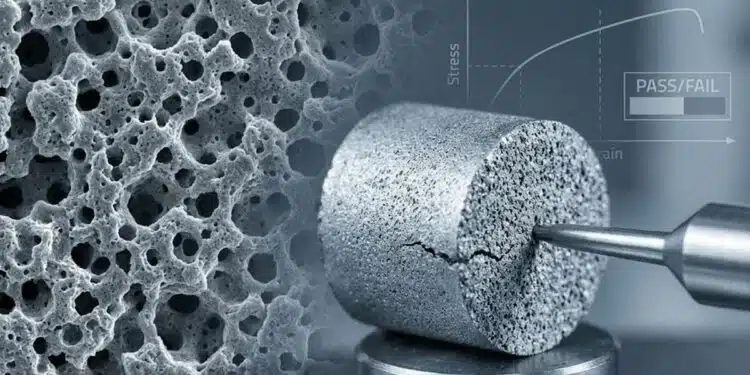

This article by Vladimir Azbel, an independent consultant on tantalum capacitors, discusses a mechanical testing method for distinguishing load-bearing necks from oxide-dominated regions in porous tantalum anode pellets used in tantalum capacitors. This method aims to predict the features of tantalum capacitors to enhance their quality, reliability and yield in manufacturing process.

Key Takeaways

- Mechanical testing can distinguish between load-bearing necks and oxide-dominated regions in porous tantalum anode pellets, improving tantalum capacitor quality.

- Current industrial methods primarily use shrinkage measurements, which fail to accurately reflect critical parameters like neck size and porosity.

- The study introduces a deoxidation (Deox) test that separates oxygen-related contributions from metallic neck strength, allowing for precise analysis of neck size and safety margins.

- The ‘30% Rule’ ensures that the cross-sectional area of tantalum necks does not decrease by more than 30% during formation, crucial for preventing thermal runaway.

- Overall, mechanical testing serves as a reliable process benchmark for sintered tantalum pellets, enhancing quality control and reliability in manufacturing.

The quality of a sintered tantalum pellet largely determines the performance and reliability of the final capacitor anode and thus the whole tantalum capacitor. In industrial practice, pellet quality is still primarily assessed by shrinkage measurements, which provide only indirect information and do not accurately reflect critical structural parameters, such as neck size, porosity, and internal stress level. These parameters directly control the allowable forming voltage, achievable capacitance, and the stability of direct leakage current (DCL).

In this work, mechanical testing is proposed as a virtual structural probe for characterizing sintered porous tantalum pellets. Analysis of the stress–strain response enables extraction of key mechanical parameters, including the yield strength (Ay), shear modulus (G), and strain hardening coefficient (K). These quantities provide direct insight into the load-bearing structure of the pellet and allow assessment of the characteristic neck size, porosity, and internal stress state.

A critical role in the mechanical response of sintered pellets is played by tantalum oxide phases, which inevitably form during sintering. Their influence is most pronounced in the neck regions, where oxide-rich layers generate local stresses and increase the susceptibility to defects in the amorphous Ta₂O₅ dielectric formed during anodic oxidation. As a result, yield strength Ay reflects not only the geometrical strength of metallic necks but also the contribution of oxygen-related oxide phases.

The present study demonstrates that Ay can be experimentally decomposed into independent geometrical and chemical contributions using a deoxidation (Deox) test, while the strain hardening coefficient K remains primarily sensitive to geometry. This separation enables estimation of the true neck size and provides a quantitative criterion for evaluating the safety margin of the forming process. The proposed approach allows rapid discrimination between acceptable and defective pellet batches and offers a physically grounded tool for process control and reliability improvement of porous tantalum anodes.

1. INTRODUCTION

The quality of a sintered tantalum pellet critically determines the performance and reliability of the final tantalum capacitor anode. Despite this, industrial quality control of sintered pellets is still predominantly based on shrinkage measurements, which provide only indirect information and do not reflect the acceptability of several structurally critical parameters. In particular, shrinkage does not allow reliable assessment of the neck size between particles, which defines the maximum allowable forming voltage; the porosity, which governs the achievable capacitance; or the level of internal stresses, which strongly affects the stability of direct current leakage (DCL).

In the present work, an alternative approach is proposed, in which mechanical testing of sintered tantalum pellets is employed as a “virtual structural probe”. By analyzing the stress–strain curve, key mechanical parameters such as the yield strength (Ay), shear modulus (G), and strain hardening coefficient (K) can be extracted. These parameters provide direct, physically meaningful insight into the underlying structural state of the porous pellet.

A particularly important role in shaping the local structure is played by crystalline tantalum oxides, which are an unavoidable byproduct of the sintering process. Their influence is most pronounced in the neck regions, where oxide phases tend to concentrate near the surface and generate high local stresses. The presence of oxide-rich regions significantly increases the risk of defect formation in the amorphous Ta₂O₅ dielectric film grown on the neck surface during anodic forming.

From an engineering perspective, the yield strength (Ay) serves as a virtual indicator of the mechanical and chemical state of the necks. However, this study demonstrates that Ay is not a single intrinsic parameter but represents the sum of two independent contributions: the mechanical strength of the metallic necks (geometry) and the strengthening induced by oxide phases (chemistry). We introduce a deoxidation-based (Deox) methodology to separate these contributions, enabling direct estimation of the true neck size and providing a quantitative criterion for assessing the safety margin of the forming process.

2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

2.1 Decomposition of Yield Strength The fundamental thesis of this work is that the effective yield strength of a porous tantalum anode, σeff, is cumulative. It can be expressed as the sum of independent contributions:

σeff (d, cO) = σ₀ + K·d⁻ⁿ + B·√cO (1)

Where:

- σ₀ represents the contribution of oxygen-free tantalum without size effects.

- K·d⁻ⁿ represents the size-dependent strengthening term (where d is the neck diameter).

- B·√cO accounts for the strengthening induced by interstitial oxygen and oxide-related species.

2.2 The Deoxidation Condition At zero oxygen concentration (cO = 0), Equation (1) reduces to the purely geometric strength:

σeff (d, 0) = σ₀ + K·d⁻ⁿ (2)

Thus, the effective yield strength corresponding to oxygen-free tantalum necks can be obtained by extrapolating experimental data:

σeff (d, 0) = σeff (d, cO) − B·√cO (3)

This extrapolation allows the yield strength of the metallic scaffold to be determined without the need to fabricate chemically pure material, provided the geometric parameters remain unchanged during deoxidation.

3. METHODOLOGY: THE “TRUTH MOMENT” (DEOX TEST)

To resolve the true structure, we utilize a Deoxidation (Deox) treatment. This process removes the oxygen contribution (σoxide → 0) without altering the neck topology. The yield strength measured after Deox reflects only the metallic skeleton:

σdeox ≈ σneck (3)

3.1 Estimation of Neck Size from Oxygen-Corrected Yield Strength After removing the oxygen contribution using Eq. (3), the remaining yield strength reflects purely the geometrical characteristics of the load-bearing network. The oxygen-corrected yield strength can be related to the characteristic neck size using a geometrical scaling relation based on the Minimum Solid Area (MSA) model:

σdeox = b · σ0 · (X / D)² (4)

Solving Eq. (4) for the neck size yields:

X = D · √(σdeox / (b · σ0)) (5)

Where:

- σ₀ is the yield strength of solid, oxygen-free tantalum (~19 kg/mm²).

- X is the characteristic neck size.

- D is the characteristic pore spacing (or particle size).

- b is an effective coefficient accounting for network topology and stress heterogeneity.

This approach enables a physically consistent estimation of neck size directly from mechanical measurements and avoids the systematic overestimation that would arise if oxygen-induced strengthening were not removed.

3.2. Model Parameterization and Critical Threshold

“The rationale for the critical relative neck size (X/D) threshold of 30% is based on a combined approach that integrates empirical production data with theoretical modeling:

1. We conducted a retrospective analysis of production statistics for anode batches that successfully passed qualification. The key known parameters were the specific powder type and the formation voltage.

2. The geometry of the porous structure (specifically, the sintering neck radius) was estimated using standard shrinkage curves provided by the powder manufacturer (Starck).

3. By applying our previously developed methodology for calculating thermal fields within the anode [1,2], we correlated the estimated neck size with the applied formation voltage.

This analysis revealed a distinct cut-off value for the relative neck size at approximately 0.30 (or 30%); below this threshold, the probability of thermal breakdown during the formation process increases significantly.”

4. ENGINEERING APPLICATION: THE 30% SAFETY RULE

The critical danger in High-CV anodes is Thermal Runaway during anodization. As the anodic film grows, it consumes metallic tantalum. If the initial neck (X) is too thin, the conductive cross-section may reduce to a critical level, causing local current density to spike and leading to defect formation.

We establish the “30% Rule”: The cross-sectional area of the metallic neck must not decrease by more than 30% during the formation process.

Risk Calculation Example: Consider a 150,000 CV/g powder:

- Target Formation Voltage: 16 V

- Metal Consumption: ≈ 29 nm (total diameter reduction).

- Critical Threshold: To satisfy the 30% rule, the initial metallic neck X must be ≥ 100–110 nm.

Using Equation (5), we can translate this physical limit into a mechanical threshold. If the mechanical test after Deox yields σdeox < 0.5–0.8 kg/mm², the batch is classified as High Risk, regardless of how strong it appeared before deoxidation.

5. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

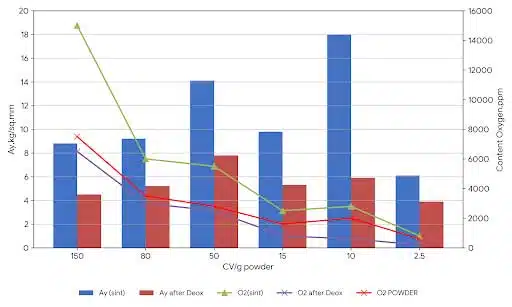

5.1 Experimental Evidence of Oxide-Dominated Strength The experimental results, summarized in Figure 1, reveal a fundamental difference in mechanical behavior across the capacitance range. For Low-CV powders (e.g., 2.5k), the yield strength remains stable before and after deoxidation (Ay drops minimally), indicating that the load-bearing capacity is provided primarily by massive metallic necks. In sharp contrast, High-CV powders (e.g., 150k) exhibit a dramatic collapse in yield strength after deoxidation (from ~9 to ~4.5 kg/mm²), which correlates perfectly with the removal of excess oxygen.

An important experimental observation of the present study is the quantitative relationship between the reduction of yield strength after deoxidation and the corresponding decrease in oxygen concentration.

For all investigated neck sizes, the ratio of yield strengths measured after and before deoxidation was found to be: σafter / σbefore ≈ 0.53–0.56

At the same time, the ratio of square roots of oxygen concentrations satisfies: √(cOafter) / √(cObefore) ≈ 0.58–0.69

Considering experimental scatter, possible radial oxygen gradients across the neck cross-section, and the statistical nature of yielding in a porous network, the agreement between these ratios is remarkably good.

Since deoxidation does not alter porosity or neck geometry, this experimental result indicates that the observed change in yield strength is dominated by the oxygen contribution. The close correspondence between the yield strength ratio and the square-root oxygen ratio demonstrates that oxygen affects the yielding of porous tantalum primarily through strengthening of the neck material, rather than through structural changes of the porous network.

From an engineering perspective, this experimentally established relationship provides a practical basis for correcting yield strength for oxygen content and for extrapolating mechanical properties to oxygen-free conditions.

5.2 Physical Interpretation of the √cO Dependence Upon cooling from the sintering temperature, the solubility limit of oxygen in tantalum is crossed at approximately 1100 °C, leading to the precipitation of oxide-related phases within the neck material. Due to the high Pilling–Bedworth ratio of Ta₂O₅ (~2.47), oxide formation is accompanied by significant volumetric expansion, generating local internal stress fields in the constrained neck geometry.

These stresses, together with strong lattice curvature and stress gradients inherent to the neck regions, are expected to promote stress-assisted oxygen redistribution and segregation toward the neck surface. As a result, the load-bearing necks may develop a heterogeneous radial structure consisting of a relatively ductile metallic tantalum core surrounded by an oxide-rich, mechanically brittle shell.

Such a composite-like neck configuration provides a physically consistent explanation for the experimentally observed √cO scaling of yield strength and for the dominance of oxygen-related strengthening despite saturation of the tantalum matrix. Importantly, this mechanism affects the local mechanical response of the neck material without altering the overall neck geometry or porosity, thereby justifying the subsequent separation of oxygen-related and geometrical contributions in the engineering model.

5.3 Mechanical Testing as a Process Benchmark Limitations of Conventional Testing: Direct electrical characterization (capacitance, DCL) of sintered anodes is impossible before dielectric formation, as the pellet acts solely as a porous conductor. The industrial standard ‘Wet Test’ requires an additional anodization step, which masks the specific effects of sintering by superimposing the quality of the dielectric layer onto the properties of the sintered neck. Consequently, a rejected batch at the wet test stage represents a significant loss of processing time and resources.

Use of Mechanical Properties as a Process Benchmark: The proposed mechanical testing approach provides an immediate quality benchmark for the as-sintered state, allowing for the detection of thermal processing errors (e.g., oxidation, over-sintering) before any further value is added to the product. The established relationship between yield strength and oxide content suggests that mechanical testing can serve as a rapid and sensitive benchmark for the sintering process. Since the excess oxygen content is directly linked to non-optimal processing parameters—such as peak sintering temperature, cooling rates, or passivation protocols—deviations in yield strength from a standard baseline (benchmark) can effectively detect process irregularities.

Unlike electrical characterization, which requires further processing steps (anodization), mechanical testing of sintered anodes offers an immediate feedback loop to optimize thermal profiles and minimize contamination. The comparison of these approaches is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Comparison between conventional electrical characterization (“Wet Test”) and the proposed mechanical testing approach for sintered tantalum anodes.

| Feature | Conventional “Wet” Test (Electrical) | Proposed Mechanical Test |

|---|---|---|

| Testing Stage | Post-Anodization (requires dielectric layer) | As-Sintered (immediately after sintering) |

| Physical State | Metal-Dielectric-Electrolyte system | Porous Metallic Sintered Body |

| Parameter Sensitivity | Convoluted (mix of sintering quality and dielectric integrity) | Isolated (sintering quality, neck size, and oxide content) |

| Process Feedback | Delayed (requires additional processing steps) | Immediate (real-time process control) |

| Resource Efficiency | Low (resources wasted on processing potentially defective batches) | High (early detection of thermal processing errors) |

6. CONCLUSION

The introduction of mechanical testing with an obligatory Deox phase transforms quality control from statistical data gathering into physical structural analysis.

- Decomposition Principle: We validated that the yield strength can be decomposed into independent size-dependent (geometric) and oxygen-dependent (impurity) contributions. This allows for separating the intrinsic strength of the metallic skeleton from the parasitic strengthening caused by interstitial oxygen.

- Quantification Method: Extrapolation to zero oxygen concentration allows for determining the “true” load-bearing capacity of the necks. The derived formulas enable the direct calculation of the characteristic neck diameter (X) solely from mechanical data, bypassing the need for complex destructive imaging.

- Safety Criterion (“The 30% Rule”): Analysis of historical production data established a deterministic pass/fail criterion. Maintaining the relative neck size (X/D) above 30% guarantees the structural integrity required to prevent thermal overload and breakdown during formation.

This framework empowers manufacturers to optimize sintering profiles to achieve the delicate balance: maximizing capacitance while rigorously guaranteeing safety margins based on physical parameters rather than empirical guesswork.

References

- [1] Helmut Haas, Magnesium Vapour-Reduced Tantalum Powders with Very High Capacitances, CARTS Europe 2004: 18th Annual Passive Components Conference, October 18-21, 2004

- [2] V.Azbel, Digital Twin of a Tantalum Capacitor Anode: From Powder to Formation, passive-components,8.12.2025