This article by Vladimir Azbel, an independent consultant on tantalum capacitors, explains energy transport in tantalum capacitor dielectric that impact its key electrical parameters and features.

Abstract

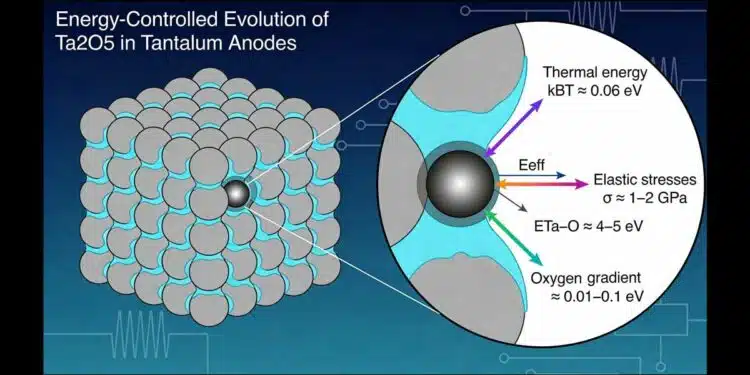

This work demonstrates that changes in capacitance (CAP), leakage current (DCL), and mechanical characteristics (yield strength, Ae) of tantalum anodes in tantalum capacitors after thermal treatment at 450 °C are governed by energy redistribution within the Ta–Ta₂O₅ system rather than by geometrical changes of the oxide layer, which remain invariant under all tested conditions.

Atomic bond energies of Ta–O (≈4–5 eV for amorphous and 7–8 eV for crystalline Ta₂O₅) define the fundamental stability of the dielectric, while thermal energy (kBT ≈ 0.062 eV), internal elastic stresses in the interface zone (≈0.01–0.05 eV per atom), and oxygen chemical potential gradients (≈0.01–0.1 eV) form a narrow energetic corridor enabling reversible structural rearrangements without bond rupture. Mechanical parameters, particularly Ae, are shown to be sensitive indicators of atomic-scale energy redistribution, allowing early diagnostics before electrical failure.

1. Introduction / Motivation

Thermal treatment of tantalum anodes at 450 °C significantly affects CAP and DCL, despite unchanged oxide thickness and anode geometry. This excludes classical explanations based on oxide growth or surface area variation, indicating the presence of an internal controlling parameter related to the energetic state of the Ta–O system.

In amorphous Ta₂O₅, Ta–O bond energies (~4–5 eV) provide sufficient stability to preserve structural integrity during annealing, while crystalline Ta₂O₅, with higher bond energies (~7–8 eV), exhibits increased rigidity and brittleness. At 450 °C, thermal energy (kBT ≈ 0.062 eV), elastic strain energy, and oxygen chemical potential gradients act jointly within a narrow energetic range (~0.02–0.1 eV), enabling oxygen redistribution and local structural relaxation without chemical bond rupture. This energetic framework explains why electrical and mechanical properties evolve while geometric parameters remain unchanged.

2. Interface Zone as an Integral Element of the Tantalum Anode

The metal–oxide interface (IF) zone is an inherent structural element of tantalum anodes formed during powder sintering, electrochemical formation, and subsequent thermal treatments. Rather than being a defect, it represents a natural transition region between metallic tantalum and the amorphous Ta₂O₅ film. /2/

The IF zone is characterized by a non-uniform oxygen distribution, a highly distorted or nanocrystalline structure, and elevated residual mechanical stresses. Maximum oxygen concentration gradients and internal stresses are localized in this region due to differences in molar volume and thermal expansion between the metal and oxide.

Depending on the technological recipe, the interface zone may act either as a mechanical buffer, reducing stress concentration, or as a stress concentrator promoting brittle degradation. Although the interface zone cannot be eliminated, its energetic state can be controlled through the selection of powders, formation parameters, and annealing conditions. This energetic state ultimately governs the dielectric response and long-term stability of the anode.

3. Bond Energy as “Atomic Glue.”

The electrical and mechanical properties of the dielectric share a common origin in the energy of atomic Ta–O bonds. Bond energy determines the resistance of the structure to both bond rupture and collective deformation.

In amorphous Ta₂O₅, Ta–O bond energies of approximately 4–5 eV provide sufficient flexibility for local atomic rearrangements and stress relaxation without loss of film continuity. In contrast, crystalline Ta₂O₅ exhibits higher bond energies (7–8 eV), corresponding to denser atomic packing and increased rigidity, but reduced ability to accommodate stress, leading to brittle fracture. Thus, amorphous and crystalline Ta₂O₅ differ not only structurally but also in their fundamental energetic stiffness.

4. Interpretation of Bond Energy through Macroscopic Mechanical Parameters

In this work, the term equivalent strength level is used as a qualitative indicator of correlated trends between atomic-scale bond stability and macroscopic mechanical response, rather than as a result of direct mathematical conversion between energy and stress units. These characteristics represent two manifestations of the same resistance to loss of structural integrity.

4.1. Qualitative–Correlative Relationship

Atomic Ta–O bond energies (eV) and macroscopic mechanical parameters such as hardness and yield strength (kg/mm² or GPa) differ in physical nature but describe the same fundamental property: structural stability under external and internal perturbations. An increase in bond energy corresponds to increased resistance to collective deformation, whereas a reduction in effective bond energy facilitates local rearrangements and stress relaxation. The correlation between these parameters reflects the inevitable manifestation of atomic-scale changes in macroscopic behavior.

4.2. Comparative Analysis of Ta₂O₅ States

For practical engineering assessment, mechanical parameters serve as a macroscopic echo of atomic-scale physics. Table 1 summarizes characteristic values for amorphous and crystalline Ta₂O₅.

Table 1 — Comparison of atomic and mechanical characteristics of Ta₂O₅

| Oxide state | Ta–O bond energy (eV) | Equivalent strength level (kg/mm²) * | Typical microhardness (HV) |

| Amorphous Ta₂O₅ | 4–5 | 1000–1200 | 700–900 |

| Crystalline Ta₂O₅ | 7–8 | 1700–1900 | 1300–1500 |

Peak mechanical resistance is typically localized within the nanocrystalline interface zone, making it a critical region for the distribution of internal stresses.

4.3. Practical Implications for Reliability Control

Amorphous Ta₂O₅ can accommodate internal stresses through atomic-scale rearrangements without loss of continuity, whereas crystalline Ta₂O₅ is prone to brittle failure once critical stresses are reached, often accompanied by a sharp increase in DCL. From an engineering perspective, the yield strength Ae provides a sensitive and accessible indicator of effective bond stability. A collapse of Ae signals the onset of structural degradation even before catastrophic electrical failure becomes evident.

5. Energetic Factors Governing Annealing at 450 °C

5.1. Ta–O Bond Energy as the Upper Energetic Limit

In amorphous Ta₂O₅, Ta–O bond energies (~4–5 eV) define the fundamental stability of the dielectric and correspond to the energy required for bond rupture. Thermal energy, elastic stresses, and oxygen chemical gradients at 450 °C remain far below this level, ensuring that annealing does not destroy the oxide chemically but induces reversible or quasi-reversible structural rearrangements.

5.2. Thermal Energy at 450 °C

At 450 °C (723 K), atomic thermal energy kBT is approximately 0.06–0.07 eV. Although insufficient for bond rupture, it activates oxygen diffusion, elastic stress relaxation, and local coordination rearrangements, providing the energetic background for annealing-induced evolution.

5.3. Internal Stresses in the Interface Zone

Internal elastic stresses of approximately 1–2 GPa in the interface zone correspond to atomic-scale energies of ~0.02–0.05 eV. These stresses are determined by technological parameters such as powder morphology, sintering conditions, formation voltage, and annealing atmosphere. While they do not rupture Ta–O bonds, they modify the local energetic landscape, influencing diffusion barriers, coordination stability, and relaxation pathways. From an engineering standpoint, internal stresses represent a controllable energetic parameter linking process conditions to material behavior.

5.4. Oxygen Concentration Gradients

Chemical potential gradients of oxygen between the amorphous film, interface zone, and tantalum matrix contribute energies on the order of ~0.01–0.1 eV. Acting jointly with thermal and elastic energies, they govern oxygen migration and defect redistribution.

5.5. Energetic “Corridor” of Processes at 450 °C

All processes responsible for changes in CAP, DCL, and mechanical properties occur within an energy range of ~0.02–0.1 eV per atom, which is two orders of magnitude below the energy required to rupture the Ta–O bond. Consequently, annealing at 450 °C preserves anode geometry and oxide thickness, produces evolutionary rather than abrupt electrical changes, and causes mechanical parameters to respond earlier than electrical ones. The system state remains strongly dependent on annealing atmosphere and technological history, which determine oxygen balance and residual stresses.

Table 2 — Characteristic energy scales in the Ta–Ta₂O₅ system at 450 °C

| Factor | Characteristic energy |

| Ta–O bond rupture | 4–5 eV |

| Thermal energy (kBT) | 0.06–0.07 eV |

| Elastic strain energy | 0.02–0.05 eV |

| Oxygen chemical potential gradient | ~0.01–0.1 eV |

These contributions collectively define an energetic corridor enabling controlled structural rearrangement without catastrophic degradation.

5.6 Engineering Energetic Stability Criterion

The operational stability of the Ta–Ta₂O₅ sandwich structure can be expressed in an engineering form by comparing the total effective local energy acting on the metal–oxide interface with the characteristic Ta–O bond stability threshold.

The effective local energy is defined as:

Eeff=kBT+Eσ+EμO+Eripple

where kBT is the thermal energy, Eσ is the elastic strain energy in the interface and neck regions, EμO represents the contribution from oxygen chemical potential gradients, and Eripple accounts for additional energy input due to ripple current during operation.

Structural stability of the anode sandwich is maintained as long as the following condition is satisfied:

Eeff ≪ETa-O

where ETa–O is the characteristic Ta–O bond dissociation energy.

Under annealing at 450 °C and under nominal operating ripple current conditions, the effective local energy is estimated to be in the range of approximately 0.06–0.10 eV, whereas the Ta–O bond energy is on the order of 4–5 eV for amorphous Ta₂O₅. The ratio Eeff/ETa-O

therefore, remains below ~0.03, explaining why the observed structural evolution proceeds via diffusion–relaxation mechanisms rather than by chemical bond rupture or catastrophic dielectric failure.

6. Engineering Interpretation of CAP / DCL / Ae

CAP reflects changes in dielectric polarizability, DCL indicates defect and vacancy density, while Ae responds first to degradation of the interface zone. Joint analysis enables early assessment of the anode’s energetic state well before failure.

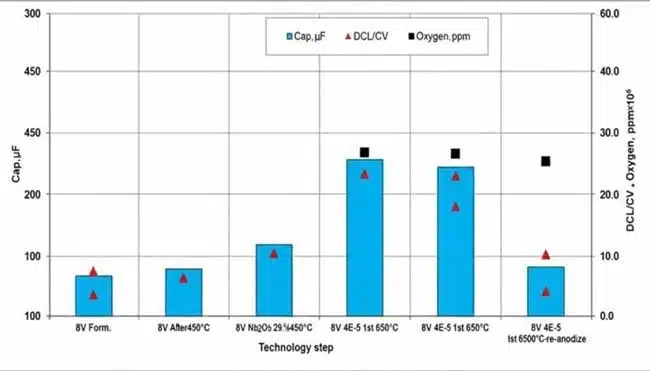

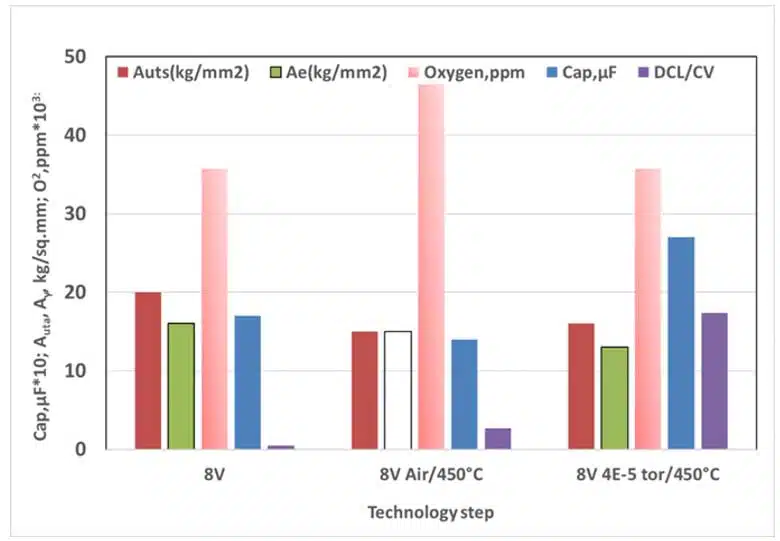

Representative experimental data illustrating the coupled evolution of electrical, chemical, and mechanical parameters under different annealing atmospheres are shown in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2.

7. Practical Conclusions for the Engineer

Changes in CAP and DCL are governed by the energetic state of the amorphous oxide and interface rather than geometry. Monitoring Ae relative to a qualified benchmark anode provides a sensitive criterion: a reduction exceeding ~15 % after 450 °C annealing indicates critical degradation of bond stability.

8. Influence of Ripple Current on the Stability of the Anode “Sandwich” Structure

During the operation of a tantalum capacitor, the alternating component of the load current (ripple current) is the primary electrical factor that directly stresses the metallic phase of the anode. Unlike the forming current, which is mainly consumed by electrochemical growth of the dielectric film, ripple current flows through the porous metallic framework and concentrates in narrow interparticle constrictions (“necks”), thereby defining the local energy balance of the Ta–Ta₂O₅ system.

8.1 Physical Mechanism of Ripple Current Impact

Due to the porous geometry of the anode, the current density distribution is inherently non-uniform. When an AC flows, the dominant energy dissipation occurs in metallic necks with minimal effective cross-section Sneck. In these regions, the following processes are activated:

- local Joule heating, described by Pripple =Iripple² · ESR;

- cyclic thermomechanical stresses caused by periodic temperature variations at the ripple frequency;

- enhanced oxygen diffusion within the metal–oxide interface, leading to gradual oxide growth at the expense of the metallic cross-section of the neck.

Thus, ripple current acts not as a formation mechanism but as a driver of slow geometrical and defect-related evolution of the anode “sandwich”.

8.2 Quantitative Estimate of the Ripple Current Energy Contribution

For typical operating conditions of a MnO₂-based tantalum capacitor, the following parameters may be assumed:

- Iripple= 50–150 mA (RMS);

- ESR = 0.3–1 Ω;

- effective local thermal resistance of a neck region Rθ,neck ≈ 30–80 K/W.

The corresponding dissipated power is:

Pripple ≈ (0.05–0.15) ² · (0.3–1) ≈ 1–20 mW.

The resulting local temperature rise in the neck region is:

ΔTneck ≈ Pripple · Rθ,neck ≈ 3–20 K.

The energy equivalent of this temperature increase is:

ΔEripple ≈ kB*ΔTneck ≈ 0.003–0.017 eV.

8.3 Comparison with Oxide Film Degradation Energetics

For the Ta–Ta₂O₅ interface, the characteristic energy levels are:

- thermal energy at 125 °C: kBT≈ 0.034 eV;

- elastic strain energy in the neck region: Eσ ≈ 0.02–0.05 eV;

- Ta–O bond dissociation energy: Ebond ≈ 4–5 eV.

Including the ripple current contribution, the total local energy level in the neck region is:

Etotal ≈ 0.06–0.10 eV.

This value remains an order of magnitude lower than the bond dissociation energy and well below the effective energy level activated during the high-temperature anode test at 450 °C, where:

kBT450≈0.062eV, E450eff≈ 0.1-0.15eV

8.4 Nature of Degradation under Ripple Current

When ripple current remains within nominal limits, degradation of the anode “sandwich” follows a slow diffusion–relaxation mechanism and manifests as:

- gradual oxide thickening in neck regions;

- reduction of the effective metallic cross-section Sneck;

- smooth logarithmic increase of ESR and DF over time.

The absence of an abrupt increase in the local energy budget explains why parameter drift remains progressive and does not lead to catastrophic structural collapse under normal operating conditions.

Takeaway — Engineering Implications of Ripple Current Loading

Ripple current is the dominant operational factor governing the local energy state of metallic necks and, consequently, the stability of the metal–oxide anode sandwich. Quantitative analysis shows that, at nominal ripple current levels, its energetic contribution to oxide film degradation (≈0.003–0.02 eV) is substantially lower than both the Ta–O bond energy and the energy threshold verified by the 450 °C anode test. This confirms the validity of the high-temperature test as an upper energetic benchmark for long-term anode stability.

9. Predicting Operational Stability via Accelerated Thermal Testing (450°C)

The transition from a static anode model to an analysis of its performance under dynamic loads (Ripple Current) requires an understanding of how the technological formation recipe determines the “energetic buffer” of the system.

9.1. Temperature-Time Equivalence

To justify the reliability of the anode, a calculation based on the Arrhenius law was performed (using an activation energy Ea = 1.2eV). It has been established that a short-term exposure to 450°C for 15 minutes induces structural changes—specifically neck degeneration and interface zone growth—equivalent to long-term operation:

Equivalence: 15 min at 450°C ≈, 2000 hours (service life) at a temperature of ~220°C (effective local neck temperature).

Given that real-world Life Tests are typically conducted at 85–150°C, stability at 450°C ensures a massive safety margin that covers all operational risks.

9.2. Impact of Formation Recipe on Neck Defectivity and Volume

Neck defectivity is a direct result of the technological recipe selected by the developer. The formation process exerts a decisive influence on the structure through the mechanism of stress generation:

Compressive Stresses: The growth of the oxide film (with a Pilling-Bedworth ratio of ≈ 2.5) generates significant compressive stresses on the surface of the metallic neck.

Affected Zone (Degradation Volume): The magnitude of these stresses determines the volume of the neck metal subjected to deformation. Under “harsh” formation regimes, compressive stresses penetrate the entire depth of the neck, transforming it from a ductile microcrystalline conductor into a high-defect zone with a critically reduced metallic cross-section S neck.

Internal Friction: An increase in defect density within the neck volume sharply increases internal friction. Consequently, the energy from the ripple current is dissipated by these defects, causing localized heating directly within the “sandwich” of the interface.

9.3. Ripple Current Contribution (Irms = 0.1A) to Film Degradation

When a ripple current passes through the porous structure, the generated heat is distributed unevenly.

Localized Pressure: In a degenerated neck with high internal friction, a current of 0.1A creates an additional energetic contribution (~0.01 eV).

Total Energy Balance: At 125°C, the sum of thermal energy, residual stresses, and current contribution is approximately 0.06–0.1 eV. While this is an order of magnitude lower than the Ta–O bond rupture energy (4–5 eV), it is sufficient to accelerate oxygen diffusion if the neck is “locked” and cannot effectively dissipate heat.

9.4. The Deceptive Role of Post-Anneal Formation: DCL vs. Ae

In industrial practice, thermal treatment at 450 °C is typically followed by a second formation (re-formation) step. This procedure is intended to “heal” the dielectric film by compensating oxygen vacancies and sealing micro-defects generated during high-temperature exposure. Traditionally, the recovery of a low direct current leakage (DCL) after this step is used as the primary acceptance criterion for tantalum anodes.

However, the proposed energetic model and experimental observations demonstrate that DCL recovery is a deceptive indicator of long-term operational stability, as it does not reflect the underlying mechanical and structural integrity of the Ta–Ta₂O₅ “sandwich.”

1. Electrical Healing vs. Structural Health

While the second formation effectively restores the electrical continuity of the Ta₂O₅ dielectric—manifested by reduced DCL—it does not relieve the accumulated compressive stresses nor reduce the defect density within the metallic neck regions. On the contrary, additional electrochemical oxide growth during re-formation may further increase mechanical loading on an already weakened or partially degenerated neck volume.

Thus, electrical “healing” does not imply restoration of the original mechanical or energetic state of the anode skeleton.

2. The Illusion of Acceptance

An anode may exhibit nominal electrical parameters (CAP, DCL, DF) immediately after the second formation and therefore formally pass incoming inspection. However, if the internal “sandwich” structure has been compromised—i.e., if the energy stored in elastic stresses and interfacial defects has approached the Ta–O bond stability threshold—such an anode is predestined to fail during the Life Test (120 000 min).

Under these conditions, ripple current acts as the final energetic trigger. Localized Joule heating in the stressed neck regions leads to temperature excursions that the mechanically weakened structure can no longer dissipate, despite the presence of an electrically “healthy” oxide film.

3. Ae as the Ultimate Arbiter of Structural Integrity

Unlike DCL, the yield stress parameter (Ae) is fundamentally insensitive to the cosmetic electrical healing effect of the second formation. Ae directly reflects the mechanical state of the metallic skeleton and the metal–oxide interface zone.

- If Ae remains stable after annealing at 450 °C (15 min):

The volume of the neck affected by internal stresses remains limited. The metallic core is preserved, ensuring an effective thermal conduction path to the case surface (Scase). Such an anode is structurally robust and capable of sustaining long-term ripple current loading. - If a collapse of Ae is observed:

The second formation merely masks a terminally degraded structure. Extensive degeneration of the neck volume converts the anode into a thermal trap, where even modest ripple current cannot be dissipated. This inevitably results in catastrophic failure during operational life testing.

Takeaway — Redefining Quality Control Criteria

Reliance on DCL restoration after the second formation as an acceptance criterion is insufficient and potentially hazardous. It allows anodes with masked structural damage to pass quality control.

Only the preservation of the mechanical parameter Ae guarantees that the Ta–Ta₂O₅ sandwich has retained its structural and energetic integrity. Mechanical stability, as quantified by Ae, is the only reliable predictor of electrochemical longevity and the true engineering gate for the 120 000-minute Life Test.

10. Conclusion

The energetics of Ta–O atomic bonds provide the unifying framework linking the mechanical and electrical behavior of tantalum anodes. The metal–oxide interface is a controllable energetic object, and mechanical parameters offer an effective tool for early reliability diagnostics.

Appendix A. Methods / Energetic Assessment

Energetic Contributions in the Ta–Ta₂O₅ System

To quantify the processes governing structural evolution during annealing at 450 °C, the principal energetic contributions in the Ta–Ta₂O₅ system were evaluated on an order-of-magnitude basis.

- Ta–O bond energy

The Ta–O bond energy was estimated using the standard enthalpy of formation of tantalum pentoxide (ΔH°f ≈ –2047 kJ/mol). Assuming approximately five Ta–O bonds per Ta₂O₅ formula unit, the average bond energy is ~409 kJ/mol, corresponding to ~4.2 eV per bond for amorphous Ta₂O₅. Crystalline Ta₂O₅, characterized by higher coordination and structural ordering, exhibits higher effective bond energies in the range of 7–8 eV, as reported in the literature. - Thermal energy

The atomic thermal energy at the annealing temperature (T = 723 K) was estimated as

Eth=kBT≈0.062 eV.

This value is two orders of magnitude lower than the Ta–O bond energy and is therefore insufficient for bond rupture, but sufficient to activate local atomic rearrangements, diffusion processes, and stress relaxation.

- Elastic strain energy

For local elastic stresses of σ ≈ 1–2 GPa in the metal–oxide interface zone and a Young’s modulus of Ta₂O₅ of E ≈ 140 GPa, the corresponding atomic-scale elastic energy contribution was estimated using standard elastic energy density relations. The resulting energy per atom lies in the range of approximately 0.01–0.05 eV, consistent with values reported for stressed oxide interfaces. - Oxygen chemical potential gradients

Gradients in the chemical potential of oxygen between the amorphous Ta₂O₅ film, the interface zone, and the tantalum matrix provide an additional energetic contribution. Based on diffusion and defect thermodynamics data, this contribution is estimated to be on the order of ~0.01–0.1 eV per atom, comparable to thermal and elastic energy terms.

Summary

These energetic contributions collectively define an energetic corridor of approximately 0.02–0.1 eV per atom. This corridor governs quasi-reversible structural rearrangements and defect redistribution during annealing at 450 °C, while remaining far below the Ta–O bond rupture energy, thereby preventing chemical degradation of the dielectric.

Appendix B. Estimation of Equivalent Strength Level

The equivalent strength level listed in Table X represents a theoretical estimate of the ideal lattice strength rather than a measured macroscopic property. It was obtained by converting the Ta–O bond energy into an equivalent stress using an atomic-scale energy density approach.

The estimation assumes that the stress required to break an interatomic bond is proportional to the bond energy divided by a characteristic atomic volume:

σequiv ≈ Ebond / Vchar

For tantalum pentoxide, the Ta–O interatomic distance is approximately 0.19–0.21 nm. Accordingly, the characteristic volume associated with one bond is approximated as Vchar≈ (0.2nm) ³ ≈ 8 × 10⁻³⁰ m³. The Ta–O bond energy is taken as 4–5 eV for amorphous Ta₂O₅ and 7–8 eV for crystalline Ta₂O₅, using the conversion 1 eV = 1.602 × 10⁻¹⁹ J.

This yields equivalent stress levels on the order of 10¹¹ Pa. For comparison with mechanical property data, the stresses were converted to kg/mm² using 1 kg/mm² = 9.81 × 10⁶ Pa, resulting in values of approximately 1000–1200 kg/mm² for amorphous Ta₂O₅ and 1700–1900 kg/mm² for crystalline Ta₂O₅.

The reported values should be regarded as theoretical upper-bound estimates based on interatomic bonding and are intended for comparative analysis.

References

- [1] V.Azbel https://passive-components.eu/mechano-chemical-model-of-sintered-tantalum-capacitor-pellets

- [2] V. Azbel https://passive-components.eu/optimize-tantalum-capacitor-performance-by-modeling-of-the-anode-structure/

- [3] V. Azbel: Structural Interpretation of Reliability in Tantalum Capacitor Anodes