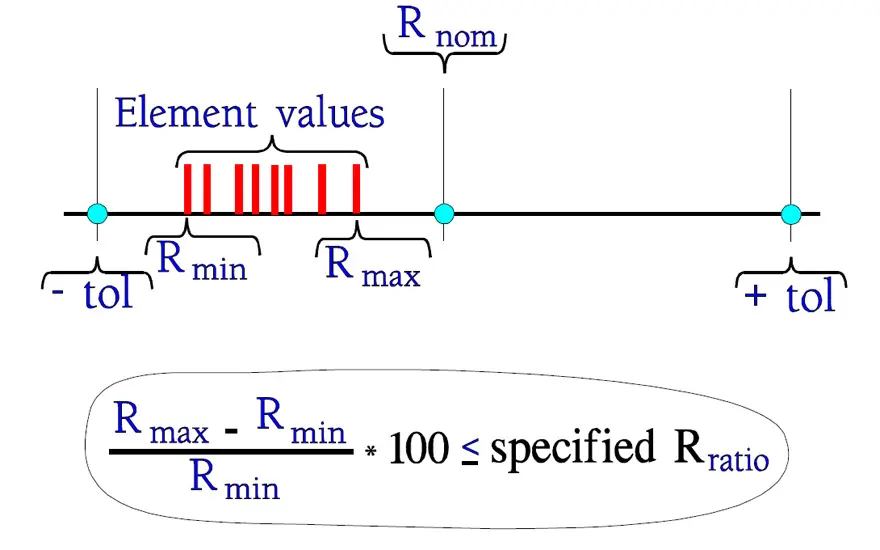

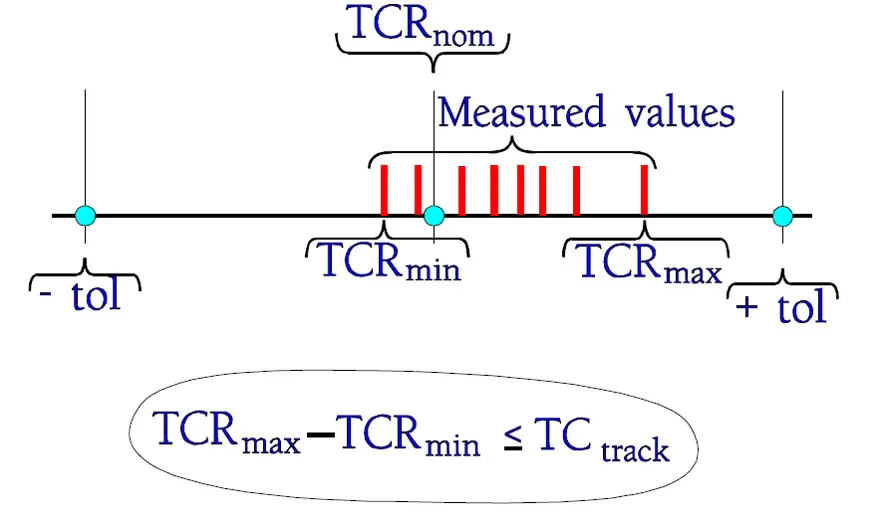

In the first place the characteristics of the networks are determined by the resistor material that rules the TCR and the absolute tolerance. Because the elements included belong to the same manufacturing batch their parameter distribution is much more limited than that of the total production. This enables an additional kind of specification that often is used with precision components: the resistance ratio or relative tolerance and the TCR tracking. The concepts are illustrated in Figures 13. and 14.

In order to understand the resistance ratio concept better we should recollect how the absolute tolerance is constructed. If the actual resistance is called R and the nominal resistance Rnom, the ratio R/Rnom should be within the tolerance limits. With the relative tolerance, however, we mean a comparison of the different element resistances, Rr, with a reference element, Rref, in the network. Rref usually is the first element in the schematic.

The ratio Rr/Rref is called the resistance ratio accuracy, ratio tolerance (or relative tolerance) and is expressed in percent. It is a comparison of magnitude and therefore is given without a sign. If the element values of the network are distributed as in Figure 19. we realize that the largest spread will occur if Rref = Rmin and Rr = Rmax. Thus the resistance ratio accuracy, Rratio, shall fulfill the condition (Rmax – Rmin)/Rmin ≤ Rratio.

The resistance ratios may range over 0.2 to 2 % for the thick film networks and between 0.05 and 1 % for the thin film networks.

In practice the following rule of thumb often applies: TCRtrack ≈ ½ x TCRabs where TCRabs means specified absolute TCR.

TCRtrack for the thick film networks usually lies between 10 and 50 ppm/°C and for the thin film networks between 0.5 and 10 ppm/°C.

Application Examples of Resistor Networks

Resistor networks are most useful where multiple resistors with identical or tightly matched values must be placed close together, with stable ratios and limited PCB space.

1. Digital pull‑up / pull‑down arrays

- Microcontrollers, FPGAs and bus transceivers often require several pull‑up or pull‑down resistors on data, address and control lines.

- Using a SIL or SMD array with common terminal simplifies routing, saves space compared with discrete chips and ensures all lines share similar resistance and TCR, which keeps timing and logic thresholds consistent across bits.

2. Bus termination and line biasing

- Parallel buses (data, address, control) and serial interfaces (for example older LVDS or proprietary links) can use resistor networks for termination and bias networks.

- Bussed networks with a common reference node provide matched impedance and ratio tolerance between lines, improving signal integrity and skew matching while reducing layout length and stub effects thanks to the compact package.

3. DAC and ADC precision networks (R‑2R ladders, dividers)

- Precision R‑2R ladders for DACs and accurate resistor dividers for ADC reference scaling benefit strongly from resistor networks, because ratio accuracy and TCR tracking dominate overall linearity and gain error more than absolute tolerance.

- Thin film or metal foil networks with low ratio tolerance and tight TCR tracking maintain constant ratios over temperature, improving INL/DNL and long‑term stability compared with discrete resistors from different lots.

4. Op‑amp gain‑setting and feedback networks

- In instrumentation amplifiers, sensor interfaces and active filters, resistor ratios in op‑amp feedback paths set gain and filter response.

- Implementing all feedback and input resistors in one network minimizes mismatch and drift between elements, enhancing CMRR, PSRR and gain accuracy, and reducing the impact of temperature gradients across the PCB because all elements share the same substrate and TCR tracking.

5. Voltage dividers and reference distribution

- Multi‑tap voltage dividers (for example generating several bias levels or reference voltages from a single rail) are easily realized with networks that contain multiple equal or ratioed elements.

- Using a single network improves matching between taps, keeps temperature behaviour coherent and reduces error caused by PCB leakage and long traces, since the divider is physically compact with short internal connections.

6. Sensor interfaces and calibration networks

- Bridge sensors, shunts or RTDs often require trimming or calibration resistors to set span, offset or linearization.

- Networks allow manufacturers to integrate fixed and trim elements in one package, sometimes in combination with laser‑trimmed thick film sections, providing stable calibration and reducing the number of discrete parts that could introduce extra tolerances and failure points.

7. Automotive and industrial modules

- Control units in automotive and industrial systems frequently use networks to concentrate pull‑ups, sense dividers and feedback resistors around microcontrollers and drivers, where board space is tight and vibration/thermal cycling are severe.

- Thick film networks in SIL or SMD form reduce solder joints and mechanical stress points compared with many singles, while maintaining sufficient ratio accuracy and TCR tracking for typical system requirements.

8. High‑frequency and mixed‑signal applications

- At higher frequencies, the short internal connections and compact geometry of SMD arrays reduce parasitic inductance and loop areas versus widely spaced discrete resistors.

- When used for terminations, attenuators or bias networks in RF or fast mixed‑signal circuits, suitable network types (often thin film) offer better high‑frequency resistance flatness and channel‑to‑channel tracking, provided layout keeps leads and pads symmetric and minimizes additional stray capacitance.

Failure modes

Soldering risks

Terminations with the usual pitch 0.1″ (2.54 mm) are subjected to a mutual thermal influence at soldering. For SMD networks there will in addition be the closeness to the substrate and the solder pads. Thus, networks run an increased risk of melting internal solder joints. Even if they will solidify after the soldering process there always is a risk of resulting dry joints. Usually this problem is avoided by specifying use of an internal solder with a melting point well above that of the external solder alloy.

Mechanical weaknesses

The ceramic substrates used often are relatively long and thin. Thermal and mechanical shocks as well as vibration may cause cracks in the ceramic under resistor elements and terminations and result in open modes that in the worst case are intermittent and temperature dependent (the nightmare of trouble shooting). Through hole mounted SIL networks run an extra risk of mechanical damage (if somebody, for example, wants to reposition a network that leans after soldering!).

Mechanically exposed designs sometimes are molded in epoxy, foamed plastic or equivalent. Even if the component surfaces are covered with a mould release agent that is intended to prevent the molding compound to get hold of the components due to shape changes during the hardening process it doesn’t solve the problem with, for example, SIL networks. They are very easily exposed to unsymmetrical side forces that may crack the ceramic substrate.

Conclusion

Resistor networks represent a critical advancement in miniaturization technology for electronic circuits, offering significant advantages in terms of space efficiency, performance consistency, and improved high-frequency characteristics. Through their integration of multiple resistor elements within a single package, these components enable designers to achieve compact circuit layouts with shorter conduction paths and enhanced reliability.

The diversity of available designs—from traditional DIL and SIL packages to modern SMD configurations—provides flexibility for various mounting requirements and thermal environments. Whether manufactured using thick film, thin film, or metal foil technologies, resistor networks deliver precise resistance ratios and TCR tracking that exceed what can be achieved with discrete components from the same production batch.

However, successful implementation requires careful consideration of their unique vulnerabilities. Thermal management during soldering, mechanical protection of ceramic substrates, and awareness of coplanarity requirements are essential for long-term reliability. When properly specified and handled, resistor networks offer an optimal balance of performance, miniaturization, and cost-effectiveness for demanding electronic applications

FAQ About Resistor Networks

Resistor networks are integrated components that combine multiple resistor elements within a single package with terminal leads. They are used primarily for miniaturization, offering shorter conduction paths, improved high-frequency resistance characteristics, and enhanced reliability. These components are particularly valuable in applications requiring consistent resistance ratios and TCR tracking across multiple elements.

Resistor networks are available in three main design types: DIL (Dual-In-Line), SIL (Single-In-Line), and SMD (Surface Mount Device) configurations. DIL packages typically have 14, 16, or 18 leads arranged in two parallel rows. SIL networks have leads in a single row and require less surface area but a higher profile. SMD networks come in various designs suitable for surface mounting and are ideal for applications with significant temperature variations when mounted on ceramic substrates.

Resistance ratio accuracy (also called ratio tolerance or relative tolerance) is a comparison of different resistor element resistances within a network relative to a reference element. It is expressed as a percentage and measures the consistency between elements from the same manufacturing batch. This specification is crucial for precision applications because elements within the same network have much more limited parameter distribution than discrete components, typically ranging from 0.2-2% for thick film networks and 0.05-1% for thin film networks.

The two primary failure modes are soldering risks and mechanical weaknesses. Soldering risks arise from mutual thermal influence between closely-spaced terminations, which can melt internal solder joints. Mechanical weaknesses occur because ceramic substrates are often long and thin, making them vulnerable to cracks from thermal shocks, vibration, and mechanical stress. These cracks can result in open circuits that may be intermittent and temperature-dependent.

TCR tracking (Temperature Coefficient of Resistance tracking) measures how closely the temperature coefficients of different resistor elements within a network match each other, while absolute TCR measures the temperature coefficient of individual elements. TCR tracking typically follows the rule of thumb: TCRtrack ≈ ½ x TCRabs. For thick film networks, TCR tracking usually ranges between 10-50 ppm/°C, and for thin film networks between 0.5-10 ppm/°C.

Resistor networks are manufactured using several technologies. Thick film networks use screen-printed metal powder paste that is fired to create metal glaze. Thin film networks use sputtered metal films of NiCr or Ta₂N applied through masks. Metal foil types involve gluing foils to planar substrates or using chemical/ion beam etching. The resistor elements are protected by glass coatings or tantalum oxide, and thick film types are often laser-trimmed to achieve precise resistance values.

How to Select and Implement Resistor Networks

- Determine Your Application Requirements

Identify the specific needs of your circuit including: resistance values needed, tolerance requirements, operating temperature range, frequency characteristics, and available board space. Consider whether you need separate resistors or common terminal (bussed) configurations.

- Choose the Appropriate Package Type

Select between DIL (Dual-In-Line) for through-hole mounting with 14-18 leads, SIL (Single-In-Line) for space-constrained applications with higher profiles, or SMD (Surface Mount Device) for modern surface-mount applications with minimal height requirements. For applications with significant temperature variations, choose SMD networks designed for ceramic substrate mounting.

- Specify the Manufacturing Technology

Choose thick film technology (0.2-2% resistance ratios, 10-50 ppm/°C TCR tracking) for cost-effective general applications, thin film technology (0.05-1% resistance ratios, 0.5-10 ppm/°C TCR tracking) for precision requirements, or metal foil technology for the highest precision and stability requirements.

- Verify Critical Specifications

Check resistance ratio accuracy (relative tolerance between elements), TCR tracking specifications, absolute tolerance of individual elements, coplanarity requirements (especially for SMD types), and voltage/power ratings. Ensure the coplanarity specification meets your assembly requirements to avoid suspended leads during soldering.

- Consider Thermal Management

Verify that internal solder has a melting point well above your assembly process temperature. Plan for adequate thermal dissipation in your PCB layout. Avoid placing networks in areas subject to mechanical stress or vibration. For SMD types, ensure proper pad design and solder volume to minimize thermal stress.

- Implement Mechanical Protection

For hole-mounted SIL networks, provide mechanical support to prevent bending or repositioning after soldering. Consider conformal coating or encapsulation for mechanically exposed designs. Avoid unsymmetrical side forces that could crack ceramic substrates. Design PCB layouts that minimize mechanical stress during thermal cycling.

- Validate Assembly Process

Use appropriate soldering temperatures and profiles. Verify coplanarity after assembly to ensure all leads make proper contact. Inspect for cracks in ceramic substrates, especially after thermal cycling. Test resistance ratios to confirm they meet specifications. Monitor for any temperature-dependent intermittent failures.